by David Wessel, Senior Fellow & Director, Hutchins Center at the Brookings Institution1

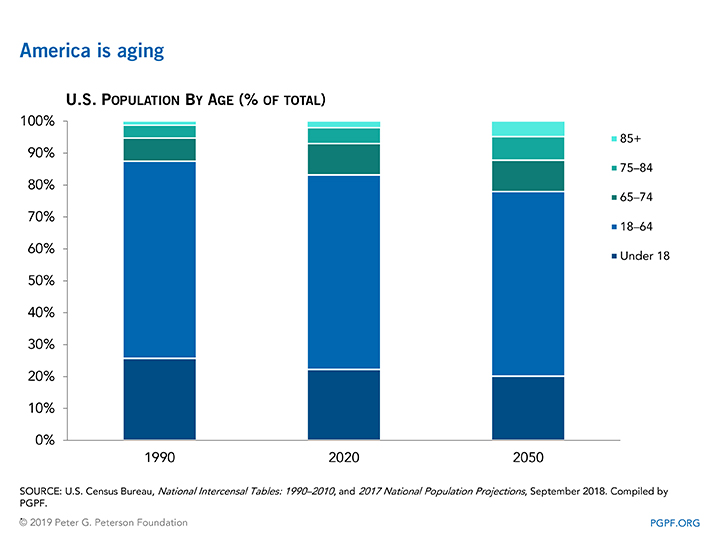

The U.S. is in the midst of a long transition to an older society. Just 10 years ago, the share of the elderly in the population was 13 percent. Today, it is about 16 percent and the Pew Research Center projects that by 2050, it will be 22 percent.

Today, there are 45 percent more children under age 18 than there are people 65 and older; well before 2050, adults 65 and over will outnumber children. And there will be two-and-a-half times as many people 85 or older as there are today.

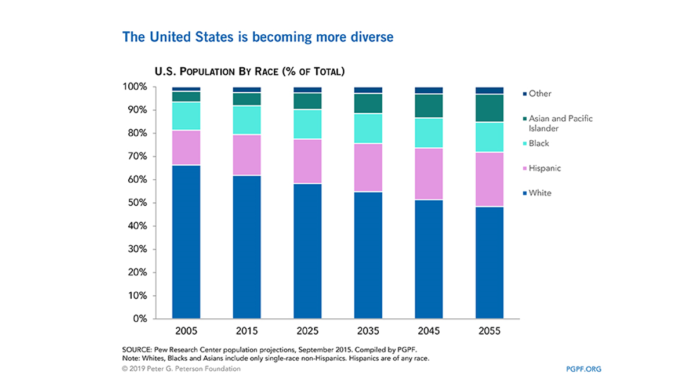

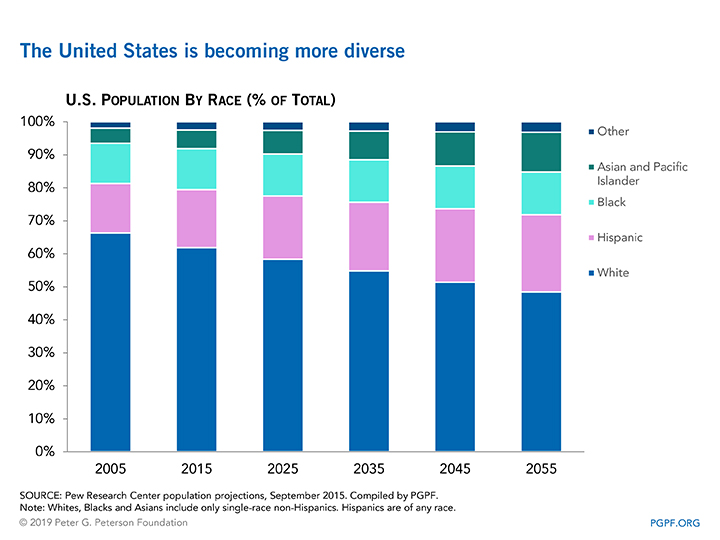

America will also be more diverse. By 2050, the Census Bureau projects the number of non-Hispanic whites will be falling, the number of African Americans will have grown by roughly 30 percent, the number of Hispanics by 60 percent and the number of Asian Americans will have more than doubled.

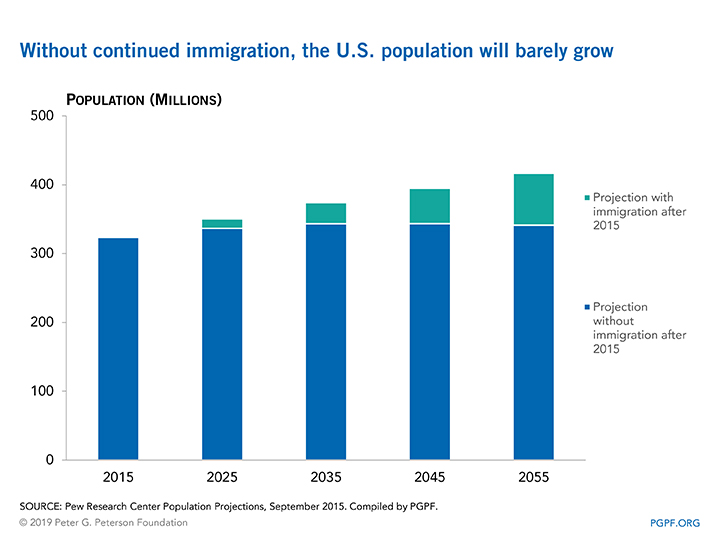

Immigrants and their children account for 26 percent of the U.S. population today; by 2050 that’ll be 34 percent, Pew projects. That, of course, depends on what happens to U.S. immigration policy between now and then. Without continued immigration, the U.S. population will barely be growing at all in 2050 as the number of births roughly equals the number of deaths.

With that changing demography as a backdrop, the US 2050 project examines the economic forces and trends that will determine American living standards three decades from now. Over long stretches of time, the pace at which the economy grows reflects the pace at which productivity — output per hour of work — increases and the pace at which the workforce grows. More people working — higher rates of labor force participation among natives or more immigrant workers — will yield faster economic growth. More investments in people — in education and health care, particularly for today’s children — will yield faster growth in productivity and in average income per person. How well typical American families live will depend on how the fruits of prosperity are shared — how much go to the very top, how much go to the middle class and how much go to the poor — and on what happens to the racial and ethnic disparities that mark today’s America.

The fiscal health of the U.S. government also depends on trends in aging and health, productivity growth, labor force participation and immigration. The more tax-paying workers, the easier it will be to pay for retirement and health benefits promised to the growing number of elderly people. The better educated and healthier the workforce, the faster productivity is likely to grow: The faster productivity grows, the faster wages and profits will rise, giving the nation more resources to pay for those retirement and health benefits for the old while delivering rising living standards for the working-age population and their children. Understanding implications of aging and the increasing diversity of the U.S. — from disparities in enrollment in early childhood education to differences in college-going by race to patterns of care-giving for the elderly — is crucial to making wise policy decisions on revenues (how much to tax, who to tax, what to tax) and on spending (how best to change retirement, health and other benefits, and where to direct public investment.)

Extrapolating from the recent past will not suffice. Focusing only on averages in an increasingly diverse society will be misleading. The US 2050 papers provide much-needed evidence and analysis on a very wide variety of topics, and point the way towards further research needed as the nation prepares for the future. The following draws from a selection of the US 2050 papers. See the Appendix for summaries of all of them.

The size and composition of tomorrow’s labor force depends on how many children are born in the U.S. and how many people immigrate to the U.S.

The U.S. long has had a higher fertility rate than other developed countries, averaging a bit above 2 children per woman from 1990 to 2007, close to the rate needed to keep the population steady from one generation to the next. But fertility began declining in the Great Recession, and has continued to drift down ever since, hitting a historically low rate of 1.8 in 2017. A key question is whether this decline in fertility in the U.S. is temporary or permanent. Alicia Munnell, Anqi Chen and Geoffrey Sanzenbacher of Boston College find that states that experienced larger increases in unemployment during the Great Recession had larger declines in fertility rates, suggesting that the decline might be temporary. But they note that the fertility rate has continued to decline despite the economic recovery, and conclude that the fertility rate is being driven by factors other than the ups and downs of the economy.

One indicator of future fertility patterns is how many children women say they plan to have. Alison Gemmill of Stony Brook University and Caroline Sten Hartnett of the University of Southern Carolina note that the average age of having a first child has been rising over the past decade, and women continue to report that they intend to have more than two children on average. These factors suggest that women may be delaying having children rather than foregoing parenthood. On the other hand, the fertility intentions of 20- to 24-year old women have declined in recent years, particularly among Hispanic, black, and foreign-born women, whose fertility rates are historically higher than those of non-Hispanic white women. Immigration is less likely to boost fertility going forward, both because of declines in immigration from high-fertility countries and because of declines in fertility in those countries.

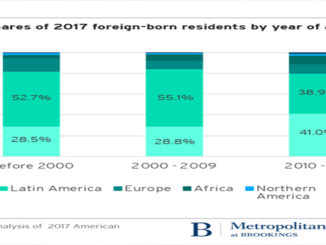

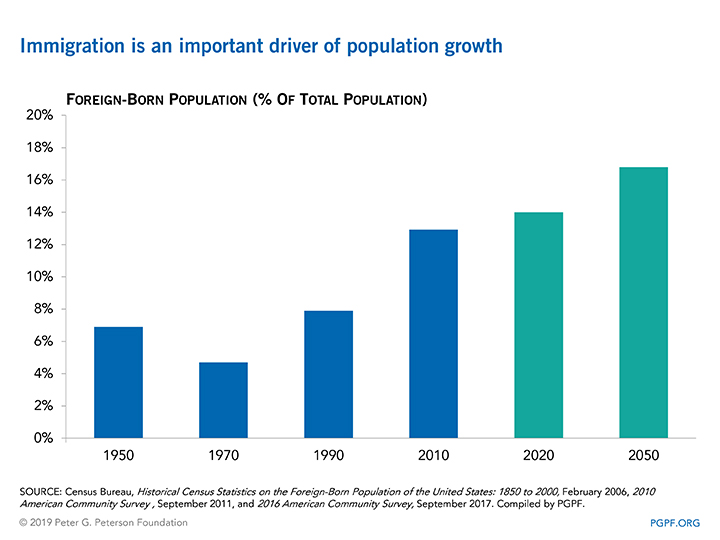

Immigration has been an important driver of population growth since the rewrite of the nation’s immigration laws in 1965, both because of the climbing number of immigrants and because immigrants’ fertility is higher, on average, than the fertility of native-born women. Immigrants comprise about 14 percent of the U.S. population today versus 5 percent in 1965; Pew Research Center attributes 55 percent of the U.S. population growth since 1965 to immigrants, their children and grandchildren. Over the past half century, the origins of immigrants to the U.S. has changed: fewer have been European whites; more have been Hispanic or, increasingly, Asian. Although there are still many more people living in the U.S. who were born in Mexico than were born in China and India combined, Pew says the annual flow of new immigrants from Asia surpassed that of Hispanics in 2009.

The changing composition of the flow of immigrants to the U.S. reflects, in part, the different economic conditions in their home countries, but Jennifer Sciubba of Rhodes College argues that changes in U.S. immigration policies are a more important factor. Immigration from India and China picked up in the 1990s because the H1-B visa program provided an entry ramp for high-skilled foreigners. Immigration from Mexico slowed between 2000 and 2007, partly because enforcement and monitoring at the border intensified after 9/11. Still, immigration from Mexico tends to go up when the economy there is worse than it is here and tends to fall when the U.S. economy sags, as when the mid-2000s housing bust reduced demand for construction workers.

Most immigrants come to the U.S. in search of a better life, but the effect of immigration on workers who are already here remains the subject of much public — and some academic — controversy. Vasil Yasenov of the University of California at Berkeley documents that, since 2000, immigrants have tended to be either low-wage, less-skilled workers or high-wage, higher-skill workers with relatively few immigrants in the middle. He finds that while immigration slightly reduces the wages of low-wage workers who are already here, it slightly increases the wages of higher-income workers because higher-skill immigrants complement, rather than substitute for, higher-skill workers who are already here. He concludes that immigration has not had a big role in the increase in income inequality in the U.S. though it may have widened the gap between the very bottom and the very top.

Today’s children are tomorrow’s workers so investments in children today will pay off in higher productivity in the future

There is mounting and convincing evidence that investing in children’s education and health — even while they’re still in in the womb — affects their future earnings, health and other outcomes. Investments targeted at children in low-income families have a particularly powerful payoff. Papers in the US 2050 project add to this body of research.

Forty percent of births in the U.S. today are to women who are not married. Compared with children who are raised in cohabiting or single-parent families, those who grow up with stable, married parents fare better in terms of health and behavior in childhood, achievement in adolescence and as adults. These differences in family structure are contributing to increases in income inequality later in life, say Orestes Hastings of Colorado State University and Daniel Schneider of the University of California at Berkeley. Using data on more than 37,000 households, they document that married parents invest more in childcare, schooling and enrichment, in part because they tend to have higher incomes. Married parents spent $320 more per child per year than cohabiting parents and $276 more than single parents. Comparing families with similar incomes, the authors find that cohabiters invest substantially less in their children than married couples, perhaps because they are less committed to a long-term relationship. Differences between families with married and cohabiting parents are more pronounced among whites than among blacks and Hispanics. Strikingly, single parents invest more than married parents of similar incomes do, in part because they spend more on childcare. The authors suggest that increasing the economic resources of single parents, who tend to have lower incomes, through the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or increases in the minimum wage could benefit their children. They are skeptical about the benefits of promoting marriage among cohabiting parents — partners who are committed to a long-term relationship already are more prone to be married — and instead suggest increased public investment in children through schools and health and nutrition programs to reduce the inequality caused by different family structures.

The rising share of children born to women who aren’t married means an increase in the number of non-resident fathers, some of whom provide financial support to their children and some of whom don’t. These men are disproportionately non-white, lack college degrees and live outside urban areas — and were particularly hard hit by the Great Recession. Ronald Mincy and Hyunjoon Um of Columbia University find that only about 30 percent of these men meet their state-mandated child support obligations on a regular basis. One big reason: They don’t earn very much. About 55 percent of vulnerable non-resident fathers earn less than $20,000 a year and more than two-thirds of them don’t have enough income to meet basic needs and state-required child support payments. A greater share of Hispanic non-resident fathers is financially vulnerable than are shares of blacks and non-Hispanic whites. Mincy and Um argue for policies that would make it easier for non-resident fathers to meet their child support obligations, including more lenient state guidelines for calculating child support and increasing the EITC for non-custodial parents.

The benefits of high quality early-childhood education have long drawn attention from academics and policymakers. Erica Greenberg, Victoria Rosenboom and Gina Adams of the Urban Institute see early-childhood programs as particularly valuable to the children of immigrants, who account for one in four young children in the U.S. and will account for a growing share of the nation’s workforce in years ahead. But immigrant parents are less likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to enroll their children in formal early-childhood programs. Research shows that barriers to access rather than preferences for family care account for this gap. Still, children of immigrants are nearly as likely to participate in Head Start and public school kindergartens, so these programs are helping to close the access gap.

More than one-quarter of today’s children — tomorrow’s workforce — attend elementary schools in neighborhoods in which 20 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. Katie Vinopal of Ohio State University and Taryn Morrissey of American University find that children in high-poverty neighborhoods (those in which more than 20 percent of the people are poor) enter kindergarten almost one year behind in reading and math relative to their peers in lower-poverty neighborhoods. Reading and math scores of children in high-poverty communities increase substantially faster — 26 percent for math and 8 percent for reading — in kindergarten, but this isn’t enough to close the gap that opens up in the pre-K years. The negative effects of going to school in a high-poverty neighborhood are larger for black children than for their non-white peers. In short, achievement gaps by neighborhood resources are present before kindergarten, shrink during the kindergarten year, but then widen the year following, and later remain relatively consistent in the first years of elementary school. The authors see the results as evidence that reducing neighborhood economic segregation is key to narrowing achievement gaps.

Robert Bozick of RAND Corporation and Narayan Sastry of the University of Michigan find that children with depression, anxiety, ADHD, anti-social behavior and other mental health issues are less likely to complete high school, less likely to enroll in college and more dependent on their parents as adults than their peers who don’t exhibit such behaviors. Consequently, they see benefits in more and better treatment of mental health issues in children. In contrast, Bozick and Sastry find that children with asthma or who are obese do not suffer similar long-term economic consequences, at least through their early adult years.

Good jobs in 2050 will demand more educated workers, and less-educated workers will be at risk of being left behind

The gap between winners and losers in the labor market has been growing over time, and is increasingly the subject of public concern and academic inquiry. The drivers of this widening inequality are many — the rising power of employers and the waning power of unions, the intensifying competition from globalization, the growing demand for workers with skills and education outstripping the supply of such workers.

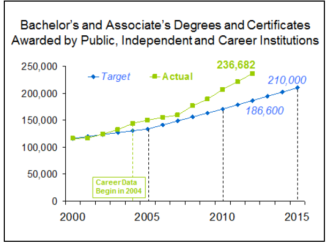

Today about 10 percent of U.S. adults hold two-year college degrees and just over a third hold four-year degrees. Whites and Asian Americans are more likely to have bachelor’s degrees than blacks or Hispanics. Since 2000 a growing share of adults in each group has earned a four-year degree. Starting with projections of slower population growth and an increasing share of the population that is non-white, Harry Holzer of Georgetown University looks ahead to 2050 and sees a more slowly growing labor force that is likely to be no better educated than today’s. Because blacks and Hispanics are less likely to go to college, but will represent a growing share of the population, Holzer projects that the overall fraction of the U.S. workforce with a college degree will fall. If there is no further increase in college graduation among non-whites, he foresees a drop of 2.3 percentage points in adults with bachelor’s degrees and a less than half a percentage point drop in those with two-year degrees. But if the share of non-whites who go to college continues to increase, the decline will be much smaller — 0.7 percentage points — for four-year degrees; the share of the population with two-year degrees will be about the same. Policies that make work pay, such as the EITC, and those that increase attachment to the labor force, such as paid family leave, could help mitigate the effects of slowing population growth by increasing the share of adults who want to work.

On the demand side, Holzer anticipates that automation will require workers to adapt to maintain their old jobs or find new ones that pay reasonably well. Technology also is likely to enable employers and workers to turn to alternative staffing arrangements. Some arrangements will offer workers greater flexibility and choice; others will be imposed on them and likely will reduce their training and earnings growth. Public policy should, he says, both encourage workers and employers to increase training and education, and expand policies that aid workers who are displaced or otherwise can’t quickly adapt to the changing demands of the job market.

Older African American women are particularly vulnerable to technology-driven changes in the job market, says Chandra Childers of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. African American women have historically been more likely to work than their white counterparts and have been significant breadwinners in their families. They have tended to work in a small number of occupations with low pay, poor working conditions and few demands for formal education, including household work and child- and elder-care. Using projections for occupations most susceptible to automation and digitalization, as well as data on the occupations in which African American women are most likely to work, Childers finds automation has had little effect on employment or working hours over the past 15 years. But the future looks different: African American women disproportionately work in low-paying occupations that are likely to be automated over the next decade or two. Many of them lack the training or educational credentials required for higher paying jobs. Without targeted retraining programs or expanded access to college, African American women will be at an increasing disadvantage in the labor market over the next few decades, Childers concludes.

There will be more old people — and someone will need to care for them

As the number of very old people grow — the result of the aging of the large Baby Boom Generation born between 1946 and 1964 and generally lengthening life expectancies — more of them will require care from others.

Today about 10 million Americans over age 65 rely on unpaid care from family and friends. This number is certain to grow over the next few decades, which has potentially large effects on both the supply of workers in the economy and on the incomes of those who don’t have paying jobs because they’re providing unpaid care for others. Stipica Mudrazija of the Urban Institute finds that caregivers are about 9 percentage points less likely to be employed than demographically similar people who don’t provide care. And among those who do have paying jobs, they work 3.9 fewer hours a week than their peers who aren’t caregivers. He estimates that today’s caregivers are sacrificing about $67 billion a year in wages, and projects that will more than double by 2050. Mudrazija finds that caregiving responsibilities depress labor force participation more for college-educated minorities than for others.

Today 25 percent of all caregivers of the elderly are their children. While parents of the baby boomers had three children per household on average, the boomers themselves have had only two. The ratio of individuals over age 85 to those in peak caregiving years of 45–64 is projected to increase from 1-to-7 today to 1-to-3 by 2050. That is likely to increase the demand for institutional care. Gal Wettstein and Alice Zulkarnain of Boston College estimate that among people over age 50, having one fewer child increases the probability of spending a night in a nursing home over a two-year period from 10.7 percent to 12.4 percent. That increase of 1.7 percentage points is similar in magnitude to the effect of having self-reported poor health or being 10 years older. Looking ahead to 2050, they project that the decline in fertility alone will increase the demand for institutional care by 8.6 percent. Combining lower fertility and the tripling of the population over age 85, they estimate the demand for institutional care will be about 3.3 times today’s demand — with obvious implications for the long-term care industry and the Medicaid program, which foots much of the bill for long-term care.

Many of those paid to care for the elderly are immigrants. Kristin Butcher of Wellesley College and Tara Watson of Williams College identify eight occupations that may help the elderly age at home as opposed to in institutions, such as nursing aides and housekeepers. They predict the share of the workforce in such jobs will grow from about 8 percent today to 12 percent in 2050, implying 2.2 million more foreign-born caregivers. The authors calculate that a 42 million “target” of foreign-born workers will be needed in 2050, which is substantially higher than the 29 or 30 million immigrants that would be in the U.S. in 2050 if Census projections are correct.

Of course, the healthier the elderly are, the less care they’ll need. Noting the rising cost of government disability benefits, Bryan Tysinger and Dana Goldman of the University of Southern California estimate the cost of various chronic diseases to disability benefit programs and, thus, the potential savings from better prevention. They find, for instance, that eliminating hypertension altogether would save the government $3.5 trillion between 2018 and 2050 through increased tax revenues (because there are more taxpaying workers) and reduced spending on disability benefits, Supplemental Social Security Income for the neediest elderly and Medicare (which offsets increased spending on Medicaid and Social Security because of increased longevity.) The authors argue for increasing efforts at preventing disease rather than waiting to treat it once it develops, but caution that even wiping out chronic diseases altogether would not put federal government retirement and health benefits on a financially sustainable course.

And financing the retirement of the growing ranks of the elderly will be a challenge

Older Americans who are no longer working live mainly on their savings, employer-provided pensions and Social Security. Financing the retirement of the increasing number of retirees poses challenges for the federal government and to individuals, and there are wide gaps between those who are likely to have saved enough for a comfortable retirement and those who have not.

By 2050, the millennials — those born between 1981 and 1996 — will be nearing retirement age. William Gale of the Brookings Institution, Hilary Gelfond of Harvard University and Jason Fichtner of Johns Hopkins University caution that, as a whole, the Millennial Generation may not have saved enough for a standard of living in retirement similar to the one they had during their working years. Compared to other generations, millennials have some advantages: more education (and, thus, higher wages) and longer working lives, and those could lead to more savings. But millennials also face stiff headwinds: they entered the job market during the Great Recession, which could have long-lasting effects on their earnings. They are marrying and having children at older ages. The job market is changing with fewer traditional employer-employee relationships and more contingent gig economy jobs, which typically offer less generous (if any) retirement benefits. And there has been a continuing shift away from defined-benefit to defined-contribution retirement schemes. All of those factors put more responsibility to save on the shoulders of individuals. Noting that a greater share of the millennial cohort is non-white, the authors highlight that minority households, in general, tend to have less wealth than whites of similar income, education and marital status, which suggests lower savings from which to draw in retirement. A black household has, on average, a net worth of $124,000 less than a white household does, even after adjusting for income and education — and the black-white wealth gap may be increasing.

Barbara Butrica of the Urban Institute also looks at how Generation X and early millennials (currently between 35 and 54) will fare in retirement in 2050 (when they are between 65 and 84) compared to their current economic situations and compared to current retirees. Using a large-scale microsimulation model, she finds that many genX-ers and millennials will find it difficult to maintain or improve their economic circumstances as they age. Those without any college, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics will have an especially difficult time. However, because they will work later in life and because women’s earnings will be higher, genX-ers and millennials are projected to have somewhat higher income in retirement, on average, than current retirees. Retirement outcomes are projected to improve slightly for Hispanics and dramatically for Asian Americans and Native Americans. There will, however, will be greater inequality in retirement among the younger generation, and their retirement income will represent a smaller fraction of their earnings than today’s retirees. The disparities are stark. For instance, 89 percent of genX and millennial college graduates will be offered workplace retirement benefits during their lifetimes, but only 52 percent of those without high school diplomas will. Less than half of all Hispanics are projected to ever participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan versus more than three-quarters of non-Hispanic whites and two-thirds of non-Hispanic blacks. Future retirees without college educations, with little lifetime labor force attachment and with relatively low lifetime earnings will fare relatively poorly in retirement, she finds.

College graduates, in general, earn more than their peers who didn’t go to college, and thus are likely to be better off in retirement. Also using a large-scale microsimulation model, Damir Cosic of the Urban Institute finds that the impact on lifetime earnings varies significantly across race and gender, and those differences translate into disparities in retirement income. Specifically, white women who graduated from college earned 26 percent more in 2010 than those who didn’t, but the college-going premium for black women was just 19 percent. For white men, the college premium was 15 percent; for black men, it was only 11 percent. Projecting income in retirement, however, suggests that the gender and racial gaps are narrowed somewhat because Social Security benefits are distributed more equally than the lifetime earnings on which they are based. Cosic also finds that race-based wage discrimination among college-educated workers leads to large losses in lifetime earnings for blacks. Over a working life, black men lose an estimated $1,000,000 in total earnings, and black women lose an estimated $700,000 to wage discrimination. These differences have significant implications for the distribution of retirement income in 2050, and suggest there is room for policymakers to combat wage discrimination.

Melissa M. Favreault of the Urban Institute looks at inequality through a different lens: The differences in the incidence of disability among adults older than age 50 by socio-economic status and the implications for Social Security and Medicare. She finds that people with less education and lower earnings spend fewer years receiving benefits due to shorter life expectancies, and that a greater share of their total benefits are paid during spells of severe disability (when Medicare spending on them is relatively high.) For those with more education and higher earnings, in contrast, needs are less intensive and spread over a much longer period because they tend to live longer and spend more years in reasonably good health. Looking at Social Security and Medicare benefits combined, Favreault projects that the least educated, lowest income groups will receive half their lifetime benefits during periods of disability (and thus are more dependent on Medicare) while the more educated and wealthier will receive a quarter of their lifetime benefits during periods of disability (and are more dependent on Social Security.) This diversity in beneficiaries’ experiences has important implications for how policymakers approach changes to put the Social Security and Medicare programs on a fiscally sustainable path. She specifically suggests that changes be designed to maintain and even enhance the incentives to work later in life for those who are able while maintaining protections for those whose disabilities leave them economically vulnerable.

It is not only low-income families who are strained financially — both during their working years and in retirement. A decade after the Great Recession, almost 30 percent of households earning between $50,000 and $75,000 and 20 percent of those with annual income in the $75,000 to $100,000 range are financially fragile according to Andrea Hasler and Annamaria Lusardi of The George Washington University. They would struggle to come up with $2,000 to meet emergency needs in 30 days. These households do own assets including homes, retirement and college savings accounts, but Hasler and Lusardi find that households with assets are more likely to have a lot of debt and to pay high interest rates and other fees. Because financially fragile households have low levels of financial literacy, they are less able to manage their assets and debt and are much less likely to plan for retirement. The authors suggest that a significant number of middle class households are ill prepared for a shock — let alone able to save for the long term — suggesting the need for more incentives to encourage precautionary saving.

All these changes present challenges to a polarized political system that deals poorly with long-term challenges

Today’s Congress is marked by intense polarization, hyper-partisanship and gridlock. Notwithstanding these challenges, Congress will need to address several big and complex issues over the next few decades — the increasing diversity of the population, looming fiscal challenges facing the federal government, widespread automation and technological change that will change the job market, climate change, global pressures and more. The extent to which Congress will be able to respond to these challenges effectively will depend on whether politics in the U.S. will be polarized or pluralized, and whether the U.S. government will operate in a Hamiltonian (a strong presidential-led government) or a Madisonian (a stronger role for Congress vis-à-vis the president) manner, says Daniel Stid of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The intersection of these two dimensions of uncertainty generates four plausible scenarios for how Congress — and American politics and government more broadly — might function in 2050. He concludes that electoral outcomes, the strategy and messages of political candidates, and the approach that presidential candidates use in building their electoral coalitions will determine where politics falls along the polarized-pluralized spectrum. Further, a focus on foreign and national security will push the U.S. towards a Hamiltonian government, whereas policy focus on popular programs such as social insurance and healthcare would push towards a more Madisonian government.

The composition of the political leadership is likely to change as the population does. Danielle Lemi of Southern Methodist University finds, through interviews, that multiracial legislators may serve as bridges between groups by selectively highlighting their identifies and thus may enjoy an advantage in building coalitions, but also may confront hostility from some groups with which they identify.

Sarah Bryner and Grace Haley of the Center for Responsive Politics document that while Democrats ran more female candidates and candidates of color than Republicans in the 2018 midterms, their candidate pool was still less diverse than their electorate, particularly in competitive races. Looking at fundraising in particular, the authors find that being a woman increased total fundraising, controlling for factors such as incumbency, district income, and competiveness of a general election. However, being African-American decreased total fundraising. Much of the increase in female fundraising in 2018 was driven by female candidates raising a disproportionate amount of money from female donors. Although the 116th Congress is much more diverse than its predecessors, the authors argue that there remain significant barriers to disadvantaged groups in running for office.

These and other papers commissioned for the US 2050 project are like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. They provide clues to the ways the U.S. population will change in the next three decades and insights into the policies and investments that need to be considered today to produce higher living standards in a society that is older and much more diverse than today’s. We don’t have all the pieces of the puzzle yet so we can’t see the complete picture. The future is always uncertain. There is more work to be done, but we know more because of the US 2050 papers.

1 Sage Belz, Stephanie Cencula, Jeffrey Cheng, Vivien Lee, Michael Ng, Finn Schuele, and Louise Sheiner, all of the Hutchins Center at Brookings, contributed to this report.