In 2013, Los Angeles County implemented its own version of a “public option.” It’s delivered change, but not the revolution some advocates want.

by

The dozen elementary- and middle-school students who were practicing calisthenics, before they began a class on healthy eating, surely had no idea they were at the forefront of the debate over the future of health care in America. But the young people who gathered here last week for the Healthy Cooking for Kids session at the Lynwood Family Resource Center are part of what may be the country’s most thorough test in establishing a public competitor to private health insurance.

The Lynwood Center in this predominantly Latino neighborhood southeast of downtown Los Angeles is operated by the L.A. Care Health Plan, the nation’s largest public health-insurance company. L.A. Care was launched in 1997 by the state to manage the health care of Los Angeles County participants in California’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal. But since 2013, it has also sold insurance to the general public through the state insurance exchange established under the Affordable Care Act. In the process, L.A. Care has directly competed with private health insurers for customers, exactly as many Democrats want a “public option” to do nationwide.

“The only income we get is the premium income,” John Baackes, L.A. Care’s chief executive officer, told me. “We don’t get a subsidy; we don’t get any special treatment; we have to go through all the same regulatory hoops that [private insurers] do. So I’m saying, ‘If you want to see what a public option looks like, come take a look.’”

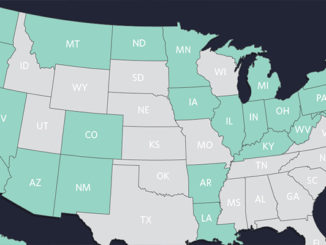

The House passed a public option in the original version of the ACA in fall 2009, but the idea died in the Senate. Now the Democrats most vocally opposing single payer, such as former Vice President Joe Biden and Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado, rely heavily on a public option in their own health-care plans as a way to increase access to coverage and reduce cost.

The experience of L.A. Care shows the possibility of the public option to leverage change, but also the tough choices that loom in implementing the idea. The plan has created a sturdy competitor to private insurers, but it hasn’t had a transformative effect on cost. L.A. Care “ended up being a good and lower-cost option, but it’s not the revolution,” Anthony Wright, the executive director of Health Access California, a consumer-advocacy organization, told me. “It shows both the potential and the limits of a public option.”

L.A. Care’s roots stretch back to California’s decision in the 1990s to move most of its Medicaid population into managed-care programs. To run them, the state authorized counties to establish their own nonprofit, publicly operated health-insurance programs. As Wright told me, the thinking was that since much of the care for these low-income families would come through the public-health system of hospitals and clinics already run at the county level, it made sense to create a public-insurance plan to coordinate with them.

Los Angeles County, the nation’s most populous, was one of several counties in the state that decided to do so. Though L.A. Care is tied to the county government, Baackes told me it operates “definitely at arm’s length” from it, with only one L.A. County supervisor sitting on its board. Managing the medical benefits for Medicaid recipients in L.A. County became a big operation: L.A. Care now coordinates health care for just over 2 million people on Medicaid. After former President Barack Obama signed the ACA into law, L.A. Care won approval from the state to compete for non-Medicaid consumers in the insurance exchanges it established under the law. Today it is the only public-health-insurance plan operating on California’s exchanges, serving about 80,000 consumers. That ranks it first among health-maintenance organizations selling on the exchange in L.A. County, and fourth among insurance plans overall.

The pitch was that L.A. Care could provide continuity of care to people who moved back and forth across that divide: They could keep their same doctors when fluctuations in their income tipped them from Medicaid into the exchanges, or vice versa. “That was why we did it—for continuity,” Baackes said. “The thinking was people who may cross the line and earn a buck more than 138 percent, they’d lose medical eligibility, and if [they] were in the exchange, they could stay with L.A. Care, be eligible for a significant subsidy, and they’d still have access to care.”

As a public plan serving a predominantly low-income population, L.A. Care has developed an unusually holistic approach to health insurance. It has opened six family-resource centers, including the one in Lynwood, and plans to open eight more by the end of 2020. Each center offers dozens of classes each week to promote healthier living—from meditation and stretching to early literacy and domestic-violence counseling. Margaret Coins, who directs the Lynwood Center, told me that more than 800 people pass through it each week. “I have families who have been coming here since day one,” said Coins, who has worked at the Lynwood facility since it first opened in 2009.

L.A. Care is now moving toward more comprehensive services. It wants to coordinate more closely with other social-service agencies to ensure that customers are enrolling in benefits that they’re eligible for, from housing assistance to food stamps. It is training a corps of “community health workers” who will coordinate care for the minority of plan members with the most complex medical needs (the people who also generate the most expenses for any health insurer).

L.A. Care also interacts with medical providers in an unconventional way. Rather than paying providers for each visit or procedure (what’s known as fee-for-service), it offers them a fixed sum to cover all the health-care needs of each patient. That reduces the incentive for providers to maximize visits from patients and instead, as Baackes put it, encourages them to ask, “What’s the most efficient way to ensure they get the highest quality?”

For all these reasons, outside observers generally praise L.A. Care as a worthy model. Laurel Lucia, the health-care program director at UC Berkeley’s Labor Center, said the plan has demonstrated that a public option can effectively coexist and compete with private insurers. But, like Wright, she notes that the plan’s effect on medical costs has been evolutionary, not revolutionary. Not until this year was L.A. Care offering the lowest premiums on the ACA exchanges in L.A. County, and Baackes said another plan may be slightly less expensive next year.

That dynamic points to what could be the most contentious issues for Democrats in any future attempt to create a nationwide public option. Many health reformers want a public option to reimburse doctors and hospitals at the rates paid by Medicare, which are much lower than what private insurers pay. Lucia told me that doing so would offer the best chance of significantly reducing national health-care costs.

“If there could be an L.A. Care in every county … that would be an improvement, but it certainly wouldn’t be transforming our health-care system overall,” she said. “A national public option that pays providers Medicare rates would have much more dramatic effects on the overall health-care system.”

But many private insurance companies, with some reason, fear that a public option operating on such a reimbursement system would set the country on a path to a government-run, single-payer system. If a public option paid providers that much less, private insurers reason, it could charge much less than they do in premiums and ultimately siphon away most of the insurance market.

Baackes largely seconds the concern that a public option paying Medicare rates would undermine the private insurance market. “If it was set up that way, I’d be afraid of it too,” he said. Baackes is “making it my mission” to convince the private-insurance industry that it can coexist with a public option. But his vision of the public option, rooted in his experience with L.A. Care, is very different from the nationalized plan envisioned by many liberals. It would involve local plans established at the state, county, or city level that each negotiates its own agreements (and reimbursement schemes) with local providers. “There is something to be said about localizing them as much as possible, because then they are designed around local conditions,” he told me.

That model probably wouldn’t promise enough change for those who see the public option as the only opportunity, short of a single-payer system, to fundamentally transform the health-care system. But it might thread the political needle of offering enough change to satisfy reformers without provoking scorched-earth resistance from insurance companies and medical providers (not to mention some upper-middle-income patients who fear losing access to high-end doctors and hospitals).

Few Democrats today may want to hear it, but the compromises that led to the ACA, executed by Obama and his then–chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, are what staved off a full-scale medical-industry uprising against the bill. And that was a large reason that Obama became the first president to pass legislation moving the nation toward universal health care, after Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, and Bill Clinton all tried and failed to do so. L.A. Care’s growing web of services for the families most in need may look like modest change compared with the calls from Sanders and others for a “revolution” in health care. But the steady gains evident in Lynwood may offer a more revealing preview of what the next Democratic president and Congress could likely achieve.