by Ronald Brownstein

In an age of diminished resources, the United States may be heading for an intensifying confrontation between the gray and the brown.

Two of the biggest demographic trends reshaping the nation in the 21st century increasingly appear to be on a collision course that could rattle American politics for decades. From one direction, racial diversity in the United States is growing, particularly among the young. Minorities now make up more than two-fifths of all children under 18, and they will represent a majority of all American children by as soon as 2023, demographer William Frey of the Brookings Institution predicts.

At the same time, the country is also aging, as the massive Baby Boom Generation moves into retirement. But in contrast to the young, fully four-fifths of this rapidly expanding senior population is white. That proportion will decline only slowly over the coming decades, Frey says, with whites still representing nearly two-thirds of seniors by 2040.

These twin developments are creating what could be called a generational mismatch, or a “cultural generation gap” as Frey labels it. A contrast in needs, attitudes, and priorities is arising between a heavily (and soon majority) nonwhite population of young people and an overwhelmingly white cohort of older people. Like tectonic plates, these slow-moving but irreversible forces may generate enormous turbulence as they grind against each other in the years ahead.

Already, some observers see the tension between the older white and younger nonwhite populations in disputes as varied as Arizona’s controversial immigration law and a California lawsuit that successfully blocked teacher layoffs this year at predominantly minority schools. The 2008 election presented another angle on this dynamic, with young people (especially minorities) strongly preferring Democrat Barack Obama, and seniors (especially whites) breaking solidly for Republican John McCain.

Over time, the major focus in this struggle is likely to be the tension between an aging white population that appears increasingly resistant to taxes and dubious of public spending, and a minority population that overwhelmingly views government education, health, and social-welfare programs as the best ladder of opportunity for its children. “Anything to do with children in the public arena is going to generate a stark competition for resources,” Frey says.

The twist is that graying white voters who are skeptical of public spending may have more in common with the young minorities clamoring for it than either side now recognizes. Today’s minority students will represent an increasing share of tomorrow’s workforce and thus pay more of the payroll taxes that will be required to fund Social Security and Medicare benefits for the mostly white Baby Boomers. Many analysts warn that if the U.S. doesn’t improve educational performance among African-American and Hispanic children, who now lag badly behind whites in both high school and college graduation rates, the nation will have difficulty producing enough high-paying jobs to generate the tax revenue to maintain a robust retirement safety net.

“The future of America is in this question: Will the Baby Boomers recognize that they have a responsibility and a personal stake in ensuring that this next generation of largely Latino and African-American kids are prepared to succeed?” contends Stephen Klineberg, a sociologist at Rice University in Houston, who has studied the economic and political implications of changing demographics. “This ethnic transformation could be the greatest asset this county will have, with a young multilingual, well-educated workforce. Or it could tear us apart and become a major liability.”

The Changing Face Of America

At the root of the generational mismatch are federal policies that severely reduced immigration from the 1920s until Congress loosened the restrictions in 1965. With immigration constrained, whites remained an overwhelming majority of American society through the mid-20th century, including the years of the post-World War II Baby Boom. (Demographers date the Baby Boom from 1946 to 1964, the year before the restrictions on immigration were eased.) The result was a heavily white generation of young people.

“Most Boomers grew up and lived much of their lives in predominantly white suburbs, residentially isolated from minorities,” Frey wrote this spring. They are now graying into a senior generation that is four-fifths white, according to census figures.

Since 1965, however, expanded immigration and higher fertility rates among minorities have literally changed the face of America, particularly on the playground. As recently as 1980, minorities made up about one-fifth of the total population and one-fourth of children under 18. Today, the Census Bureau reports, racial minorities represent about 35 percent of the total population and 44 percent of children under 18. Whites make up 56 percent of young people and 80 percent of seniors. The 24-point spread between the white percentage of the senior and the youth populations is what Frey calls the cultural generation gap.

This split has widened rapidly over the past quarter-century. In 1980, it stood at just 14 percentage points, according to calculations performed by the Census Bureau for National Journal. The gap expanded to 18 points by 1990 and 23 points by 2000. Today, it is visible across a wide swath of the U.S. In 31 states, the difference between the white share of the senior and youth population is at least 19 percentage points.

Whites compose a majority of the senior population in every state except Hawaii. Minorities compose a majority of the youth population in seven states and at least one-third of young people in 17 more. In 11 states, minorities already represent a majority of elementary and secondary public school students. All of these numbers are likely to grow as the minority share of the youth population rises to nearly 55 percent by 2030 and almost 60 percent by 2040, according to Frey’s projections.

Although the phenomenon is evident in many regions, it is most acute in states with burgeoning Hispanic populations, especially in the Southwest. The largest cultural generation gaps are in Arizona (40 percentage points), Nevada (34), California (33), Texas (32), New Mexico (31), and Florida (29). In all of these states, a majority of young people are nonwhite (at least 56 percent in all but Florida), while at least three-fifths of seniors are white.

Across these states, the two groups’ contrasting perspectives and needs are fueling cultural clashes. Public schools are often an especially volatile frontier. In Texas, for instance, racial change was a charged subtext of a larger ideological battle this spring over history and economics textbooks in the public schools. In March, the Republican coalition that controls a majority on the Texas Board of Education imposed a more conservative presentation on a wide variety of American history topics. Among the amendments approved was one requiring students to be taught not only about Martin Luther King’s nonviolent philosophy during the civil-rights struggle of the 1960s but also about the Black Panthers’ preaching of violence.

Mary Helen Berlanga, a Latina board member, angrily complained that the textbook revisions eliminated discussion of a 1947 federal Appeals Court decision that barred segregation of Mexican-American students in Texas public schools. About 3 million of the students in Texas public schools are minorities. “Who are we kidding?” Berlanga asked. “These are the children that are going to be reading these materials. You want to talk about the Black Panthers in an ugly fashion? What about the Ku Klux Klan? That was a pretty nasty group. Why aren’t we talking about them?”

A similar dispute played out in Arizona this year. In May, Republican Gov. Jan Brewer signed legislation to cut state funds for school districts offering classes that were deemed to encourage ethnic solidarity or promote racial resentments. The legislation, promoted primarily by Tom Horne, the Republican state superintendent of public instruction, was aimed largely at the ethnic studies program in the public schools of Tucson, a metropolitan area where 60 percent of young people are minority but 80 percent of senior citizens are white. According to Frey’s figures, that’s the third-largest such gap for any metropolitan area in America, exceeded only by Phoenix and Riverside, Calif.

Arizona’s ethnic studies dispute, of course, was eclipsed by the searing controversy over another law that Brewer signed that gave police authority to detain anyone suspected of being in the country illegally. Arizona’s immigration law sharply divided the state along racial lines. In a May survey from the nonpartisan Behavior Research Center in Phoenix, almost 70 percent of Hispanics (and 63 percent of other minorities) opposed the law, while nearly two-thirds of white Arizonans supported it. National reactions to the Arizona immigration law have followed similar patterns.

From the front lines, these Texas and Arizona disputes exposed starkly different assessments of the nation’s ongoing demographic makeover. In varying ways, the proponents of the Texas curriculum changes and the Arizona immigration and ethnic studies laws portray their goals as upholding traditional standards — from respect for the law to a melting pot vision of American assimilation — in a period of rapid change. Horne asserts that the legislation he promoted on ethnic studies is meant only to resist separatism. “The purpose of the law,” he says, “is to prevent schools from dividing students by race and teaching them separately by race, and teaching kids ethnic chauvinism and hatred of others.”

Many supporters of these and similarly minded initiatives view themselves as a last line of defense against a flood tide of change threatening to sweep away national traditions. “The key thing that I wanted to make sure was for our kids to understand what makes America an exceptional place,” Don McLeroy, a member of the Texas Board of Education who led the effort to rewrite the textbook standards, said in an interview. “What I think is important is that we stick to the principles we were founded on and that our kids learn those principles as they were meant to be understood.”

Critics view these initiatives as thinly veiled appeals to whites who are uneasy about the racial change occurring around them. They commonly describe such proposals as trying to turn back the clock to the preponderantly white society that many of today’s seniors remember from their youth. In a typical assessment, Judy Burns, president of the Tucson Unified School District’s board, says of the attacks on the city’s ethnic studies classes, “It’s hard for me to believe there is no racism there.” In Texas, Berlanga similarly argues that the changes in the state curriculum constitute “an attack on minorities.” The conservatives who make up the school board majority, she charges, “want everything returned to the way it was in the 1950s, 1940s, 1930s.”

Across a charged cultural battlefield, one side sees a program of preservation, the other an agenda of exclusion. The distance between these perspectives isn’t likely to narrow any time soon.

Competition For Taxpayer Dollars

Although cultural disputes often generate the most heat, government budgets are likely to become the central point of conflict between younger minorities and older whites. At the state level, where governors are grappling with persistent deficits, the strains revolve around the choice between raising taxes or cutting spending. At the national level, Congress faces not only that familiar debate but also the competition between investing in education and other programs that benefit children, or spending on those that benefit seniors, primarily Medicare and Social Security.

Although cultural disputes often generate the most heat, government budgets are likely to become the central point of conflict between younger minorities and older whites. At the state level, where governors are grappling with persistent deficits, the strains revolve around the choice between raising taxes or cutting spending. At the national level, Congress faces not only that familiar debate but also the competition between investing in education and other programs that benefit children, or spending on those that benefit seniors, primarily Medicare and Social Security.

The entire white electorate has grown more skeptical about the value of public spending and the ability of government to solve problems even as Washington, first under President Bush and now under Obama, has undertaken a series of almost unprecedented interventions to revive the weakened economy. That skepticism is especially intense among older white Americans. In a Pew Research Center survey this spring, just 23 percent of white seniors said they preferred a larger government that offers more services; 61 percent preferred a smaller government that offers fewer services. Among minorities, the attitude was essentially reversed: 62 percent preferred a larger government and 28 percent a smaller one.

In the states, these contrasting attitudes complicate the struggle to close massive budget deficits. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank, recently calculated that the combined, cumulative shortfall facing state governments — even after adding in federal aid from the 2009 stimulus — increased from $71 billion in 2009 to $137 billion this year and is projected to rise to $144 billion next year.

In the states, these contrasting attitudes complicate the struggle to close massive budget deficits. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank, recently calculated that the combined, cumulative shortfall facing state governments — even after adding in federal aid from the 2009 stimulus — increased from $71 billion in 2009 to $137 billion this year and is projected to rise to $144 billion next year.

To some extent, states wrestle with the decision of whether to slice programs for seniors (such as home health care or other services provided under Medicaid), of those that help children (such as K-12 and higher education, or public health programs for the uninsured). But to a larger extent at the state level, the real choice pits all spending against tax increases.

These debates don’t always follow racial lines. In Arizona, voters this spring approved a three-year sales tax increase that Brewer touted as the only option to avoid even deeper cuts in education and public safety than the state had already approved to close a budget shortfall. “That argument resonated with everybody,” said David Liebowitz, a public-relations consultant who worked on the campaign supporting the increase. “Ironically, our internal polling showed a lot of the support came from senior citizens and older people, which flew in the face of what we generally understand to be true about older folks and tax increases.”

But in many state budget disputes, racial dimensions are not far below the surface. Typically, Republican legislators and governors, most of whom rely primarily on the votes of whites, prefer to close the gaps principally (if not exclusively) by cutting spending, rather than raising taxes. Democrats, who rely more heavily on the votes of minorities, and include more minority legislators in their caucuses, typically prefer to buffer spending cuts by pairing them with tax increases. Even in Arizona, notes Bruce Hernandez, research director of the Behavior Research Center, the “willingness to fund [public programs] has been much stronger within the Hispanic community” than among whites, many of whom “want roads and that’s about it.”

California’s massive and persistent budget shortfalls have forced these issues into particularly sharp relief. As in other states, neither side in the argument has seen much benefit in highlighting the racial connotations of the budget choices.

In a state where minorities represent fully 70 percent of residents under 18, however, those implications are not difficult to discern. Policy makers are grappling with education cutbacks that have left elementary and secondary schools with $17 billion less than they expected over the past two years; tuition increases greater than 30 percent at state colleges and universities over the same period; and proposals from Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to reduce spending on day care and food assistance while raising costs for families receiving public health care. “It’s hitting poor kids and kids of color by far the most severely,” said Ted Lempert, president of the advocacy group Children Now.

The racial dimension of the budget crisis became unusually visible this spring when the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California and other groups sued the Los Angeles Unified School District over layoffs at three middle schools in which most of the students are minorities. In California, as in many states, the least experienced teachers are often assigned to heavily minority schools, which are typically considered the least desirable; state law requires administrators to first lay off teachers with the least seniority. The result was that nearly half of the teachers in two of the schools and nearly three-fourths in the third lost their jobs last year, forcing students to cycle through a parade of substitute teachers. In May, the Los Angeles Superior Court blocked further layoffs at the schools.

Mark Rosenbaum, the Southern California ACLU’s chief counsel, maintains that the school district would not be making such cuts if the school-age population had not tilted so sharply toward minorities. “That’s part and parcel of what is going on,” he says. “This would not be happening to the same degree if it were not families of color and low-income families that are suffering the most.”

Political Implications

These budgetary fights typically line up across partisan lines, with most Democrats on one side and most Republicans on the other. But the competing needs of young minorities and older whites can also create tensions within each party’s coalition, particularly for Democrats. State laws that require teacher layoffs to follow seniority, for instance, tend to draw strong support from heavily Democratic teachers unions but opposition from advocacy groups representing low-income children.

Likewise, the typically generous retirement benefits for state public employees, another Democratic mainstay, may become a target for party reformers looking for revenue to avoid systemic reductions in educational and social services. In California, Education Trust-West, a group that advocates for poor children, says that its constituents are being trampled beneath taxpayer groups that are dead-set against raising taxes and public employee unions that are demanding generous benefits. “The folks who get squeezed are the neediest students and families in the state of California, because you’ve got taxpayer associations on one side and public employee unions and other interests on the other side,” said Arun Ramanathan, the group’s executive director.

In the years ahead, he believes, the state will face increasingly direct trade-offs between investing in young people and supporting state government retirees. “You can’t say our system does a very good job of educating its kids, particularly the high-need students,” Ramanathan says. “And then you have massive pension and health care benefits that were given away in very sweet times to public employee unions. Where in the future are the dollars going to come from to improve the quality of the education system?” he asked. “I think you’re going to see some generational issues down the line.”

Similar questions loom over the federal budget debates. Largely because of Medicare and Social Security, Washington now spends $7 per senior citizen for each $1 it spends per child, according to a 2009 report by Julia Isaacs, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. Even including spending by state and local governments, which fund most education costs, government at all levels still spends more than twice as much per capita on seniors (about $22,000) than on children (about $9,000). To compound the inequity, she says, young people are not only slighted for investment now, they are also likely to face a “tax burden … much higher than current tax rates” to fund the retirement benefits promised to seniors.

The health care bill that Obama drove through Congress this year took a small step toward balancing these scales by reducing the growth of Medicare spending to fund expanded coverage for the uninsured, many of whom are young. But as Simon Rosenberg, president of the Democratic advocacy group NDN, noted at a recent National Journal forum, the administration pushed in the opposite direction this year by protecting other entitlement spending while proposing a freeze in discretionary spending that includes public investments. “[That] would arguably be the inverse of what you would do based on these [demographic] changes,” he argued.

Overall, the tilt toward the elderly over the young in federal priorities remains strong. “Look at where American money is going today. We are investing in the past, not in the future — which is education, research and development, infrastructure,” former Republican Rep. Tom Davis, now director of federal government services at the Deloitte consulting firm, said at the same forum. “We’re General Motors, when you take a look at where the investments in this country are today. And how do you compete globally with that?”

This competition for resources takes place amid a stark divergence in the political preferences of the old and the young. In 2008, Obama won the backing of two-thirds of voters under 29 and fully four-fifths of all minority voters, but he lost a majority of all seniors and nearly three-fifths of white seniors, according to exit polls. The public reaction to Obama’s performance so far suggests that those differences will persist, and possibly widen, in 2010 and even 2012. In Gallup’s weekly tracking poll through mid-July, Obama received positive approval ratings from about two-thirds of nonwhite voters and three-fifths of young people, but only about one-third of whites over 50.

And yet, as Davis and Rosenberg both note, Republicans are generally pushing to retrench entitlement programs that benefit the senior population that is increasingly leaning toward them. Democrats, meanwhile, resist constraints on entitlement costs that could help fund investments in the younger, heavily minority, generation that has become the foundation of their electoral coalition. “It creates an interesting political dynamic, with Republicans calling for cutting entitlements [and thus] cutting their base, and Democrats refusing to cut entitlements and [thus] hurting their base,” Davis says.

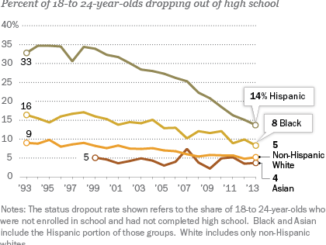

One further irony is that older whites will increasingly depend on the payroll taxes paid by younger minorities to fund Social Security and Medicare benefits. Demographic experts such as the Urban Institute’s Robert Lerman project that the number of whites in the workforce will decline over the coming decades, and that all of the increase in the labor market will come among minorities. Today, only about three-fifths of Hispanic and four-fifths of young black people complete high school, compared with about 90 percent of whites; similarly a much larger share of adult whites (about 30 percent) than blacks (17 percent) or Hispanics (under 13 percent) have obtained college degrees.

“The Baby Boom has a tremendous stake in investing in the education of young Latinos and African-Americans so they will get good jobs and we can tax the daylights out of them to support [the Boomers’] retirement,” Klineberg, the Rice University sociologist, says. “The [racial] gap in achievement has to be narrowed if there’s any serious hope for American competitiveness in the global economy.”

Indeed, Frey projects that if the U.S. does not significantly improve college completion rates for African-Americans and Hispanics, the overall share of American adults with college degrees will decline “very sharply in the next 10 or 15 years.” That’s an ominous trend in an increasingly knowledge-based economy.

“A Titanic Battle”

What’s clear is that demographics aren’t going to provide much relief from these pressures for decades. As the minority population ages, it will make up a steadily increasing share of seniors over the coming decades, Frey notes. But the minority share of the youth population will continue to grow at a comparable pace. So, the chasm between the mostly white senior population and the mostly minority youth — the cultural generation gap — could remain as large as it is today through 2030, before narrowing slowly in the decades thereafter.

If anything, the nation’s evolving demography may wind these tensions even more tightly. While the share of the population represented by young people is expected to stabilize at just under one-fourth, the senior share is projected to steadily rise from about one-eighth today to one-fifth by 2040. By Frey’s projections, that will slowly shrink the working-age population — those who provide the tax base for young people and seniors alike — from about 63 percent of the society now to 57 percent by 2030.

In that world, the generational and racial implications of the choices between tax cuts and spending reductions, and between public spending aimed at the old or the young, could grow increasingly explicit and explosive. Rosenberg isn’t alone in believing that the way the United States sorts through those options will powerfully shape not only its economic but also its social future. “The challenge for us in the next few years is creating a politics of investment during a time of potential austerity to make sure that we’re … funding the future and not the past,” Rosenberg says. “This is going to be a titanic battle not only at the federal level but at the state level as well.”

The article originally appeared on the National Journal on July 14, 2010.