by

Despite having more welcoming policies for immigrants, blue states that once led immigration growth saw some of the steepest decreases in immigrant population last year. The red states of Florida and Texas had the biggest increases, along with Washington state.

New York, Illinois and California had the biggest drops in immigrant population, along with New Jersey, Maryland and Connecticut — losing a combined 206,000 immigrants as Florida and Texas together gained about 170,000. The numbers were released Thursday by the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

It has been a gradual shift from earlier years, when in 2010 California and New York had some of the largest increases in immigration and the biggest drops were in more conservative states such as Arizona and Idaho.

Trade turmoil and spiraling home prices in blue states play a role. The shifts in immigrant population will have an impact on the 1 in 5 U.S. counties where immigration has softened population loss, those with agriculture or meatpacking industries that rely on immigrant labor, and states such as Texas and California where small population changes might cause shifts in political power after the 2020 census.

One obvious factor for the drop in some areas is the high cost of living as housing prices climb in California and other coastal states, making more affordable states a logical choice for new immigrants.

“The whole state of California became unaffordable, along with New York and to some degree even Illinois,” said Randy Capps, research director for U.S. programs at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute.

“There is evidence of a spreading of immigrants into the interior and maybe to prosperous Sun Belt states,” said William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution.

The change also has something do with a decline in Mexican immigration, especially in California and Illinois, and a drop in Chinese property investors in New York as trade tensions increased.

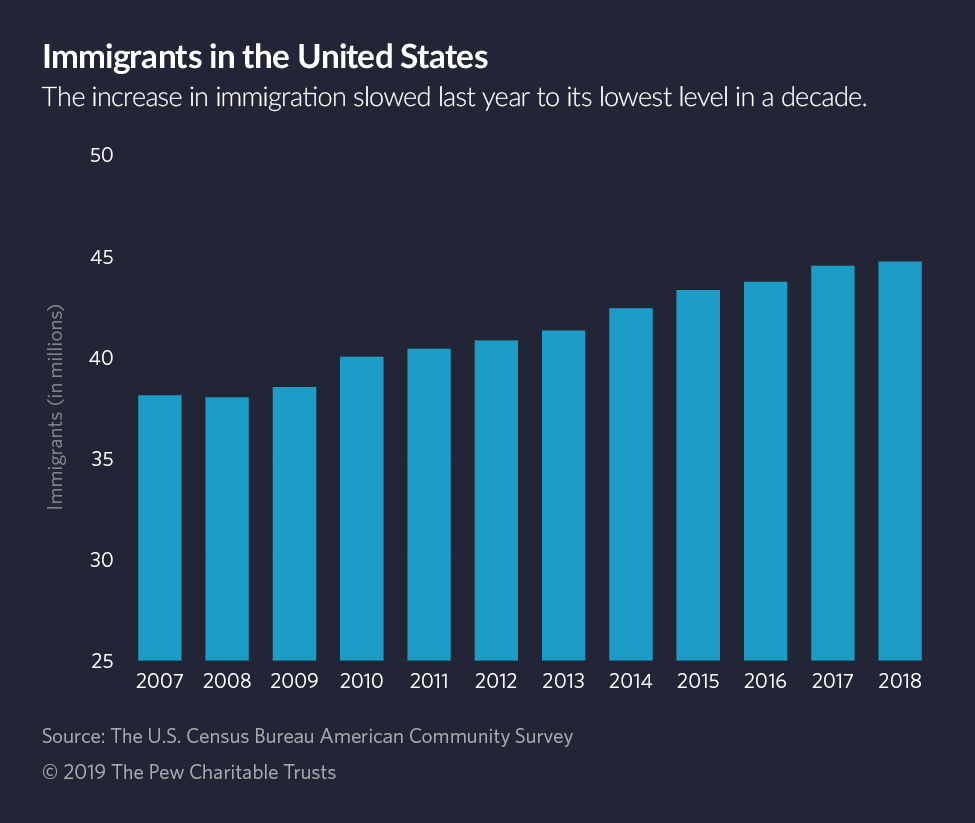

Nationally, immigration grew last year but at the lowest rate in a decade, as a surge in Central Americans at the border was mostly offset by drops in arrivals from Mexico and other countries as cutbacks in both legal and illegal immigration by the Trump administration took hold.

The immigrant population in the United States grew by about 200,000 last year, to about 44.7 million, census figures show. That’s the smallest increase in the number of immigrants since 2008, when the Great Recession caused a rare, small drop in immigration.

The growth of the nation’s immigrant population has been falling off since 2014, when it grew by more than a million.

Guatemalans accounted for almost a quarter of last year’s increase, growing by 48,000 to more than a million. Guatemalans were a large part of the surge in border crossings last year, which swelled even higher this year as more Central Americans fled violence and claimed asylum.

Other groups with large numeric growth: immigrants from Venezuela, where an economic crisis has been driving out the middle class; from India, a source of many workers for high-skill STEM jobs; from Cuba, where immigration has fallen as it gets more difficult; and from war-torn African countries, a source of refugees.

Chinese immigrants in New York were the main factor in that state’s decrease of about 93,000 immigrants, dropping by almost 40,000. Howard Shih, census programs director at the New York chapter of the Asian American Foundation, said Chinese immigrants have been targeted for deportation and thousands have been put in detention outside the state.

Another factor may be a flight of Chinese investors from the New York City housing market after the Chinese government sharply limited permission to invest in the United States. Chinese investors are often rewarded with green cards for themselves and family members under the EB-5 visa program, and China usually gets a majority of those visas, but the number dropped nearly 40% last year, according to federal statistics.

It’s also possible that immigration crackdowns are discouraging some newcomers from responding to the American Community Survey, Capps said. Shih agreed that deportations and detention could be causing immigrants to avoid surveys.

Experts on migration were surprised by the recorded drop of about 9,000 Honduran immigrants. That drop might mean that the survey hasn’t reached all new immigrants in a time of partisan hostility in the United States, Capps said.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection statistics, the number of Honduran families arrested at the border, like those from Guatemala, nearly doubled last year.

Mexicans saw the largest drop among U.S. immigrants, falling about 100,000 to 11.2 million, though Mexicans still comprise the nation’s largest immigrant group. Their numbers fell the most in California, Texas and Illinois but rose in Arizona, Washington state and Oregon.

That might be because of ongoing crackdowns and deportations in Texas, and higher housing costs in California and Illinois, Capps said. Despite a drop in Mexican immigrants, Texas had the second-largest overall increase in immigrant population in the nation, driven by increases in immigration from China, India and Latin Americas countries such as Venezuela and Honduras.

“Texas is the epicenter of deportation now,” Capps said, noting that the state’s anti-sanctuary law — SB4, which requires cities and counties to cooperate with immigration enforcement — has had an impact. “There’s a long-term trend of declining Mexicans; and Guatemalans and other Central Americans moving in to take those jobs, and they’re spreading out around the country.”

Immigration from African countries is also up, especially from Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt and Cameroon. Some are refugees; others make the perilous trip as stowaways to South America and then hike north to apply for asylum at the Mexican border.

For some immigrants fleeing conflict, no journey is too arduous, Capps said. “Some of them are fleeing outright civil war and genocidal conditions. The danger and disorder in Latin America is almost paradise compared to where they left.”

The Cuban immigrant population grew by about 32,000 last year to about 1.3 million, the smallest increase since 2011, when it dropped by about 10,000. Still, it was the largest increase in immigrants for Florida last year.

Cuban immigration has gotten more difficult and secretive since the end of the “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy at the end of the Obama administration in January 2017. Under that policy, Cubans were allowed to stay if they reached shore by boat but were deported if they were caught at sea. The end of that arrangement, combined with Cuban reluctance to give tourist visas, means many Cubans must head for South America or Central America and then travel to the U.S.-Mexican border to claim asylum.

“There are a lot of Cubans who flew to Ecuador, which doesn’t require a visa, and then moved up to the [U.S.] border. For a while the border was open, and they got in,” said Jaime Suchlicki, a Cuban studies scholar and former history professor at the University of Miami.

“Now it’s very tight and they have to stay in Mexico. There are thousands of Cubans right now waiting to cross over,” Suchlicki said.

One Cuban who left the country in 2018 but didn’t manage to get to the United States until 2019 was journalist Yariel Valdés, who won asylum this month after crossing the Mexican border in California and requesting protection because of a Cuban crackdown on independent journalists.

He is still in detention in Louisiana but plans to live with relatives in Florida, where more than three-quarters of Cuban immigrants live. Denied permission to attend a conference abroad, he left Cuba in 2018 on the pretext of visiting relatives in Mexico and never came back, eventually crossing the border in California, said Michael Lavers, a colleague of Valdés when he did work for the Washington Blade this year at the Mexican border.

“I found myself forced to migrate from Cuba since the government kept up a witch hunt against me because of my work as an independent journalist,” he wrote in a statement from detention, in Spanish.

“Even if in recent years migration policies have loosened up, allowing a larger number of Cubans to travel, independent journalists, activists, opponents and others have faced a prohibition against leaving” to participate in international conferences and other events, he wrote. With asylum in the United States, he said, he has “the chance to live in a completely free country and leave that kind of political posturing behind.”

Tim Henderson covers demographics for The Pews’ Stateline.