The growing efforts by red states to seize authority over law enforcement in blue cities is drawing energy from the convergence of two powerful trends.

by

Republican-controlled state governments are opening an explosive new front in their decadelong drive to exert more control over the decisions – and decision makers – in Democratic-run cities and counties.

From Florida and Mississippi to Georgia, Texas and Missouri, an array of red states are taking aggressive new steps to seize authority over local prosecutors, city policing policies, or both. These range from Georgia legislation that would establish a new statewide commission to discipline or remove local prosecutors, to a Texas bill allowing the state to take control of prosecuting election fraud cases, to moves by Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and Missouri Republican Attorney General Andrew Bailey to dismiss from office elected county prosecutors who are Democrats, and a Mississippi bill that would allow a state takeover of policing in the capital city of Jackson.

“If left unchecked, local jurisdictions in states with conservative legislatures whose political majority does not match their own may find themselves subject to commandeering on an unprecedented scale,” said Janai Nelson, the president and director-counsel of the Legal Defense Fund, a leading civil rights group.

The growing efforts by red states to seize authority over law enforcement in blue cities is drawing energy from the convergence of two powerful trends.

One is the increased tendency of red states to override the decisions of those blue metros on a wide array of issues – on everything from minimum wage and family leave laws to environmental regulations, mask requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic, and even recycling policies for plastic bags. The other is the intensifying political struggle over crime that has produced an intense pushback against the demands for criminal justice reform that emerged in the nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

“A lot of this criminal justice reform preemption is in direct response to the Black Lives Matter movement,” said Marissa Roy, legal team lead for Local Solutions Support Center, a group opposing the broad range of state preemption efforts.

Many of the red state moves to preempt local district attorneys have targeted the so-called “progressive prosecutors” elected in many large cities over recent years. But there is also an unmistakable racial dimension to these confrontations: In many instances, state-level Republicans elected primarily with the support of White, non-urban voters are looking to seize power from, or remove from office, Black or Hispanic local officials elected by largely non-White urban and suburban voters.

“There’s a strong hint of discrimination because most of the prosecutors they are coming after are black women, or [other] people of color who don’t line up with a hard-core lock ‘em up philosophy,” said Gerald Griggs, a criminal defense attorney and president of the NAACP in Georgia.

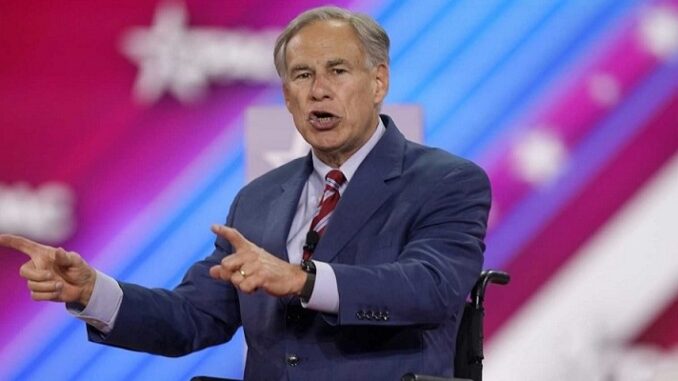

With so many forces converging, all signs suggest the conservative drive to constrain liberal local prosecutors and assert more control over policing in heavily Democratic big cities has not nearly peaked. Indeed, former President Donald Trump has already pledged that if returned to the White House he will push a suite of aggressive federal policies to counter what he has called “radical left” and even “Marxist” prosecutors. In his dark, rambling speech earlier this month at CPAC, Trump declared that if reelected he would direct the Justice Department to launch civil rights investigations against the progressive prosecutors “to make them pay for their illegal race-based enforcement of the law.”

The Republican governors and state legislators pushing these preemption proposals mostly argue that they are necessary to combat high crime rates in municipalities under Democratic control. “Action must be taken to ensure that district attorneys are held accountable for their actions and carry out their duties by enforcing the laws we have on our books,” Texas GOP state Sen. Tan Parker said when introducing a bill earlier this year that would allow the state’s attorney general to remove local prosecutors.

But the push is also being fueled by the resistance from some prosecutors in the blue counties of red states to enforce the wave of new socially conservative bills that have burned through those states since 2020, including bans on abortion and gender affirming surgery for minors. Andrew Warren, the elected Democratic state attorney in Hillsborough County, Florida, who DeSantis removed from office last year, for instance, had indicated he would not enforce the 15 week abortion ban the governor has signed into law.

“For progressive prosecutors this is a politically self-inflicted wound,” said Thomas Hogan, a former federal prosecutor and elected Republican district attorney in Chester County outside Philadelphia, who has emerged as a leading critic of the liberal district attorneys. “When you … stand up on the tallest building in your jurisdiction and holler at the legislature that you are not going to follow their law, somebody is going to pay attention,” he added. “When you do something like that you are basically waving a red cape in front of a bull.”

In the states, these battles have unfolded almost entirely along party lines, with Republicans pushing these initiatives and Democrats resisting them. Yet national Democrats may have muddled their message against the preemption of local criminal justice authority when so many of them in Congress, as well as President Joe Biden, joined the recent Republican-led congressional effort to overturn a sweeping criminal justice reform approved by the Washington, DC, city council.

Though the congressional vote raised somewhat different issues than the state fights, the decision by so many Democrats to endorse the override effort underscores how much momentum elevated public concern about safety and disorder is generating for tough-on-crime policies. That message has been reinforced by the defeat of Mayor Lori Lightfoot in Chicago’s recent mayoral primary, last year’s recall of San Francisco’s reform-oriented district attorney Chesa Boudin, and the election of Eric Adams behind a crackdown platform in New York City.

The state moves to preempt local prosecutorial authority has directly followed the increased electoral success of so called “progressive prosecutors” committed to reducing incarceration rates, confronting racial inequities in the criminal justice system and more aggressively prosecuting police misconduct. The first of the “progressive prosecutors” were elected in the mid-2010s, after the racial justice protests flowing out of Ferguson, Missouri, but the movement really accelerated after the nationwide uprising over the murder of George Floyd in 2020.

Today, there are between 50-60 prosecutors considered part of the movement – including in major jurisdictions such as Manhattan, Brooklyn, Los Angeles, Chicago and Philadelphia – with jurisdiction over populations equaling about one-fifth of the US total, said Nicholas Turner, president of the Vera Institute of Justice, a group that supports criminal justice reform. And while San Francisco last year recalled Boudin, Turner pointed out that virtually all the progressive district attorneys who sought reelection have won it.

The push by Republican-controlled legislators to preempt more local authority over criminal justice enforcement began soon after these prosecutors took office. In 2019, the GOP-controlled legislature in Pennsylvania passed a bill to shift authority over prosecuting some gun possession offenses from Philadelphia’s liberal DA Larry Krasner to the state. In the 2021-2022 legislative session, Iowa, Tennessee and Utah also passed bills to constrain local prosecutors or to make it easier to force their removal, according to a recent compilation by the Local Solutions Support Center. Over those same two years, as cities faced growing demands from activists to shift funding from law enforcement to social services, Florida, Georgia, Texas and Missouri passed laws preventing local jurisdictions from reducing their police budgets.

As the LSSC argued in its recent survey of preemption, “After going unchallenged for centuries, prosecutorial discretion has come under fire only after local prosecutors have begun to use it to combat – rather than entrench – systemic racism.”

Efforts to supersede local control of law enforcement decisions in Democratic-leaning cities and counties are proliferating in red states again this year.

In Georgia, the Republican-controlled state House and Senate have each passed legislation that would establish a new statewide commission to investigate, discipline and remove local district attorneys. The bill, which has the strong support of Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, has raised eyebrows especially because it is advancing as the elected Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is investigating the attempts by Trump, as well as Georgia GOP officials, to overturn the result of the 2020 election there.

The Republican-controlled Texas legislature is considering seven different proposals to override or ease the removal of local prosecutors. Last week, the state’s powerful and deeply conservative Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick identified as one of his priority bills for the current legislative session a measure that would allow the state to remove any local prosecutor who “prohibits or materially limits the enforcement of any criminal offense.” Another bill would allow the state attorney general to appoint district attorneys from neighboring counties to prosecute cases of alleged election fraud if the local DA will not.

In Missouri, the state House of Representatives has approved legislation that would shift authority for prosecuting violent crimes from elected local prosecutors to a special prosecutor appointed by the governor once a county’s crime rate crosses a certain level. The House has also passed legislation that would shift operational control over the police department in St. Louis to the state. And last month, Bailey, the state’s Republican attorney general, began a legal process to force from office Kimberly Gardner, the St. Louis circuit attorney.

In Mississippi, the Republican-controlled state legislature is advancing legislation to expand state control over policing and the courts, and largely displace local authority, in Jackson, the predominantly Black capital city.

In Florida, beyond removing Warren, DeSantis’ office has also begun an investigation that may culminate in the removal of Monique Worrell, the elected Democratic state’s attorney in Orange County, centered on Orlando. DeSantis argues she mishandled the case of a 19-year-old man recently arrested for shooting three people in the city.

Taken together, these initiatives constitute an unprecedented challenge to the independence of local prosecutors, said Richard Briffault, a Columbia Law School professor who studies state preemption of local decisions. “This is a straightforward attack on a system we’ve had in place for hundreds of years: local elections of local prosecutors,” he said.

Some of those targeted by these efforts, such as Krasner and Warren, are White. But in most cases, these efforts target Black local officials in heavily minority jurisdictions, including the mayors of St. Louis and Jackson; the county attorneys in the counties centered on Atlanta, Orlando, and St. Louis are all Black women.

In testimony before a state legislative committee considering the Georgia bill, Willis noted the proposal has emerged only after the number of county prosecutors who are racial minorities has recently nearly tripled in Georgia, to the point where they now oversee a majority of the state’s population. “I’m tired and I’m just going to call it how I see it,” Willis told another group of legislators “I, quite frankly, think the legislation is racist. I don’t know what other thing to call it.” The Black mayors of St. Louis and Jackson Mississippi have made similar charges.

Hogan agreed the racial dimension of the conflict complicates the politics of the state efforts. But he believes those pushing preemption can rebut the charges of racism by pointing out that “the citizens of those cities and right now the folks who are suffering the most in the violence of those cities are the poor, minority citizens.” Hogan likened the state efforts to preempt prosecutors to the movement for mandatory minimum sentences and federal sentencing guidelines that emerged after the 1960s to constrain sentencing decisions by judges that critics considered too lenient.

Yet on balance, Hogan said he believes the red states are mistaken to seize control from local prosecutors and law enforcement as they are doing. Hogan argues that as in San Francisco’s recall of Boudin, voters fed up with crime and urban disorder will eventually reject the progressive prosecutor movement. That would provide a more lasting shift, he maintainrf, because state “attempts to jump in and cut off the democratic process” will leave open the question of whether the progressive policies would have succeeded if left in place. “People would be better off letting voters and reality make a correction here in the long run,” Hogan said.

Turner of the Vera institute, noting how many of the progressive prosecutors have won reelection, disputes the idea that their voters will reject the movement. But he also views the drive for more state control as “profoundly anti-democratic” since it involves state legislatures overriding the choices of local voters to set criminal justice priorities for their communities. Roy likewise pointed out that the progressive prosecutors did not engage in a “bait and switch” but rather were elected after explicitly promising the shifts in direction that they are executing. In that way, she said, the red state legislatures, “are directly subverting what local communities are asking for.”

Exacerbating this conflict is the fact that in many red states GOP control of legislatures and governorships is rooted in their dominance of exurban, small town and rural areas far from the urban centers that are the targets of these preemption efforts. Severe gerrymanders that dilute urban influence compounds the challenge for the population centers in many of the states pushing preemption agendas.

Trump has pledged to extend this preemption agenda to the national level. Beyond his call for Justice Department investigations of local prosecutors, Trump has said he will push legislation to authorize federal lawsuits against local district attorneys by anyone who claims they were harmed by their refusal to prosecute certain crimes. Perhaps most dramatically, Trump has repeatedly declared that in cities “where there has been a complete breakdown of public safety, I will send in federal assets including the national guard until law and order is restored,” as he put it in his recent speech to the CPAC convention.

The push to seize more authority over criminal justice comes after a decade in which red states have dramatically expanded their efforts to tighten their control over blue cities on almost every front. Few areas of governmental authority now appear beyond the reach of preemption demands. “If you go back into the mid 2010s, a lot of the preemption was driven by business-it had to do with workplace equity, living wage, family leave, medical leave, and maybe some pollution-oriented regulations,” said Briffault. “This stuff is all ideological now: crime, elections, schools.”

As the federal battle over the Washington, DC, criminal code reform showed, Republicans clearly feel they have the initiative in debates over crime, and Democrats are divided and ambivalent about how to respond. Against that backdrop, the safest prediction is that more Republican-controlled states will push to remove more authority over law enforcement and criminal justice decisions from big blue jurisdictions, most of them with large non-White populations. “We are in Georgia, we are in the South,” said Griggs, the Georgia NAACP president. “We saw what they did in the ’60s, in the ‘40s and ‘50s. So, there is no boundary.”

Ronald Brownstein is a CNN senior political analyst, regularly appearing across the network’s programming and special political coverage. Brownstein is Atlantic Media’s Editorial Director for Strategic Partnerships, in charge of long-term editorial strategy.

.