by Ronald Brownstein

Mitt Romney could run as well among whites as any Republican presidential challenger in the history of polling—and still lose. That equation carries threats for both parties.

Mitt Romney could run as well among whites as any Republican presidential challenger in the history of polling—and still lose. That equation carries threats for both parties.

For Republicans, that prospect crystallizes the danger of an electoral strategy that has left the party almost entirely dependent on white voters, even as their numbers decline. For Democrats, the possibility that President Obama could face landslide rejection from the white majority, even if he survives, underscores the party’s inability to hold support among whites while implementing its agenda—a trend that traces back to Lyndon B. Johnson.

Polls so far suggest that the election could divide the nation along racial lines even more starkly in 2012 than in 2008. Four years ago, Obama won a combined 80 percent among all nonwhite voters—including African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and others. Almost all surveys this year show him positioned to equal, or slightly exceed, that dominant performance.

In 2008, Obama won only 43 percent of white voters to John McCain’s 55 percent. Most surveys this year suggest Obama will struggle to match even that modest showing among whites; in recent surveys, the president typically draws about 40 percent of them—usually slightly less, sometimes slightly more. That means Romney will likely exceed McCain’s white showing, and could even approach (or potentially pass) 60 percent with that group of voters.

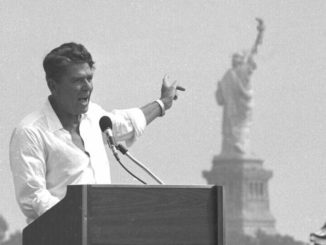

If Romney nears that level, he will match the best performances among whites ever for a Republican presidential challenger. Polls at the time found that whites gave from 56 percent to 61 percent of their votes to Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, Ronald Reagan in 1980, and George H.W. Bush in 1988.

For each of those men, those crushing margins among whites translated into an electoral landslide. Each won at least 426 Electoral College votes and cruised in the popular vote.

Yet this year, Romney could win as much as 60 percent of the white vote (or, amazingly, even slightly more) and still lose. The reason is the electorate’s changing composition. When Reagan was first elected in 1980, whites cast about 90 percent of the votes; even in Bush’s 1988 victory, whites represented 85 percent of all votes and minorities just 15 percent.

But by 2008, after two decades of steady growth, minorities cast 26 percent of all votes. One recent analysis found they represent 29 percent of eligible voters for 2012. Even if the minority vote share remains flat at 26 percent, should Obama hold his 80 percent of it, he can win a national majority with slightly less than 40 percent of whites.

The fact that Romney could roughly equal the towering performances of Eisenhower, Reagan, and Bush among whites and still fall short ought to alert Republicans about the dangers of an electoral strategy so dependent on those voters alone. “If Republicans are going to be competitive at the presidential level over the next 10-20 years they have to do better among nonwhite voters, especially Asians and Hispanics,” says GOP pollster Whit Ayres. “[If you] basically win a landslide among whites and still lose, the handwriting is on the wall.”

But because the GOP now relies so heavily on support from the white voters most uneasy about demographic change (primarily older and blue-collar whites), it has almost completely lost the capacity to court Hispanics or other minorities—as Romney demonstrated during the primaries by pummeling any opponent who deviated from conservative orthodoxy on immigration issues. A dominating Romney showing among whites that produces at best a narrow win, and at worst a defeat, would reveal that insular approach as a dead end for the GOP—though more Republicans are likely to heed the warning after a defeat than a victory.

But because the GOP now relies so heavily on support from the white voters most uneasy about demographic change (primarily older and blue-collar whites), it has almost completely lost the capacity to court Hispanics or other minorities—as Romney demonstrated during the primaries by pummeling any opponent who deviated from conservative orthodoxy on immigration issues. A dominating Romney showing among whites that produces at best a narrow win, and at worst a defeat, would reveal that insular approach as a dead end for the GOP—though more Republicans are likely to heed the warning after a defeat than a victory.

Conversely, while the growing minority population is bolstering Democrats, it shouldn’t obscure the implications of a white stampede away from Obama. Even if Obama survives, Democrats are unlikely to build an enduring majority coalition—particularly in Congress—if they cannot sustain support among whites while implementing their agenda. And since the days of LBJ’s Great Society, they simply have not proven they can do that.

Since 1964, Democrats have enjoyed unified control of Congress and the White House for full four-year terms under Johnson and Jimmy Carter and for the first two years during the presidencies of Bill Clinton and Obama. During each of those periods, polls showed the party hemorrhaged support among whites; over the first two years of the LBJ, Clinton, and Obama presidencies, Democratic House candidates saw their vote share among whites collapse each time by nearly 10 percentage points. Carter won only about one-third of whites in his reelection campaign.

The inability to hold whites while enjoying a free hand to implement their program ought to send Democrats a clear signal. If the party cannot formulate a vision for activist government that retains white support, it is unlikely to control Washington for any lasting period. “It’s an unsustainable political model that can write off [about] 60 percent of white America,” notes veteran Democratic strategist Bill Galston. Both sides have reasons for anxiety about the racial chasm looming in November.

This article appeared on the National Journal on 8/10/12