Elijah Calderon, after a yearlong training program at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College, is poised to earn about $105,000 annually as a power lineman. Once he becomes a journeyman in three to four years, he stands to make about $165,000 — and potentially much more with overtime.

He had to let go of his high school dream of attending a four-year university because of family finances. But his chosen field in the community college system will propel him to the top 5% of wage earners among recent California college graduates — outearning many who attended the most prestigious universities in the state and the nation.

A Stanford University student graduating with a bachelor’s degree in political science makes a median annual income of $75,500 four years after graduation. A UC Berkeley sociology major earns about $64,000 at that four-year snapshotand a UCLA graduate in history, about $47,900, according to a new analysis of federal data by the HEA Group, a research and consulting agency focused on college access.

As millions of high school and college students graduate this month to pursue higher education or launch newly minted careers, the data highlight the powerful role that their majors play in determining post-graduate earnings regardless of the prestige of the institutions they attend. The analysis comes amid growing scrutiny over the value of college degrees — and whether higher education is worth the rising costs.

“Overwhelmingly, the answer is still yes, college is worth it,” said Michael Itzkowitz, president of the HEA Group. “However, students and families should choose the institution they go to and the major they pursue wisely when making one of the largest financial decisions they’ll ever make.”

Majors matter

While UC and top private campuses are flooded with applications, students’ post-graduation earnings can be as much — or more — with degrees from the more accessible California State University or California Community Colleges, depending on the field, data analyzing California institutions showed.

Among computer engineering majors, for instance, San Jose State graduates earn a median$127,047 four years after graduation. That’s nearly the same as UCLA’s $128,131 and more than USC’s $115,102, as well as seven other UC campuses that offer the major, which combines software development with hardware design. Cal State graduates in that field from Chico, Long Beach, Fresno, Fullerton, Sacramento, San Francisco and San Luis Obispo earn more than $90,000 annually.

“It really pays to look at outcomes and not be blinded by the brand name,” said Martin Van Der Werf of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. “The best brand name doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to result in the highest life earnings.”

Itzkowitz said Cal State is a particularly good deal. The CSU annual base tuition is only $5,742, compared with $13,752 at UC and $66,640 at USC, although such variables as financial aid and housing costs affect the actual out-of-pocket expenses. Even if Cal State increases tuition, which some officials are proposing to address a $1.5-billion budget gap, the price would still be thousands lower than UC.

“The CSU system itself has really been shown as a pillar of producing economic mobility for students,” he said. “It enrolls a more economically diverse student body. And it also has been shown to produce strong economic outcomes for lower and moderate-income students. They’re really at the top of the list of affordability and outcomes.”

A hard look at college outcomes

Amid fears about college costs and loan debt burdens, more students and families are looking to higher education for clear career dividends rather than a general quest for intellectual enrichment, Van Der Werf said. That trend has accelerated since higher education costs began to climb after the 2008 recession, he added.

At UC Berkeley, for instance, computer science is now the most popular major, rocketing from seventh place in 2014-15, while psychology and English have fallen. The campus recently unveiled a new College of Computing, Data Science and Society — its first new college in more than 50 years — to respond to enormous demand from students and faculty. Data science has become the university’s third-most-popular major just five years after it was established.

Colleges are under growing scrutiny by federal and state officials for the returns they deliver. Comprehensive public data aboutthe mediansalaries earned by graduates in specific majors at specific universities became available beginning in 2015 with the launch of the federal College Scorecard — an accountability effort by the Obama administration that accelerated under President Trump.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom has increasingly tied education funding to career training in specific high-demand fields — healthcare, education, climate and technology. Newsom and the state’s three public systems of higher education have agreed on goals to educate more graduates in those fields, and the governor has proposed or invested hundreds of millions of dollars in career-focused programs for high school students. Some of that funding, however, could be cut during negotiations with the Legislature to close a $31.5-billion budget deficit.

Newsom is aiming to foster closer connections between educators and employers to meet state workforce needs and create student pipelines to meaningful careers — an approach used in Singapore, said Ben Chida, who leads Newsom’s educational agenda as chief deputy cabinet secretary.

“The core question facing education and our young people today is how do we help students find and make meaning in their lives?” Chida said. “It oftentimes involves having a career … that leads to both personal and community prosperity.”

Other states are also linking career training to higher education funding. A new Texas law will tie the majority of state community college funding to performance-based measures, including postgraduate earnings and the number of credentials awarded in high-demand fields.

Such developments highlight long-standing questions over whether universities should cater to the market trends of the day or retain the full breadth of educational offerings, including liberal arts. As workforce demand in computer science, engineering and healthcare fields explodes, some institutions are making more room for these majors by cutting less popular programs — often targeting the humanities.

In Virginia, Marymount University trustees created an uproar in February by unanimously voting to ax nine liberal arts majors, including art, economics, English, history, mathematics, philosophy, secondary education, sociology, theology and religious studies. The majors will be dropped for new students beginning this fall but the classes will still be offered, a spokesman said.

A 2017 UC report pushed back on efforts to diminish the humanities and favor fields thought to lead to high-paying jobs. The report, commissioned by the UC Office of the President, called such policies “shortsighted” and “unnecessary market intervention” because states had a poor track record of predicting future workforce needs and fail to consider the speed at which technology is changing the nature of work.

The report noted that automation was expected to displace as many as 40% of U.S. jobs — and the rise of generative AI today could affect as many as 300 million jobs globally, a recent Goldman Sachs analysis concluded.

In contrast, the report said, the study of humanities builds such evergreen skills as communication, teamwork and critical thinking. It noted that humanities graduates nationally earn on average “significantly” more than the national median income and the pay gap with other fields narrows over time. But even if colleges trim liberal arts majors, they will retain the classes as part of their broad core curriculum requirements for every student — a hallmark of U.S. higher education.

The California picture

The data compiled from more than 36,000 programs at 4,441 public and private institutions nationwide reflected median earnings for the Class of 2016 four years later, adjusted for inflation. It marks a single point in time; wages grow after that at different rates — those for liberal arts majors, for instance, increase more quickly than others although they never catch up to science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields.

Overall, computer science, engineering and health sciences programs provide the highest returns on college investments.

In California, where 2,700 programs at 386 institutions were analyzed, about 42% of majors delivered median earnings between $40,000 and $59,999. They included a range of majors, including business administration, biology, communications, mathematics and criminal justice.

Business administration drew the largest number of students. Median annual income for graduates of four-year programs varied widely — from $123,780 for UC Berkeley to $28,602 for La Sierra University, a private campus in Riverside.

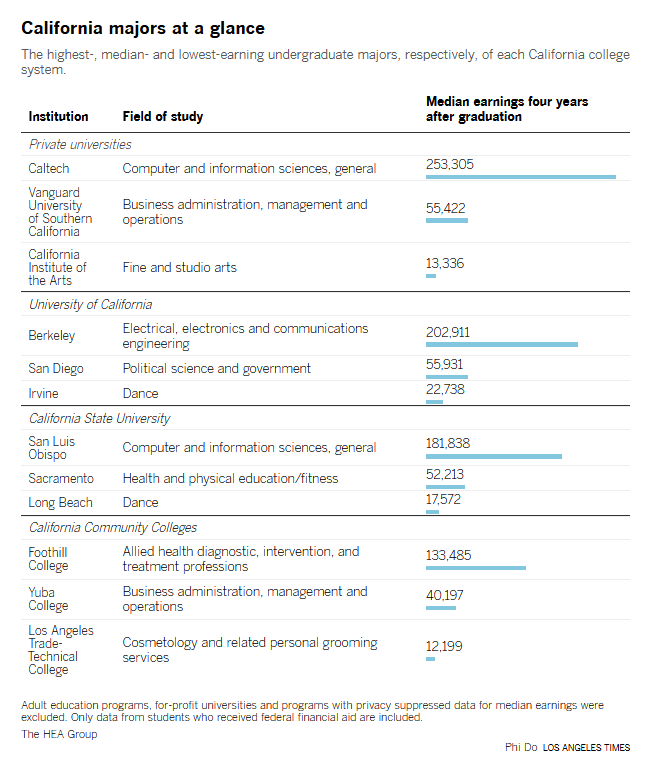

The highest-paid graduates are Caltech computer and information sciences majors, who earn $253,305.

Health field graduates also command high salaries — including those with community college degrees. Registered nursing graduates with two-year degrees from Sacramento City College earn $123,056 annually, more than those with bachelor’s degrees in nursing at UCLA and UC Irvine. Experts say that geography can play a role, with wages often higher in the Bay Area. Most community college registered nursing programs deliver median earnings of more than $90,000 annually, the data show.

In the San Jose area, Foothill College graduates of two-year allied health programs — including dental hygiene, diagnostic medical sonography and respiratory therapy — earn a median salary of $133,485. As a San Jose high school student, Emily Kong was interested in interior design but a career match quiz indicated dental hygiene would be a good fit — and offered far higher pay. She enrolled in Foothill, bypassing the nerve-wracking college admissions process that agonized her friends; temporary agencies are guaranteeing dental hygienists at least $550 a day, she said.

Registered nursing graduates from three L.A. County community colleges — Los Angeles Southwest, Los Angeles City and Cerritos — all make $100,000 or more four years after graduation. In other fields, graduates of two-year programs in fire protection at Santa Ana College and electrical and power transmission installation at L.A. Trade-Tech earn more than $95,000 annually.

In contrast, the lowest-paid recipients of bachelor’s degrees in California tend to be those in music and the arts. Graduates in drama, theater and stagecraft from USC, UC Berkeley and UC Irvine make less than $30,000 annually, according to the federal data.

But many students still pursue fields they know won’t make them rich but fire their passions. At UC Berkeley, even as demand skyrockets for data and computer science, interest has also surged in music, art practice and film and media — which are recording double-digit increases in students majoring in those fields.

Wilson Wang, a fourth-year Berkeley student from China, started out as a bioengineering major on a premed track. But as he realized the difficulties for international students to get into U.S. medical schools, he began pondering options — and found a new passion after taking a class about Chinese film auteurs. He switched to a film and media major — even though his parents, both doctors, “freaked out for a second.” They’ve come around to support him.

Wang is picking up a second major in environmental economics and policy just in case film doesn’t pay the bills. But he feels that the creativity and critical thinking he’s developing through his film major will prove valuable to a future employer. “It’s a cliche, but I’m following my heart,” he said.

Jacob Li Rosenberg, a Berkeley undergraduate, started off with architecture, a major he believed would be useful in the job market. But he soon became captivated by art classes and the creative freedom they offered; he changed his majors to art practice and sociology. The multidisciplinary artist created an installation last year featuring sewn textiles, photography, interviews and sculptures that honored his Chinese and Jewish heritages, along with Native people and immigrants.

Rosenberg figures he’ll be able to live on $40,000 a year and is prepared to cobble together grants, teaching gigs, art sales and whatever else it takes to make his budget. He said art offers rich and intangible rewards.

“I find a lot of happiness and joy when I can use my art to support my communities, my friends, my families, and really do meaningful work,” he said. “It’s a very cliche thing, but money doesn’t buy happiness.”

Calderon, meanwhile, doesn’t regret his decision to drop plans for a four-year degree in favor of a trade as a pole lineman. His education was free, thanks to federal and state financial aid. The work, which involves building and maintaining electrical power systems often atop 35-foot poles, has given him pride of accomplishment. He’s gotten in shape, mastered marketable skills and is set to begin a path to financial prosperity.

“There’s more than just going through a four-year,” he said. “Be a little more open to trade school. Give it a chance.”

Teresa Watanabe covers education for the Los Angeles Times.