by Kevin Mahnken, the74

Scores released today from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) held bad news for American schools, with trends that are essentially flat in mathematics and down in reading. Most states saw little or no improvement in either subject, with their lowest-performing students showing the most significant declines in scores. Whether the cause lies in hangover effects from the Great Recession, missteps in federal education policy, or some combination of these and other factors, there has been little progress to be assessed for over a decade.

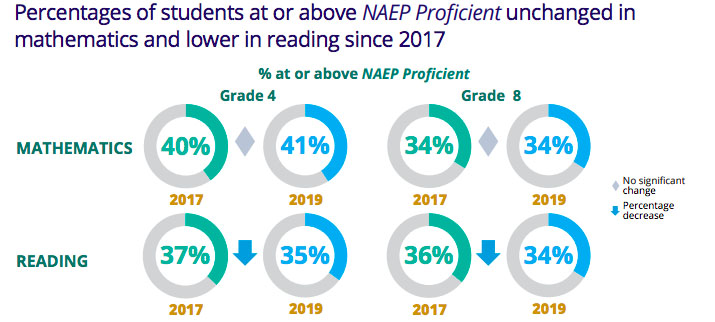

Overall results for eighth-grade reading — the lone, if modest, highlight in 2017’s scores, with a gain of a single point that year — provided the greatest cause for discouragement this time around, sinking by three percentage points. The percentage of fourth-graders testing “proficient” in the subject (a higher bar, by NAEP’s definition, than simply reading on grade level) dropped from 37 percent in 2017 to 35 percent today; the percentage of proficient eighth-graders sagged from 36 percent to 34 percent over the same period.

“It’s really sad,” said Joanne Weiss, an education consultant who ran the Race to the Top Program under Obama-era Education Secretary Arne Duncan. “It’s heartbreaking, especially the reading results and the results for the lowest-performing kids.”

NAEP was first administered in 1969 as a measure of fourth- and eighth-graders’ achievement in the core areas of reading and math. The biannual release of test results by the National Center for Education Statistics, in a package of national- and state-level data commonly referred to as the Nation’s Report Card, has offered a regular checkup on how students of different racial, ethnic and geographic backgrounds are learning.

Since late in the presidency of George W. Bush, the trend has been one of stasis. Scores have barely moved for any subject-grade combination in over 10 years, as NCES Associate Commissioner Peggy Carr told reporters on a media call ahead of the release. For some students, she added, the inertia extends back over a quarter-century.

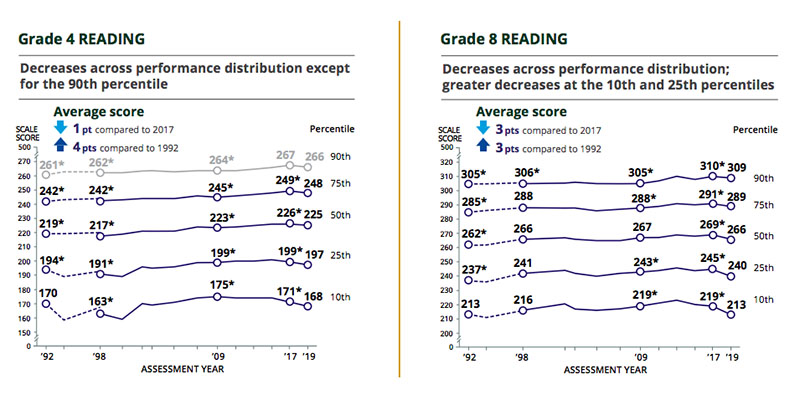

“Since … 1992, there has been no growth for the lowest-performing students in either fourth-grade or eighth-grade reading,” she said. “That is, our students who are struggling the most at reading are where they were nearly 30 years ago.”

Weiss blamed the lack of upward movement in the subject on an ignorance of prevailing literacy research. Experts have complained for decades that many young children are inadequately exposed to phonics-based instruction, leading them to miss important reading milestones early in their school careers.

“We have an education system that’s largely ignoring, or doesn’t understand, the research on teaching skills to read — the foundational skills, the decoding skills,” she said. “We just don’t really pay attention to the research about how to get every child reading by third grade, even though it’s pretty well documented how to do that.”

While students at all performance levels scored worse in both fourth-grade and eighth-grade reading, those downticks were larger for struggling students (those who scored at the 10th and 25th percentiles, respectively). This grim development somewhat echoes a trend noted in 2017, when a widening gap became evident between the highest- and lowest-scoring students. This year, the top performers saw either stagnation or meager decreases, while the lowest-scoring test takers slid substantially, particularly in reading.

Few exceptions to stagnation

With each NAEP release, education observers home in on which states and cities defied trends by performing better than their peers.

This year, there are few shining stars. Forty states maintained roughly the same performance in fourth-grade math, and 43 did the same in eighth-grade math. For reading, disappointment was widespread: Students in an incredible 31 states performed worse in eighth-grade reading than they did in 2017.

Only two jurisdictions saw statistically significant improvements over their 2017 performance in three out of four subject-grade combinations: Mississippi and Washington, D.C. On the media call, Carr observed that both jurisdictions achieved the highest score gains in the history of their participation on NAEP.

Washington — a mecca for education reform that has implemented an exacting school-quality framework and encouraged a wide proliferation of charter schools — was also something of a success story in 2017, when both the charter and traditional public school sectors showed notable improvement over the previous decade.

Thomas Dee, a professor of education at Stanford University who has won awards for his research on Washington’s teacher performance system, said that the District’s continual upward trend could be attributable to its long-term emphasis on accountability.

While cautioning that NAEP scores “are not the most convincing evidence of [policy successes], or even close,” Dee said the city stood out for its teacher evaluation system, even as high-profile experiments in other areas have faced massive implementation challenges. Notably, local authorities are now weighing whether to overhaul the system by opening it up to collective bargaining, a step that some have warned could put recent achievement gains at risk.

“One of the ‘tells’ for success is whether cities were able to have variation in teacher ratings” — in other words, whether they consistently distinguished between effective and ineffective teachers — “and to use them consequentially for personnel decisions,” he noted. “D.C. is one of the few places that actually seemed to get that right. They have a high-fidelity implementation of teacher evaluation that actually generated meaningful variations in measures of teacher effectiveness.”

Mississippi has also made steady gains in both subjects over the past few years, winning specific praise from some reformers for the strides it made during the last round of NAEP testing. Since the state initiated a decade-long campaign to improve instructional rigor — including the adoption of more stringent academic standards and aligning its own state test with NAEP’s format and content — student performance has shot up in all subjects, including a 13-point boost in fourth-grade math and a nine-point increase in eighth-grade math since 2009.

Weiss said she thought other states could benefit from the example of those that have climbed rapidly.

“There’s lessons we can take from those places that have had serious and intentional strategies for academic improvement,” she said. “In Mississippi … they have had a significant focus at the state level on high-quality instructional materials, with professional learning wrapped around it. It’s important to study those places and pay attention to what they’re doing.”

Apart from the limited good news at the state level, Dee called the lack of national progress “disturbing.” While NAEP scores offer limited insight into the success of American schools and students, we ignore the continued poor performance at our own peril, he said.

“Test scores are picking up measures of cognitive skills that matter not only for our children’s economic future, but that redound to multiple other dimensions of human welfare: their health outcomes, their likelihood of going to prison, the character of their civic engagement, which are all related to what they learn in school. This is why so many of us care about education. And we’re seeing our system challenged here in terms of realizing our children’s potential.”