by Richard Whitmire

The headwinds that low-income students face as they try to earn college degrees have reached “critical level,” warned the director of the closely watched Pell Institute’s “Indicators of Higher Education Equity” report released last week.

“There is a large disconnect between the resources required for students to enter and complete college and the assistance and public support they get,” said Margaret Cahalan, director of the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, in a phone conference with reporters on Tuesday.

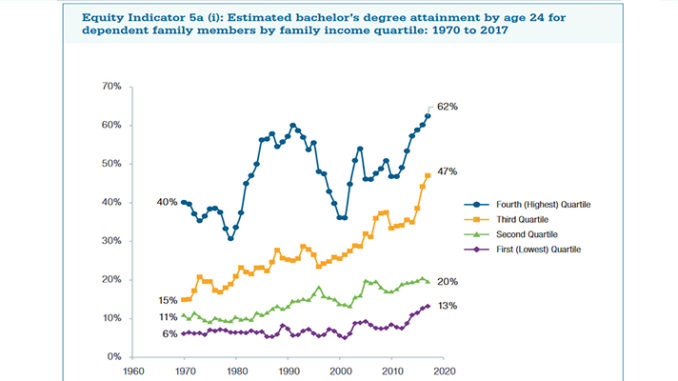

The report, which focuses on equity issues in higher education, warns of a broadening gap between low- and high-income families. Students entering college from low-income families who are also the first in their family to go on to higher education have a 21 percent chance of earning a bachelor’s degree in six years. Among students from higher-income families, 57 percent will earn degrees.

The inequities laid out in the Pell study echo the recent Born to Win, Schooled to Lose report from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. The bottom line of that report: In the United States, it’s better to be rich than smart. Children with low test scores from high-income families have a 71 percent chance of being affluent adults by the age of 25, compared with only a 31 percent chance for poor children with high test scores.

Both reports focus on the macro data, which are grim. There may, however, be more reason for hope than is found in either report. In my recent book published by The 74, The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. I document several developments that promise a brighter future for low-income college-goers.

The reasons for the widening gaps between have and have-not families involve access to higher education. Children from low-income families attend high schools that often fail to prepare them for college. Those same schools lack counselors trained to guide them into colleges where they are likely to earn degrees.

Once in college, they struggle to meet the financial demands, and even if they earn a degree, they leave college with crippling debt. In the 1990s, roughly half of those earning a bachelor’s took out student loans. By 2016, 7 out of 10 students took out loans. The average amount of debt for graduating seniors: $30,000, according to Pell.

The elation among Morehouse College graduates when their billionaire commencement speaker announced last week that he was wiping out their student loans said it all — it was a life-changing gesture.

In part, those loans are driven by lagging public financing. In the mid-1970s, federal Pell Grants that help low-income students covered two-thirds of average college costs. By 2017, those grants covered only 25 percent.

That put more pressure on families and students, leading to one unexpected development that years ago would have seemed improbable — food banks on college campuses for students who have to choose between textbooks and meals.

“For many college students, the decline in Pell Grants relative to college costs and growing family income inequality in the United States means a rise in food, housing, transportation and basic-needs insecurity, and the need to assume large debt and to work long hours,” said Cahalan. “Too many work hours and basic-needs insecurity creates insurmountable obstacles for many students and negative impacts on the realistic opportunity these students have to succeed in college.”

But is the higher education equity situation uniformly grim? I argue that three developments offer considerable hope for the future.

First: The large, high-performing “no excuses” charter school networks operating mostly in big cities have forged new pathways for their alumni to earn degrees. Depending on the network, the percentage of their graduates earning bachelor’s degrees at the six-year mark is between two and four times what would be expected.

Uncommon Schools, which started in Newark, show college success rate trends that indicate their alumni will soon start earning degrees at the same rate as students from wealthy families. Most encouraging: Several traditional school districts, including New York City, Miami and Newark, have signed on to collaborations with the KIPP charter network to start adopting some of the lessons learned by charters to boost college success.

Second: A growing number of philanthropy-funded organizations — groups such as the College Advising Corps — now offer smart, data-driven college counseling to students in high schools where that is lacking. The key is not just finding the best colleges for students, but steering them away from universities with poor graduation records.

Third: Groups such as the American Talent Initiative that work with universities to boost the number of low-income students who enroll — and ensure they earn degrees — are starting to see progress.

Are these promising efforts enough to change the shape of the national data that look so grim in these two reports? Not yet, but the potential is there.

Education writer Richard Whitmire is the author of several books, most recently “The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.” Whitmire is a member of the Journalism Advisory Board of The 74.

Richard Whitmire is the author of several books, most recently “The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.” Whitmire is a member of the Journalism Advisory Board of The 74.

Disclosure: The 74’s CEO, Stephen Cockrell, served as director of external impact for the KIPP Foundation from 2015 to 2019. He played no part in the reporting or editing of this story.