In a recent Los Angeles Times editorial, Stand for Children’s Jonah Edelman and the American Federation of Teachers’ Randi Weingarten blasted the private-school choice programs that the Trump Administration has strongly promoted. They built their case, in part, on the notion that public schools are “open to all,” while stating that private schools are not. But can public schools claim the high ground on admissions? Is every public school district really open to all?

In the words of football analyst Lee Corso: “Not so fast.” Consider Fordham’s home state of Ohio where, like most states, boundary lines have long determined public-school assignments. For many families, their “zoned” schools are fine and were very likely a driving force during the home-buying process. Other parents, however, might prefer to send their child to another district. They may want access to a specialized academic program or to ensure their kids attend a school that is nearer to their home than the one assigned to them, even if it means crossing a district boundary.

To offer parents more interdistrict opportunities, Ohio legislators enacted one of the nation’s first open enrollment laws in 1989. This public-school-choice policy permits students to attend another district without the burden of relocation or tuition payments. Today, more than 70,000 Ohio students use open enrollment to cross district lines. Forty-three other states allow some form of interdistrict open enrollment.

But here’s the hitch. Under Ohio policy, each district decides whether to participate in open enrollment. Four out of five Buckeye districts agree to accept students from outside their zoned boundaries. Many of these districts have practical reasons to participate, as the funds associated with inbound students may help to widen academic offerings, ease local tax burdens, or simply deal with the fiscal consequences of enrollment loss.

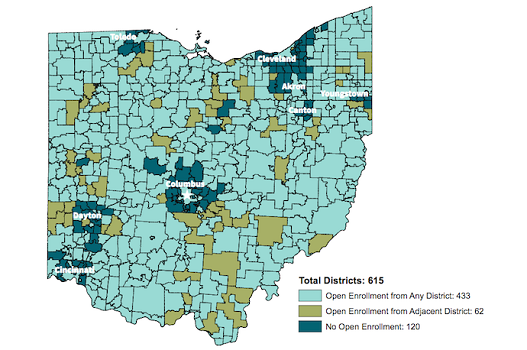

Of course, this also means that 20 percent of districts refuse to admit all comers. Figure 1 shows the systematic pattern of non-participation the Buckeye State: almost all of them serve suburban communities adjacent to Ohio’s largest cities. These major urban districts—including Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus—have student populations that are, on average, 63 percent black and Hispanic, and the districts have long struggled with low student achievement. In contrast, the non-participating districts on their borders enroll far fewer minority youngsters (18 percent) and post some of the highest test scores in the state. The dark blue “doughnuts” around the major cities clearly demonstrate how the refusal of most suburban districts to open enroll students severely limits the public school options of urban students who might benefit from exiting their home districts.

Figure 1. Ohio school districts by open-enrollment status: 2013–14 school year

A new Fordham study, Interdistrict Open Enrollment in Ohio: Participation and Student Outcomes, finds that less advantaged students do indeed appear to benefit from open enrolling. Researchers Deven Carlson of the University of Oklahoma and Stéphane Lavertu of The Ohio State University examine student-level data from 2009 to 2014 to track outcomes of Ohio’s open enrollees. While most open enrollees reside in rural and small town areas—locales where virtually every district participates—sufficient numbers of urban or African American students open enrolled over this period to carry out a rigorous analysis of their achievement outcomes.

While not causal evidence, their analysis links open enrollment among African American pupils with gains of approximately 10 percentiles on state assessments—equivalent to moving from the 50th to 60th percentile statewide in math or reading achievement. Their analysis also relates open enrollment to positive gains among students (regardless of race) who reside in one of Ohio’s eight highest-poverty urban districts. These results likely overlap to a certain degree—city schools in Ohio are disproportionately black—and apply to pupils who open enroll over several years. Those who participate less consistently experience no distinguishable gains or losses, nor do open enrollees from smaller towns or rural communities. As for on-time graduation outcomes, they find a promising uptick for students who open enroll throughout high school, though only one cohort was studied.

The findings uncovered in this study parallel to some extent recent analyses of housing vouchers. According to research by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and colleagues, a federal program that transplanted families from inner cities into higher-income communities improved young children’s later-life outcomes, including college matriculation and adult wages. While not as far-reaching as relocation, the evidence from Ohio suggests that consistent interdistrict open enrollment among children from urban areas can also put them on a more promising trajectory, at least through their elementary and secondary years.

We acknowledge that some closed districts may not have the capacity to enroll many additional students. We also realize that some residents may not like the idea of educating kids whose families don’t pay taxes in their towns, whether those prospective arrivals live in poor urban areas or wealthy districts nearby. We understand too that, for many families, it’s simply impractical to make long, daily treks across district lines.

At the very least, however, we ask today’s walled districts to quit calling what they do “public education” because they don’t welcome everyone, and are functionally more like “private school districts” where the price of a home and the accompanying property taxes buy a seat for one’s child in the local school. We also suggest that residents of such places ask themselves whether it’s fair to criticize urban schools—district, charter, or private—when their own schools refuse to admit children living just a few miles away.

Many are wondering how to advance the upward mobility for low-income children. Of course, school reformers must remain focused on improving urban education (and increasingly rural schooling, as well). The data from Ohio also indicate that interdistrict open enrollment presents another viable option that shouldn’t get lost in the shuffle. But one barrier in Ohio—and we suspect in other places where open enrollment remains a local decision—is that some public school districts remain less than “open to all.” For the refusenik districts such as these, we urge their board members and superintendents—and voters—to reconsider their decision to wall off their public schools. Indeed, in the spirit of President Reagan, we say please tear down those walls.

Aaron Churchill is an Ohio Research & Data Analyst for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Chad Aldis is the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy.