by Michael Hiltzik

California’s nation-leading embrace of the Affordable Care Act began with a Republican governor.

Arnold Schwarzenegger had been trying since 2007 to create a universal healthcare program for the state. He had reached an agreement with then-Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuñez (D-Los Angeles) to impose an individual mandate — a requirement that almost all Californians carry health insurance — while providing subsidies for low-income residents. His plan, drawing from the program implemented in Massachusetts under then-Gov. Mitt Romney, would forbid insurers to turn away people with preexisting medical conditions.

In the end, the cost of the program, estimated at $15 billion in 2008, when recession was beginning to bite, sank its chances in Sacramento. But the work done on the proposal placed the state in a perfect position to fully exploit the Affordable Care Act when it came into existence two years later.

California made the right bets…. The ACA is about health being a public good.

“Those of us who worked on the legislation understood that a lot of what was in the Affordable Care Act was a reflection of the work that California had done,” recalls Deborah Kelch, who was a legislative staffer during the California push and went on to become executive director of the Sacramento-based Insure the Uninsured Project.

“There was a lot of desire and effort in the Schwarzenegger administration and the Legislature to do something like the ACA,” Kelch says. “So when the ACA came, we were particularly well situated to take advantage of it and go forward.”

With the Affordable Care Act’s tenth anniversary upon us — President Obama signed the measure on March 23, 2010 — it’s evident that California’s full-scale embrace of the law has yielded dividends for the state, its residents and even the federal government, measured in the billions of dollars and millions of covered enrollees.

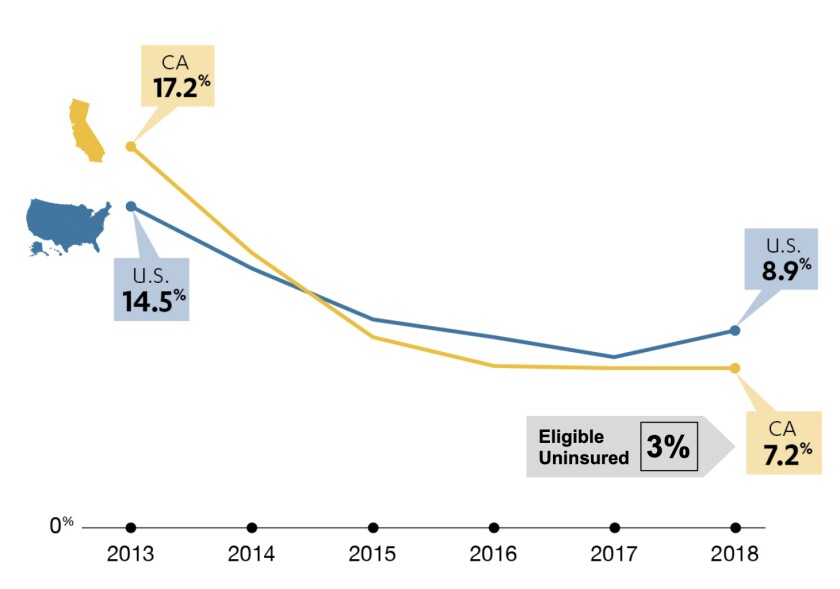

Since the inauguration of the individual insurance exchanges in 2013, California’s uninsured rate has fallen by 10 percentage points, to 7.2%. That’s the largest drop in the nation. Among “eligible uninsured” people — that is, excluding those barred from participating because of their immigration status, such as adult undocumented residents — the rate is even lower, 3%.

“California made the right bets,” says Peter V. Lee, executive director of Covered California, the state’s ACA insurance exchange.

What inspired Schwarzenegger in 2007, and the state’s leaders since then, was the realization that healthcare is in the community’s interest — that a hole in the public health safety net affecting any individual or family is a danger to all. Nothing has brought that fact to the nation’s consciousness like the current coronavirus crisis.

“If you think you can be an island unto yourself and not worry about the health of your neighbor, there’s no better lesson than what we’re seeing with this virus,” Lee says. “I want my neighbor, my co-workers, the kids going to school with my children to be vaccinated when they should be and treated with ready access to affordable care.”

While California’s approach to coverage may have given it a leg up in grappling with the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, it’s still hampered by attacks on the ACA taking place outside its borders.

The most serious threat is a lawsuit brought by Texas and 17 other red states aiming to declare the entire law unconstitutional. The Supreme Court agreed earlier this month to review the case, which means the ACA’s fate will be up in the air at least until the end of the year. A ruling overturning the law will undo much of what California has accomplished.

After the ACA’s enactment, Schwarzenegger became the first governor in the nation to announce that his state would form its own insurance exchange and appointed a task force to create it.

The state’s acceptance of the law continued with Gov. Jerry Brown, who took office in 2011. Brown expanded Medi-Cal, California’s version of Medicaid, to take advantage of the federal government’s 100% funding for the expansion population starting in 2014. (The federal match fell in stages to the current, permanent level of 90%.)

Despite the obvious fiscal and public health benefits of expansion, 14 states — all controlled by Republican legislatures or governors — still haven’t accepted it.

The state took pains to avoid pitfalls in implementing the law. Covered California chose to create an “active” insurance exchange, in which it would set benefit and quality standards that participating insurers must meet, whereas other states and the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov, accommodated all insurers willing to meet the ACA’s less stringent standards.

The California exchange told insurers that it would monitor the adequacy of provider networks to ensure that they included a sufficient selection of primary care doctors, specialists and accessible hospitals. Insurers had to report regularly on how they cared for patients with chronic conditions requiring coordinated treatment, such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension and heart disease. They would be judged on how they managed enrollees requiring expensive specialty treatments, such as those with rare cancers or transplants or who required end-of-life care.

By standardizing plans, Covered California forced insurers to compete chiefly on price, rather than benefit peculiarities that might be hard for consumers to understand. The exchange also maintained a vigorous marketing and outreach program that is still budgeted at about $100 million.

By contrast, the Trump administration cut the nationwide marketing and promotion budget for the ACA by 90%, to a mere $10 million. The Trump administration has made other moves to undermine the ACA, including reducing the open enrollment period by weeks. California has kept the open enrollment period at Oct. 15 to Jan. 31, although late enrollees won’t be able to start their coverage until after Jan. 31.

Trump and the Republican congressional majority also reduced the individual mandate penalty to zero as part of the December 2017 tax cut bill. Removing the federal penalty as of January 2019 had a measurable effect on enrollment, experts have found. Covered California blamed its 24% drop in new enrollments for 2019 almost entirely on the penalty’s elimination.

“Even robust marketing cannot offset the negative impact of its removal,” the California exchange said.

The result of Trumpian sabotage has been a sharp 13.5% drop in nationwide enrollment through the federal government’s HealthCare.gov exchange, to 8.3 million in December 2019 compared with peak enrollment in 2016.

At Covered California, which is largely if not entirely insulated from federal policy, the drop has been a more modest 2.3% over that period, to 1.54 million. Some of that can be attributed to the end of the federal penalty, but some may also be caused by rising premiums, which affect households with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies.

California’s enrollment includes more than 418,000 consumers signing up for the first time, an increase of 41% over the previous year. Medi-Cal’s expansion enrollment was about 3.4 million as of September.

California took other steps to keep younger, healthier customers in its individual insurance pool despite sabotage at the federal level. The state banned the sale of short-term insurance plans, which aren’t subject to ACA consumer protections that guarantee affordable coverage to people with preexisting conditions and bar annual or lifetime coverage limits.

The Trump administration has promoted these plans because they’re cheaper than full-scale ACA coverage, but that’s because they’re riddled with coverage gaps and can reject applicants with potentially costly conditions. Their low prices, however, could siphon healthier customers out of the ACA pool.

“Short-term plans are a return to the Wild West of health insurance before the ACA,” Lee told me. “One of the big lessons from the pre-ACA days is that you can get a lower-cost plan if you can exclude people and you’re not there when your customers get cancer. That’s not California’s play.”

By maintaining standards, California avoided many of the travails of the ACA market in other states — “phenomenal instability, with plans coming and going, insurers losing hundreds of millions of dollars, consumers facing huge uncertainty,” Lee observed.

The uncertainty has contributed to an increase in benchmark ACA plan premiums of 79% since 2014 nationwide, compared with the increase of 45% in California. The figures refer to gross premiums, before tax subsidies. The benchmark premium, which is charged by the second-cheapest mid-range silver plan in each region, is used to calculate federal subsidies.

While some other states struggle to attract insurers to cover their entire territory, California’s roster of participating insurers has remained at 11 companies (though one carrier left and another came in). About 99% of state residents can choose from at least two insurers in their parts of the state; 27% of enrollees can choose from six or more.

California has fought back against other federal initiatives aimed at chipping away at the ACA. Last year the state enacted its own individual penalty for not carrying insurance. This was a response to the reduction of the federal penalty to zero.

The state’s penalty, effective this year, is set at the same level as the former federal penalty — 2.5% of household income or $695 per adult, whichever is greater, with a family maximum of about $2,100.

California also expanded premium subsidies beyond the federal rule, which grants subsidies to households with earnings up to 400% of the federal poverty level ($104,800 for a family of four). California will provide subsidies for households with earnings up to 600%, or to $157,200 for a family of four, thus considerably improving the affordability of plans on the individual exchange for middle-class families.

For 2020, Covered California extended the open enrollment period to April 30 to accommodate applicants unaware of the state’s imposition of its own individual mandate penalty or its expanded premium subsidies.

The state also expanded Medi-Cal eligibility to undocumented young adults up to the age of 26; those younger than that had already been granted eligibility in 2015.

California’s capacity to stand fast against threats to the ACA isn’t infinite. “There have been attempts to kill the ACA by a thousand cuts, but they’ve hardly affected California at all because we’ve been able to counter virtually all of them,” Lee told me. The Texas lawsuit, however, is a dark cloud, for an adverse ruling by the Supreme Court would eliminate funding for the Medicaid expansion and premium subsidies.

“We could never counter taking away that money,” Lee said. “Medicaid expansion and premium subsidies would go away, as would protection for preexisting conditions, as would tens of billions of dollars for preventive health and public health, which is relevant to the current virus. The ACA was about health being a public good.”

Most important, without the Affordable Care Act, 17% of Californians would be uninsured. “Being uninsured is a public health catastrophe,” Lee says. “Having so few people uninsured is good news when you have the worst happening in healthcare.”

California has known that for years. The rest of the country is just learning.

Michael Hiltzik writes a daily blog appearing on latimes.com. His business column appears in print every Sunday, and occasionally on other days. As a member of the Los Angeles Times staff, he has been a financial and technology writer and a foreign correspondent. He is the author of six books, including “Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age” and “The New Deal: A Modern History.” Hiltzik and colleague Chuck Philips shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for articles exposing corruption in the entertainment industry.