In key states that swung from red to blue, young voters of color may have ‘single-handedly made Biden competitive.’

This article was originally published at The 74.

As an undocumented immigrant, 19-year-old Juan Cisneros was ineligible to vote in the presidential election. But that wall separating him from the ballot box — paired with a president who made anti-immigrant rhetoric a staple of his administration — became a source of motivation.

Rather than casting a ballot himself, he urged his college-aged peers, who traditionally have a poor track record of showing up on Election Day, to make their voices heard.

“Being able to get other people to go out and vote is my form of voting,” said Cisneros, a computer science student at Benedictine University, a private Catholic school in Mesa, Arizona. As a fellow with the nonprofit immigrant-rights group Aliento, he joined a get-out-the-vote campaign that encouraged more than 25,000 young and Latino voters in the Phoenix area to participate in the election. “I was able to convince three other friends that weren’t really sure about wanting to vote to go vote.”

Efforts by Cisneros and other young people across the country may have been crucial to President-elect Joe Biden’s success. That’s especially true in several key states like Arizona and Georgia, where Biden outpolled President Donald Trump by more than 11,000 and 14,000 votes, respectively. A Democratic presidential candidate hasn’t won either state since the 1990s. In Georgia, young voters have another chance to reshape federal leadership when both of its U.S. Senate seats go to a runoff election in January.

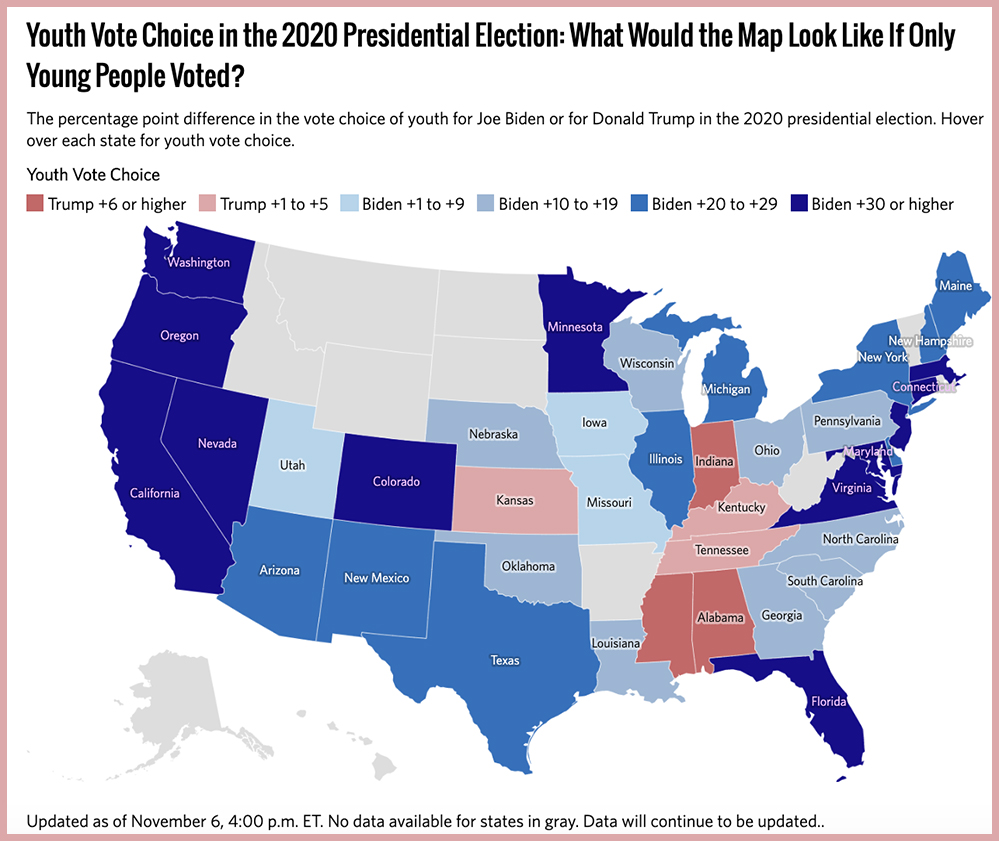

An estimated 50 to 52 percent of eligible Americans 18 to 29 years old cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election, according to an analysis by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University. That’s a sizable surge in youth participation from just four years ago, where it was between 42 and 44 percent. This year, nearly two-thirds of young people cast ballots for Biden, according to CIRCLE.

Though voter turnout spiked this year among all age groups, young people also made up a slightly larger percentage of all voters than they did in 2016, making their support for Biden even more critical.

“Young voters, especially youth of color, powered Joe Biden’s victory,” according to CIRCLE, a leading authority in research on youth civic engagement. “In fact, in states like Georgia and Arizona, Black and Latino youth may have single-handedly made Biden competitive.”

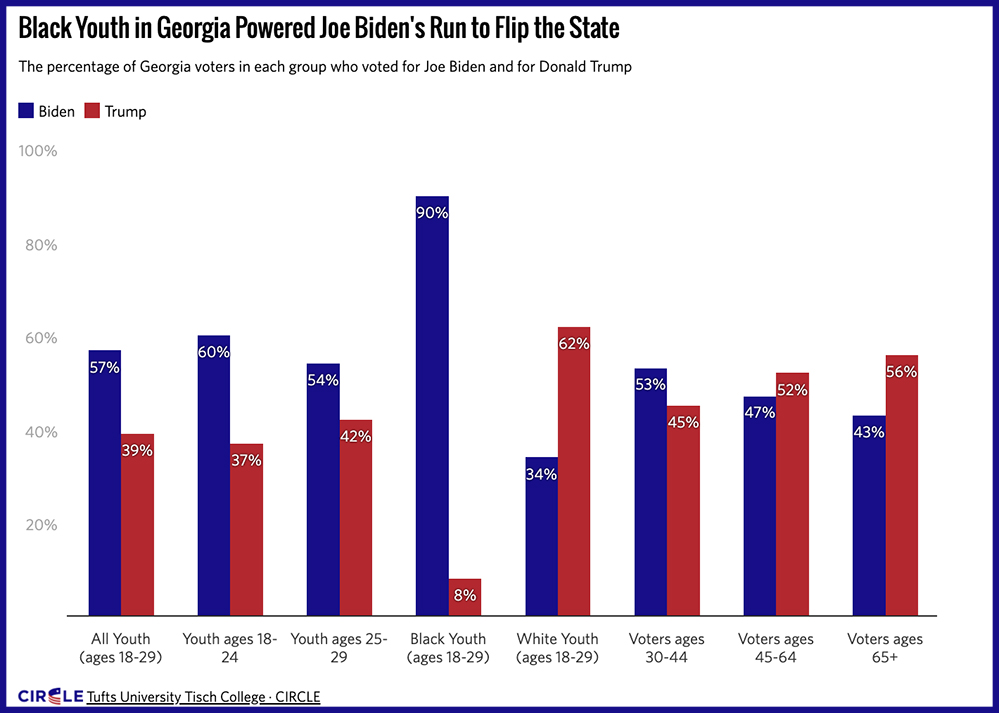

In Georgia, Biden received an estimated 188,000 more votes from young voters than Trump, according to CIRCLE estimates. While Biden secured an estimated 57 percent of young voters in Georgia compared to 39 percent for Trump, the results varied starkly by race. About two-thirds of Georgia’s white youth voted for Trump — but a resounding 90 percent of young Black voters supported Biden.

In total, Georgia voters 18 to 29 years old made up 21 percent of all votes, 4 percentage points above the national average and a larger share than anywhere else in the country.

The youngest voters in Georgia were particularly crucial, CIRCLE found. While an estimated 54 percent of Georgia youth 25 to 29 years old voted for Biden, the president-elect’s support spiked to 60 percent among those 18 to 24 years old.

A blue wave in Georgia has been years in the making. Abby Kiesa, CIRCLE’s deputy director, attributed the rise to sustained youth outreach.

“What we’ve seen over the years with respect to youth engagement is not that young people don’t care,” she said, but are often confused by the process as first-time voters. But a get-out-the-vote effort spearheaded by Stacey Abrams through groups like the New Georgia Project “helped connect the election to their everyday experiences.”

After losing her 2018 gubernatorial bid where there were widespread allegations of voter suppression, Abrams went on to help register more than 800,000 new voters.

A united front

Among those new voters was Cameron Nolan, a 21-year-old senior at Morehouse College and president of the historically black institution’s student government association. Though results of the presidential race are now being recounted by hand in Georgia, Biden maintains a lead that election observers say will not be undone, one that may not have materialized had young voters — and Black youth in particular — stayed home on Election Day.

After Abrams lost the governor’s race, Nolan said young voters in his state formed “a united front,” leading to a civic participation surge that turned Georgia blue for the first time in decades.

“A lot of it comes from the fear of the unknown and understand that ‘Alright, we just experienced four years of this particular presidency, are you really comfortable enough with doing another four?’” he said. “For a lot of the young voters whose visions didn’t necessarily align with the president, it became a space where you could say ‘Alright, this is what we could possibly do if we band together.’”

Abrams’s narrow defeat helped Georgia’s Black community understand that they wield significant power, said Nolan, who’s majoring in economics and has accepted a job at Salesforce after graduation.

“It was like “OK, this is the power that we can have if we move as a collective,’ and I think the young Black voter community completely understands that now,” he said. “I just have a large appreciation for the way the youth were able to come up in this election.”

Nolan, who wasn’t old enough to vote in the 2016 election, said the top issues motivating his vote for Biden included climate change and the president-elect’s proposals on college affordability. He also lauded Biden’s proposed $70 billion federal investment in historically black colleges and universities like Morehouse, and blasted Trump on issues of race. After George Floyd’s death at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer this summer, Nolan used his skills as a filmmaker to share his perspectives on being a Black man in America.

“The Trump presidency led to a lot of overt racism — not to say that racism was incited by President Trump, not to say that he created it — but merely him being in office was representative of individuals being very comfortable with their own personal racist views,” he said. Especially in the Deep South, Trump flags and the Confederate Flag were closely aligned, he said. “These past four years have been kind of unsettling.”

Ahead of the presidential election, the Morehouse College Student Government Association launched nonpartisan get-out-the-vote efforts, which centered largely on social media campaigns because of the pandemic as students attended classes virtually. Efforts included a voter registration drive and providing students with sample ballots so they knew what to expect on Election Day.

But even with the presidential election in the rearview mirror, the student group’s work is far from over. The runoff election in January will decide both U.S. Senate seats — and the central issue of whether the GOP, which has dominated Georgia politics for longer than these voters have been alive, will maintain its control of the chamber. For Georgians who were too young to participate in the presidential election, the January runoff will also be their first chance to cast a ballot.

“A lot of our future efforts will definitely be centered around voter education because we can’t necessarily tell you who to vote for, but my ask is that you always make an informed vote,” Nolan said.

Biden and Latinos

To Cisneros, the presidential election’s outcome was critical to his livelihood and to those of other undocumented people. In Arizona, where Biden was declared the winner Thursday, 68 percent of Latino youth voted for him.

Cisneros, a college sophomore, was born in Mexico but moved to Arizona with his mother on his 7th birthday to escape an abusive father and because of a medical condition. He arrived at a Phoenix trailer park in June 2008 — too late to be eligible for the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which protected young people who had been in the U.S. since 2007.

Over the course of his term in office, Trump waged a yearslong effort to end the DACA program and cracked down on undocumented immigrants. As the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement ramped up workplace raids, Cisneros lived in a state of paralysis and feared that his mother, a hotel housekeeper, could get swept up by ICE.

“There was a sense of panic,” he said. “Every single noise that I heard outside, I looked outside and tried to see if it was ICE or something. We didn’t even leave the house during that time. A lot of people in the community were feeling the same way I was feeling.”

Biden’s victory gives him a sense of optimism. Biden has promised to make immigration reform a top priority, but his success could be hindered if Republicans maintain control of the Senate. And despite Biden’s promise of creating a pathway to citizenship for an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants, Cisneros isn’t holding his breath.

“The pathway to citizenship is something we’ve been promised since Obama and it still hasn’t happened,” he said. “Sure, you can keep your hopes up, but until it happens, you’re going to be very skeptical about what they’re saying.”

Reyna Montoya, Aliento’s founder and CEO, said her group focused on youth engagement because encouraging people to become first-time voters comes with lifelong implications — and in turn could improve the lives of immigrants who are affected by the outcome of elections but are unable to participate themselves.

“Every single decision, from the pandemic to immigration, it includes all of us,” said Montoya, a DACA recipient who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico in 2003. “I think we have a unique opportunity to ensure that we’re listening to our young voices, the young people who are going to be leading in the future.”

But she also declined to give Biden a ringing endorsement. Deportations surged under Obama, and immigrant rights groups famously labeled him the “Deporter in Chief.” It was during the Obama administration, in 2012, when immigration officials detained her father for nine months before his release. He was just recently granted asylum, she said.

But because Obama approved the DACA program, Montoya said his legacy offers “a bittersweet taste.” In an effort to distance himself, Biden, who served as Obama’s vice president, has called the former president’s immigration record a “big mistake.”

That’s why it’s important to hold Biden accountable to his promises, Cisneros said. In fact, he accused Biden and the Democratic Party of taking Latino voters for granted. Biden’s lackluster performance with older Latino voters may have handed him defeats in Florida and Texas.

“The younger voter population showed up in Arizona and all across the country,” he said. “I think that if Biden doesn’t do something like a pathway to citizenship and extend DACA, the chances of being reelected are going to be lowered due to the Latinx community.”

Playing the long game

Even after Georgia’s January runoff, Kiesa of CIRCLE noted that efforts in the state could be instrumental in elections for years to come. That’s because the state’s sustained get-out-the-vote campaigns offer a roadmap moving forward for groups interested in increasing civic participation.

“We cannot wait until the last three months before an election and think that we’re going to dramatically change turnout,” she said. “We need both campaigns and people outside of the partisan environment to be thinking about that work.”

Among them, she said, are K-12 teachers. In a pre-election survey, CIRCLE found a relationship between civics education in high school and young voter turnout. Young people who said they were taught in high school how to register to vote and were encouraged to show up on Election Day were more likely to follow through. They were also more knowledgeable about voting processes and were more invested in the 2020 election.

In total, nearly two-thirds of survey respondents said they were encouraged to vote in high school and half said they were taught how to register to vote — but the results also found stark racial disparities. While two-thirds of white respondents remembered being encouraged to vote in high school, just half of Black participants recalled similar experiences in high school.

“This is one of the reasons why we believe the education system can be so critical in reducing some of these inequities we see within our systems of election,” she said. “Teachers and K-12 leaders and election officials can all focus a great deal more on that 16- to 18-year-old range — and even earlier if possible — to really make sure that we have a more representative youth electorate.”

Mark Keierleber is a senior writer-reporter at The 74.