by Esmeralda Fabián Romero

This article was originally published at LA School Report.

Nearly 60 percent of children in L.A. County have at least one immigrant parent, according to a new report by the USC Center for Immigrant Integration which highlights deep disparities in education and the workforce among Latino and black immigrants.

The report, “State of Immigrants in LA County,” and the challenges faced by immigrant students and the children of immigrants across L.A. schools were among the main topics of discussion at the first “The Future of Immigrants in Los Angeles” summit in downtown L.A. on Jan. 9.

The USC report was released at the summit, where more than 300 community leaders representing dozens of local and nationwide organizations, as well as elected officials, educators and pro-immigrant advocates, gathered at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels to discuss why immigrant parents’ civic engagement and empowerment are crucial for these students to succeed.

Efrain Escobedo, vice president of education and immigration for the California Community Foundation, said that policymakers and school districts need to understand the disparities and how anti-immigrant policies around deportation impact learning for those children.

“What this report does is to have schools recognize that we have to look at families and we have to look at communities. These students are bringing needs that are impacted by the economic inequalities that exist in the county, that are impacted by the anti-immigrant policies around deportation,” Escobedo said. “All of these things affect the learning process for these immigrant children. What this report does is provide that bigger picture for school districts to understand what might be the other contributing factors that we need to think about and will force districts, I think, to say we need to partner with not just families, but with organizations.”

Manuel Pastor, director of the USC Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, said that while the findings are not surprising, they make it clear that school funding and greater parent involvement are critical in helping close the achievement gap for children of immigrants.

“One of the things you notice, particularly in smaller suburban districts, is that parents are as engaged as they might be, and we know that when parents are engaged, their children do better. Parents are also demanding better systems for their children, etc.,” Pastor said.

He noted that language limitations continue to be one of the main obstacles for immigrant parents to be involved in their children’s education and that schools need to do a better job of introducing them to the idea of being part of the PTA or school site councils.

“I think we face a number of different challenges. People who are immigrants, people who are undocumented, can sometimes be afraid of participating in a public sphere,” Pastor said. “Schools aren’t always welcoming to them either in terms of having meetings and the languages they’re most comfortable with or even really welcoming parents to be fully engaged.”

Escobedo also highlighted parent engagement and representation as a key to the educational success of children of immigrants.

“I think it is critically important that, just as with students, for parents to feel like they can engage and feel connected to the school, which in some way is influenced by who represents the leadership in the school, what the teachers look like, what the cultural competencies of the administrators are, to understand the culture they serve in their local communities,” Escobedo said. “Very specifically, do you have administrators of color? Do you have administrators that represent the immigrant communities that they’re serving? People need to feel comfortable and trusting in wanting to collaborate and feel welcomed at schools.”

“That’s really critical,” Pastor said. “I think that is as important as being able to vote in school board elections, the signal it sends that you’re welcome, that you’re a full participant in determining the education of your children.”

Giving non-citizen families a voice

The report found that 20 percent of L.A. County’s population either are undocumented themselves or live with someone who is, and that 1 in 3 Angelenos is foreign-born.

It also shows how that status is a major determinant in attaining higher education, with 33 percent of naturalized citizens in L.A. holding a bachelor’s degree, compared with the 23 percent of immigrants who are permanent residents and have graduated from college. Only 9 percent of undocumented immigrants hold a college degree or higher, and 60 percent don’t have a high school diploma.

Last year, Los Angeles Unified School District passed a resolution proposed by board member Kelly Gonez to explore a city ballot initiative giving all non-citizen parents within LAUSD’s boundaries the right to vote in school board elections. One board member, George McKenna, abstained from voting either for or against the resolution, citing concern around voter confidentiality and fears that non-citizens’ personal information would be breached and used to harm immigrant families.

Gonez, who participated in last week’s summit and has an immigrant parent, emphasized that her resolution takes into account the protection of voter confidentiality. Multiple immigrant-rights groups support it, including several of those at the summit.

“Having an opportunity to have a voice about who represents the interest of your child on a school board is fundamental, so we should get that done right away,” Escobedo said. “It’s not about straight legal status, citizenship. It’s about, am I a stakeholder as a parent in this district, and if so, then I should have the right to choose who makes decisions for my child.”

“Even in Los Angeles, there is more work to be done to create an inclusive city where our immigrants can lead and thrive,” Gonez said in a statement on Jan. 14. “I plan to bring the energy and urgency that fueled our conversation to LA Unified as we begin the study group to pursue this change. It’s one concrete way to ensure our families have a voice and that our representatives better reflect their communities.”

At the board meeting that same day, Gonez also introduced a resolution that would demonstrate the district’s opposition to the proposed opening of a migrant youth detention center by a private company in the district she represents or anywhere within LAUSD’s boundaries.

“A youth migrant detention center has absolutely no place in the East San Fernando Valley or anywhere in Los Angeles Unified,” Gonez said during the meeting. “It is antithetical to our community’s values and our mission to create safe supportive spaces for young people. We are calling on the Los Angeles City Council to do everything in its power to stop the detention center from opening.”

The resolution that was approved unanimously by the board on Tuesday states that the district served about 13,000 newcomer students (newly arrived immigrants) in the 2018-19 school year and expects to serve 17,000 this school year.

Reimagining education for English learners

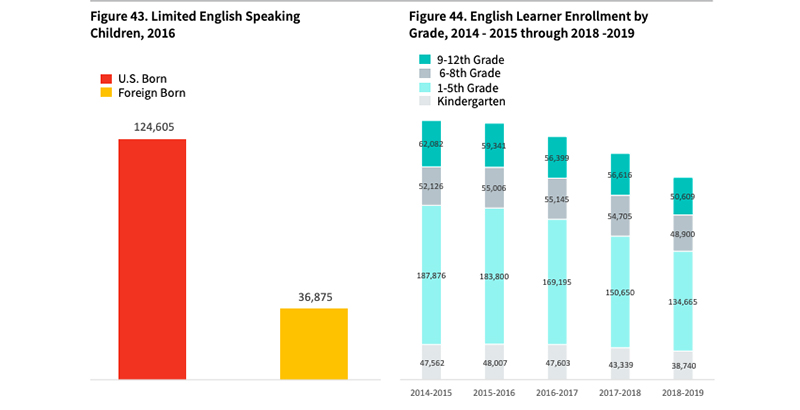

English-speaking proficiency was named as a challenge in the report for L.A. County, where nearly 37,000 immigrant children have limited English-speaking ability, as do 125,000 children who are U.S. born.

More than 305,000 of the county’s 1.5 million K-12 students were classified as English learners in the 2018-19 school year, according to the Los Angeles County Office of Education, which offered an education session at the summit.

In L.A. Unified and at the state level, English learners have ranked at the bottom of all student subgroups in the state proficiency test, known as CAASPP, for the past three years.

“When it comes specifically to English learner students or bilingual education, I would say, first and foremost, we need to radically reimagine our classrooms and the cultures in our schools,” Escobedo said, adding that 2016’s voter repeal of Prop. 227, which had mandated English-only instruction in California since 1998, gave advocates and educators the ability to do that.

“I think what we need in our schools is not just, how do we improve the outcomes of English learners under our current assessment, but how do we reimagine education and our culture to be a truly global multilingual education system, which we’re not,” Escobedo said. “So we could tinker around, but until we say we need to dismantle the English-only system we used to have and reinvent one that prizes multilingualism and multiculturalism, then, I mean, we’re not going to get transformation. We’re just going to get shifts.”

Esmeralda Fabián Romero is a senior reporter at LA School Report. @EsmeFabianTV