College readiness of Texas high school graduates has plummeted. This does not mean quite what it seems: students are not necessarily less ready to go to college. But it will have a real effect on their opportunities.

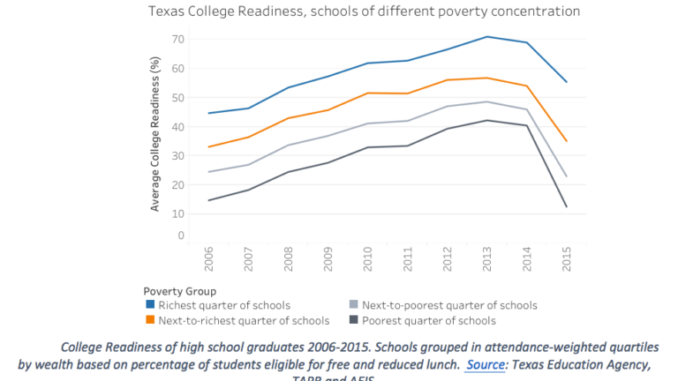

Texas began reporting college readiness of high school graduates for the year 2006, after legislation required “… the measure of progress toward preparation for postsecondary success.” It rose year after year until it reached a peak for the class of 2014. Then it plummeted, undoing a decade of progress. For graduates from the quarter of schools with the lowest concentration of low-income students, college readiness fell from 71 percent to 55 percent. For graduates from the quarter of schools where poverty is most highly concentrated, college readiness dropped from 42 percent to 13 percent. Hopes to increase the fraction of Texas youth who complete college degrees or post-secondary certificates are being dashed.

College readiness had to be defined to be measured, and this was done by checking that high school graduates reached specific scores on state mathematics and English language arts tests. They also could demonstrate college readiness by achieving specific scores on the SAT or ACT. Until 2013, the state exams used to determine college readiness were required for high school graduation, so almost all students took them. That changed in 2013, when the Legislature eliminated the end-of-course exams upon which college readiness was to be based. Now students can take the Texas Success Initiative Assessment (TSIA), but unlike previous state tests, which had been required for graduation, this new exam is optional.

The collapse in college readiness does not mean that teachers have in one year mysteriously forgotten how to teach, nor that principals lost their leadership skills nor that students became less able to learn. Students became less likely to take a test, for the simple reason that no one made them take one anymore. The official description of the result — as “college readiness” — is somewhat misleading because colleges and universities are actually forbidden from using it as a condition of admission.

Nevertheless, plummeting college readiness has its consequences. Once students pass exams that place the college-ready flag next to their names in state computer systems, they are allowed to walk into any two-year Texas community college after graduation, or four-year college program into which they are accepted and start taking credit-bearing coursework towards degree or certificates.

What happens if they don’t have that flag?

Imagine it is your child. He didn’t want to go to college, blew off taking TSIA in high school (you probably didn’t know it was an issue), graduated with adequate grades and went to work at a local garage doing brake repairs and rotating tires. He wants his bosses to trust him working on engines and to be ready to work on hybrid or fully electric vehicles, so after working two years, he decides to get an associate’s degree in automotive technology at the local community college. At step 7 of the admissions process, someone asks if he is college ready (he isn’t) and walks him to a room where he can take TSIA. The test is full of algebra, which he last saw three years before and never expected to see again. He doesn’t pass. So he finds himself diverted to developmental mathematics courses, which he absolutely must get through before anyone lets him actually start taking courses on automobiles. The odds are terrible. The chance of eventually getting out of developmental mathematics and passing college algebra as needed for his associate’s degree is less than one in six.

In fact, for Texas students who sought two-year degrees at two-year colleges in the fall of 2013 but needed developmental coursework, only 13 percent finished within three years, with another 25 percent persisting. That compares with around 60 percent achieving degrees or persisting among the students who left high school college ready. One student has put it this way: “This developmental algebra is a stainless-steel wall and there’s no way up it, around it or under it.” The precipitous drop in college readiness leaves many more students behind the wall.

Texas has an ambitious plan, 60×30, for 60 percent of Texas youth to have college degrees or certificates by 2030. The state may have been on track to reach it, but suddenly 10 years’ work enabling students to progress is undone. Unless support for students is returned, the hope and justice college means is lost; the lessons of the past have been unlearned, the state will pay the economic cost.

Michael Marder is a Physics professor at UT-Austin.