by Albert Cheng, Michael B. Henderson, Paul E. Peterson and Martin R. West

Results from the 2018 EdNextPoll

Education’s political landscape has shifted dramatically over the past year. To the consternation of most school-district officials, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos used the bully pulpit to promote charter schools, vouchers, and tax credits for private-school scholarships. To the distress of teachers unions, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an Illinois law requiring government workers who elect not to become union members to pay representation fees. To the chagrin of civil-rights groups, the U.S. Department of Education said that it was reviewing a letter sent to school districts by the Obama administration informing them that they were at risk of incurring a civil-rights violation if students of color were suspended or expelled more often than their peers. To the relief of Common Core enthusiasts, the politically charged debate over the standards moved to the back burner. And to the dismay of parents, teachers, and policymakers across the political spectrum, students demonstrated almost no gains in reading and math on the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) over the 2015 test.

All these events were consequential, but none penetrated into the thinking of the American public as sharply as did teacher strikes in six southern and western states. Those walkouts seem to have lent new urgency to teacher demands for salary raises and increased financial support for schools.

The status of public opinion on these and other topics comprises the 12th annual Education Next (EdNext) survey of public opinion, administered in May 2018. The poll’s nationally representative sample of 4,601 adults includes an oversampling of parents, teachers, African Americans, and those who identify themselves as Hispanic. (All estimates of results are adjusted for non-response and oversampling of specific populations. See methods sidebar for further details.)

On several issues, our analysis teases out nuances in public opinion by asking variations of questions to randomly selected segments of survey participants. Respondents were divided at random into two or more segments, with each group asked a different version of the same general question. For example, we told half of the respondents—but not the other half—how much the average teacher in their state was paid before asking them whether they thought salaries should be increased, be decreased, or remain about the same. By comparing the differences in the opinions of the two groups, we are able to estimate the extent to which relevant information influences public thinking as to the desirability of a pay increase.

Some of the key findings from the poll are:

1. Teacher salaries. Among those provided with information on average teacher salaries prevailing in their state, 49% of the public say the pay should increase—a 13-percentage-point jump over the share who said so last year. Sixty-three percent of respondents in the six states that experienced teacher strikes in early 2018 favor boosting teacher pay, as compared to 47% elsewhere.

2. School spending. Among those provided information about current spending levels in their local school districts, 47% say that spending should increase, an increase of 7 percentage points over the prior year.

3. Agency fees. In June 2018, the Supreme Court reached a decision favored by majorities of the public and of teachers when it ruled that states could not allow public-employee unions to impose agency fees to cover collective-bargaining costs on workers who do not join unions. No less than 56% of the general public and 56% of public-school teachers oppose laws that require “all teachers” to “pay fees for union representation even if they choose not to join the union.” Only 25% of the public and 34% of teachers favor agency fees.

4. Union and nonunion teachers. Opinions on various issues differ widely between public-school teachers who join unions and those who do not. Nonunion members are 20 percentage points more likely to support annual testing in reading and math, charter schools, and universal school vouchers. Union members are at least 20 percentage points more likely to support increasing school spending (when informed of current spending levels), increasing teacher salaries, and giving teachers tenure; they are also more satisfied with union political activities and view collective-bargaining contracts more favorably. However, on some topics—merit pay, Common Core, school-discipline practices, and affirmative action in school assignment policies—the views of union and nonunion members do not differ significantly.

5. School vouchers. A 54% majority of the public supports “wider choice” for public-school parents by “allowing them to enroll their children in private schools instead, with government helping to pay the tuition,” a 9-percentage-point increase over a year ago. Opposition to vouchers has fallen from 37% to 31%. Approval for vouchers targeted to low-income families has not changed. Just 43% express a favorable view, the same level as in 2017. African American (56%) and Hispanic (62%) respondents are more favorably disposed toward vouchers for low-income families than are whites (35%).

6. Charter schools. After a substantial decline in support in 2017, public backing for charter schools climbed by 5 percentage points this past year, to 44%, with only 35% opposed. The uptick is concentrated almost entirely among Republicans, widening the divide between Republicans and Democrats on this issue.

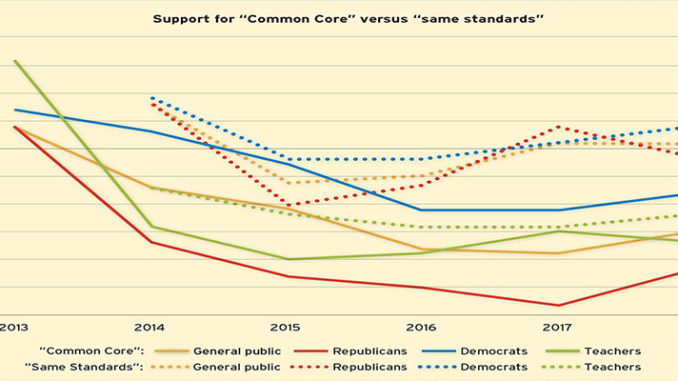

7. Common Core. After falling in previous years, opinion on the Common Core State Standards has now stabilized at 45% in support and 38% opposed. The Common Core brand remains weak, however. When half of the respondents are asked instead about using standards that are “the same across the states,” the favorable response is 16 percentage points higher than when the name Common Core is used.

8. Assessment of local schools, police, and post offices. Despite the lack of progress on NAEP math and reading tests, approximately half the public (51%) awards the public schools in their local community a grade of A or B. This percentage has remained in the low to mid-50s for the past three years, slightly higher than in earlier iterations of the EdNext survey, when the percentage was stuck in the 40s. Still, the public holds schools in lower esteem than it does the local police force or local post office, which receive a grade of A or B from 69% and 68% of the public, respectively. African Americans view both the public schools and the police force in their local communities more negatively than do other racial and ethnic groups: 39% of African Americans think the public schools in their local communities merit an A or a B, and 43% give these grades to their local police forces.

9. Racial disparities in disciplinary practices. A majority of the public seems to share the position taken by the Trump administration when it announced its intention to review—and potentially rescind—a federal-government letter to local school officials warning them that they risk incurring a civil-rights infraction if they suspend, expel, or otherwise discipline students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds at different rates. Only 27% of the public favor, while 49% oppose “federal policies that prevent schools from expelling or suspending black and Hispanic students at higher rates than other students.”

10. Affirmative action in K–12 school assignments. With the departure of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy from the Supreme Court, affirmative action in school assignment policies could re-emerge as an issue before the court in the coming years. Majorities of the public and of teachers oppose both race-based and income-based affirmative action in K–12 school assignment decisions.

11. Immigration. Only 30% of respondents favor “the federal government providing additional money to school districts based on the number of immigrant children they serve.” In locales where the proportion of foreign-born residents is above the national median, 37% of respondents endorse the proposal, but that backing drops to 22% among those living in areas with fewer immigrants.

Teacher Salaries and School Spending

In late February of this year, teachers in West Virginia walked out of their classrooms and took to the streets to protest stagnant salaries and rising health-care costs. The illegal strike, which shuttered schools across the state, lasted nine days, ending only after the legislature agreed to give the state’s teachers—among the lowest-paid in the nation—a 5% pay hike. The action was widely perceived as a successful demonstration of strength, and by May, teachers in five other states—Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Oklahoma—had conducted similar strikes or walkouts to demand better pay and, in some cases, general increases in school funding.

The timing of the 2018 EdNext Survey in the first three weeks of May affords a window on public opinion in the immediate aftermath of most of these actions. Do Americans support teachers’ appeals for better pay and increased school spending? Have they become more sympathetic to those demands in the past year? Do they believe that teachers should be permitted to go on strike in the first place? And how does opinion among residents of the six states where the walkouts occurred compare to that of other Americans?

Teacher salaries. We asked all respondents to our survey whether they thought that salaries for public-school teachers in their home state should increase, decrease, or stay about the same. As in past years, before asking this question we first told a random half of respondents what teachers in their state actually earn. Among those provided this information, 49% say that teacher salaries should increase—a 13-percentage-point jump over the share who said so last year (see Figure 1a). This hefty spike in support for boosting teacher salaries is the largest change in public opinion we observed between our 2017 and 2018 surveys.

Forty-four percent of informed respondents say teacher salaries in their state should remain about the same, while just 7% say they should decrease.

More Democrats than Republicans favor increasing teacher salaries, but support jumped in 2018 among members of both political parties. Support rose from 45% in 2017 to 59% this year among Democrats, and from 27% to 38% among Republicans. Meanwhile, teachers are even more convinced about the merits of increasing their salaries, with 76% of them registering support, up slightly from 71% in 2017.

Is this upsurge of support for better teacher pay a consequence of this spring’s labor unrest? Residents of states that experienced strikes or walkouts are more enthusiastic about raising teacher salaries than those living elsewhere. Sixty-three percent of respondents in the six states listed above favor increasing teacher pay, as compared to 47% elsewhere. This difference was also present, but was less pronounced, in 2017: 47% of respondents in states that would later experience strikes or walkouts favored boosting teacher salaries, as compared to 38% elsewhere. In other words, support for a pay hike jumped by 16 percentage points in states that experienced labor unrest, but it also rose by 9 percentage points elsewhere.

If the strikes and walkouts did in fact contribute to the changes in opinion, their impact was not confined to the states in which the actions occurred. Moreover, those six states appear to have been fertile ground for an effort to raise teacher pay, with residents more likely to support such an effort, even in 2017. These higher levels of approval could reflect the fact that each of the states ranks in the bottom 10 nationally in terms of teacher compensation.

It is also possible that the jump in support for raising teacher salaries and this spring’s labor unrest both reflect the strength of the national economy. The only year in the 12-year history of the survey in which a higher share of Americans said that teacher salaries should increase was 2008, at the peak of the housing bubble and just prior to the financial crisis that followed (see Figure 2). The fact that economic growth is finally pushing Americans’ wages upward may have emboldened teachers to demand higher pay—and made the public more receptive to that appeal.

A larger proportion of the public favors increasing teacher salaries if respondents are not first informed of what teachers currently earn. Among this segment of those surveyed, 67% say that salaries should increase, 29% say they should remain the same, and 4% say they should decrease. These numbers also reflect an upswing in support over 2017, though by a smaller amount (6 percentage points) than the surge among those informed about teacher salaries (see Figure 1b). The higher level of support for boosting teacher salaries among the “uninformed” respondents reflects the fact that most Americans believe that teachers earn far less than they actually do. When asked to estimate average teacher salaries in their state, respondents’ average guess came in at $40,181—31% less than the actual figure of $58,297.

School spending. Support for higher school spending has also strengthened in 2018, though the changes are less dramatic than those related to teacher salaries. Among those provided information about current spending levels in their local school districts, 47% say that spending should increase, a rise of 7 percentage points over the prior year. A bare majority of 53% of informed respondents would prefer that spending levels remain the same (43%) or decrease (10%). Support for spending more is also higher this year among respondents who are not first informed of current spending levels. Fifty-nine percent of these respondents support a spending hike, up from 54% in 2017. As in the case of teacher salaries, residents of states that experienced a strike or walkout are more likely to be in favor of higher spending than those elsewhere (53% vs. 46%).

Merit pay. While Americans have grown more supportive of teacher pay raises, they continue to disagree sharply with teachers over the manner in which these educators should be compensated. When asked whether part of teachers’ pay should be “based on how much their students learn,” 48% of the public express support and 36% are opposed. At 55%, approval for merit pay is higher among Republicans than among Democrats. But even Democrats are more likely to support the concept (44%) than to oppose it (41%). Among teachers, however, just 22% favor merit pay and as many as 73% are against it.

Teachers’ right to strike. As noted above, West Virginia’s teachers carried out their strike in defiance of a state law banning such actions by teachers and other public employees. Though rarely enforced, laws prohibiting teacher strikes are on the books in a majority of states, including all of those that saw walkouts this spring, except for Colorado. While state legislators may not view teacher strikes favorably, the public appears more sympathetic. A majority of 53% of respondents—whether or not they live in a state that experienced a statewide strike or walkout this year—support “public school teachers having the right to strike,” and just 32% oppose it. There is a strong partisan divide on this issue, with 67% of Democrats and just 38% of Republicans in favor. Not surprisingly, more than 7 of every 10 teachers support the right to strike; just 2 of 10 oppose it.

Teachers and Teachers Unions While teacher strikes and controversies over school spending captured the headlines this past school year, no less important for teachers, and particularly for teachers union leaders, was the June decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that found agency fees unconstitutional. What do the general public and teachers themselves think about agency fees, the collective-bargaining process, and the influence of teachers unions? And how do the views of public-school teachers who are members of unions on these and other education policy topics compare to those who have chosen not to join their union?

Agency fees. A month after we fielded our survey, the Supreme Court ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that government employees couldn’t be required to pay an agency fee in lieu of dues if they do not join the union representing them in collective bargaining. The court decided, by a 5–4 vote, that these fees unconstitutionally compel employees to pay for the costs of speech with which they disagree. Teachers union leaders say agency fees are needed to cover the cost of collective bargaining and without them employees are tempted to “free ride” on the contributions of others. Eric Heins, president of the California Teachers Association, insists that “corporate CEOs, the wealthiest one percent, and politicians who do their bidding” launched the lawsuit. “They want to use the Supreme Court to take away the freedom of working people to join together in strong unions,” he says.

As it turns out, the Supreme Court decision has the approval of a larger share of both teachers and the general public than just the “wealthiest one percent.” No less than 56% of the public and 56% of public-school teachers express opposition to laws that require “all teachers” to “pay fees for union representation even if they choose not to join the union” (see Figure 3). Only 25% of the public and 34% of teachers favor agency fees. The remaining respondents say they neither support nor oppose them.

Public disapproval is greatest among those living in right-to-work states (61% against, 20% in favor), which already have laws that ban agency fees. But even in states that currently permit agency fees, a majority disapproves of the practice (51% to 31%).

Support for fees is higher among those given arguments in favor and against them. Before we asked a random half of our respondents for their opinion, we told them the following: “Some say that all teachers should have to contribute to the union because they all get the pay and benefits the union negotiates with the school board. Others say teachers should have the freedom to choose whether or not to pay the union.”

When given both sides of the argument, 52% of public-school teachers remain opposed, while 39% favor agency fees. Among the general public, support for agency fees shifts upward to 37%, but the negative view, at 44%, still commands a plurality. Partisan differences are large: 56% of Republicans, but only 35% of Democrats, oppose agency fees after hearing the arguments for and against the practice.

Although a plurality of the public is not any more inclined than a majority of the Supreme Court to allow agency fees, that opposition does not necessarily translate into a negative view of teachers unions. When those surveyed are asked whether they think the effects of unions are “generally positive” or “generally negative,” responses divide almost evenly (35% pro, 36% con), with 29% saying they had neither a positive nor a negative impact. Again, the division of opinion falls sharply along partisan lines, with 55% of Republicans, but just 22% of Democrats, saying unions have a negative effect. Public-school teachers, meanwhile, think that unions have a positive impact by an overwhelming 57% to 25% margin.

Respondents split almost down the middle when asked to weigh in on collective-bargaining contracts. When directed to choose between two statements, 54% say their view comes closer to the assertion that such contracts “produce so many rules and restrictions that they make it difficult for schools to perform well,” while 46% think a contract “produces reasonable rules and regulations that help schools perform well.” Sixty-five percent of Republicans pick the first statement, while 58% of Democrats select the second. The division among teachers is 60% to 40% in favor of the more-positive characterization.

But if the public divides over collective bargaining, a more unified view emerges on the topic of teacher tenure. Respondents oppose the practice by a clear plurality (33% in support to 48% against), while teachers, as might be expected, are overwhelmingly in favor of tenure—62% to 24%.

Union and nonunion public-school teachers. The Janus decision says agency fees deny nonunion members their freedom of speech by compelling them to support views different from their own. But do union and nonunion employees truly differ in their opinions? Or are the non-members simply free riders who enjoy the benefits of collective bargaining while not paying the costs?

To find out, we asked our oversample of teachers whether they were union members and whether they taught in public, private, or charter schools. That question gave us a sample of 228 public- and charter-school teachers who self-identify as union members, 195 public- and charter-school teachers who say they are not union members, and 86 private-school teachers, whom we omit from this analysis.

The degree to which union and nonunion public-school teachers differ in their opinions depends on the issue in question (see Figure 4). We detect little or no difference in opinion when it comes to merit pay, Common Core, discipline practices, and affirmative action in school assignments. But on other issues more directly related to union concerns, differences are large. For example, when asked about agency fees and given the arguments on both sides, only 16% of the nonunion teachers say they are in favor of the fees, compared to 65% of union teachers. When given the arguments on both sides before being asked whether unions have a positive or negative impact on schools, differences loom almost as large: 77% of union teachers and 56% of nonunion teachers say they have a positive impact. Other issues that generate at least a 20-percentage-point difference of opinion include: 1) the reasonableness or restrictiveness of collective-bargaining contracts; 2) universal vouchers; 3) federal requirements for annual testing in reading and math; 4) charter schools; 5) union influence on school quality; 6) teacher tenure; 7) school-spending levels; 8) teacher salary levels; 9) teacher tenure; and 10) satisfaction with union political activities. Clearly, the free-speech issues surrounding the agency-fee decision go well beyond plaintiff Mark Janus. Union leaders may find themselves seriously challenged as they seek to sustain union membership in the post-Janus political environment.

School Choice

School choice has received unprecedented media attention since the inauguration of Donald J. Trump in January 2017. His appointment of an avowed choice advocate, Betsy DeVos, as secretary of education, has mobilized both enthusiasts and detractors. At her 2017 confirmation hearing, she expressed unqualified backing for multiple forms of parental choice:

It’s time to shift the debate from what the system thinks is best for kids to what moms and dads want, expect and deserve. Parents no longer believe that a one-size-fits-all model of learning meets the needs of every child, and they know other options exist, whether magnet, virtual, charter, home, religious, or any combination thereof. Yet, too many parents are denied access to the full range of options . . . choices that many of us—here in this room—have exercised for our own children.

If DeVos has warmed the hearts of many in the choice community, she has provoked unreserved opposition from teachers unions, allied advocacy groups, and Democratic senators, who voted unanimously against her confirmation. When two Republican senators decided to join them, it fell to the vice president to cast the deciding vote in DeVos’s favor.

For DeVos, school choice should be, for the most part, the product of state and local decisions, not “a new federal mandate from Washington,” as she put it in a fall 2017 speech at the Harvard Kennedy School. Still, the U.S. Department of Education under DeVos has proposed expanded federal funding for charter school start-ups, a redesign of the compensatory education program that would foster parental choice, and a new choice program for military personnel.

To find out if public thinking on school choice has shifted in the midst of this federal advocacy, we asked, in addition to new queries, the same questions about vouchers, charters, and tax-credit scholarships we posed in prior years.

Vouchers. According to EdChoice, a pro-voucher interest group, 15 states have enacted 26 different voucher programs. Still, the organization’s own numbers concede that fewer than 200,000 students make use of vouchers, a minuscule share of the nearly 50 million students attending public schools in 2018. But do these voucher programs have a greater potential to grow in the Trump-DeVos era than in the past? Four poll questions—two old and two new—inquired about support or opposition to school vouchers. Each question was administered to a separate, randomly selected segment of our overall sample of respondents, enabling us to detect the responsiveness of opinion to specific wordings of the question. The two old questions ask respondents whether they favor “greater choice” for families by having the government help pay the tuition to attend a private school. To see how the public responds, specifically, to the word “voucher,” the two new questions substitute that term for the phrase “greater choice.” The following contains the wording for all four versions of the voucher question, with the differences among the versions indicated by deletions (in italics) and substitutions (in brackets):

A proposal has been made that would give all [low-income] families with children in public schools a wider choice, by [vouchers] allowing them to enroll their children in private schools instead, with government helping to pay the tuition. Would you support or oppose this proposal?

As mentioned, the two versions that do not include the word “vouchers” are identical to the question we asked in 2017, allowing us to estimate any changes in opinion over the past year. When respondents were asked about “all” families (universal choice), approval rose by 9 percentage points between 2017 and 2018 (see Figure 5). A year ago, only 45% of respondents said they favored universal choice, but that percentage jumped to an overall majority of 54% in 2018. Disapproval fell from 37% to 31%. The remaining respondents said they neither supported nor opposed the policy. The increase in support occurred among both Republicans and Democrats. Backing among Republicans for universal vouchers has bumped upward by 10 percentage points, to 64%, while among Democrats the rise has been 7 percentage points, to 47%. No significant differences among whites, blacks, or Hispanics are observed.

Opinion holds steady, however, when respondents are asked about “wider choice” for “low-income” families. Just 43% express a favorable view, the same as in 2017. African Americans (56%) and Hispanic (62%) respondents are considerably more supportive of vouchers for low-income families than are whites (35%).

Sponsors of choice programs enacted by both Congress and state legislatures typically use the word “scholarship” rather than “voucher,” believing that the term “voucher” has become toxic from criticism of the concept over many years. To assess this belief, we substituted “vouchers” for the phrase “wider choice” in the question above. As it turns out, the toxicity of the v-word, as vouchers are sometimes termed, depends on context. No significant change in opinion is detected when it is inserted into the question that refers to “low-income” families. But approval of the universal vouchers falls by 10 percentage points when “voucher” is substituted for the “wider choice” phrase.

Charters. Although charter schools are authorized by state entities and receive most of their funding from the government, they differ from other public schools in that they are privately managed under the direction of a nonprofit board. According to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, over 3.2 million students, roughly 7 percent of the U.S. public-school population, attend one of the 7,000 charter schools in the 44 states that have authorized them. Parents must choose to send their child to a charter school, and, generally speaking, the school must accept all qualified applicants unless it is oversubscribed, in which case an admissions lottery is held. As charter enrollment has grown, school-district and teachers-union opposition to the formation of new charter schools has intensified.

This opposition has apparently had an effect on public opinion: in 2017 we reported a hefty 13-percentage-point drop in support for the formation of charter schools. However, a partial recovery of 5 percentage points has occurred over the course of the past year, allowing charters to regain a plurality approval rate of 44% in the halls of public opinion, with just 35% of the general public opposed. (Remaining respondents say they neither support nor oppose charters.) Among teachers, however, support for charter schools has fallen from 40% to 33%. White respondents (42%) are nearly as supportive as black (46%) and Hispanic (49%) ones, but the charter recovery is concentrated among Republicans; approval for charters among GOP voters has climbed from 47% to 57%. As a result, the charter debate has become increasingly polarized across party lines, with only 36% of Democrats now supporting their formation.

“Charter” is nonetheless a benign word. When we drop the term from the description of these schools, approval for charters falls by 6 percentage points, with most of the decrease concentrated among Republicans, for whom it is 10 percentage points. But inserting the word “public” to produce the awkward phrase “public charter schools” does nothing to help the cause of public-charter-school advocates.

Tax-credit scholarships. Eighteen states have enacted tax-credit scholarship programs. Depending on the state’s authorizing language, these programs allow either individuals, corporations, or both to donate money to a foundation that provides scholarships to children from low-income families and receive a tax credit for most, if not all, of their contribution. Private schools tend to favor these programs, because they generally entail only limited state regulation of the schools. The programs also appeal to taxpayers, because the amount of money the state gives up in tax receipts is often less than the cost of educating a child in a public school. This form of school choice is so popular that proponents succeeded in persuading the legislature of deep-blue Illinois to enact a tax-credit program.

The public at large also endorses the concept. In 2018, we again find a clear majority—57%—in favor of “a tax credit for individual and corporate donations that pay for scholarships to help low-income parents send their children to private schools.”

In sum, school choice did not lose ground and may well have gained political favor over the past year. Despite heavy criticism of choice-advocate DeVos by union officials and Democratic politicians, support for universal school vouchers and charter schools is higher than it was in 2017, and targeted vouchers and tax credits have held their own in the court of public opinion. The gains have been concentrated among Republicans, to be sure, but they have occurred without offsetting losses among Democrats. Of course, we cannot say whether these gains are attributable to DeVos’s unqualified endorsement of choice or to some other factor, but choice in 2018 has certainly enjoyed a boost in public favor.

Common Core, Testing, and Accountability

The Common Core State Standards initiative began in 2009 as an effort by states to develop more uniform content standards and testing policies aimed at preparing students for college and career experiences. Most states adopted the standards with little fanfare by 2011, after the Obama administration provided incentives through its Race to the Top initiative. Common Core soon became a national political flash point, however, when Tea Party organizations and other conservative groups mobilized intense opposition to the standards. At the same time, the teachers unions, which had initially favored the standards, came to worry that student performance on tests keyed to the standards would be used to evaluate teacher performance, and they too began to criticize the implementation of Common Core. When the standards became a matter of national contention in 2014, public support eroded further.

While debate over Common Core has largely faded, the standards themselves have not. Most states have quietly raised their standards to levels roughly equivalent to those originally envisioned in the Common Core initiative, though in most cases the standards no longer wear the “Common Core” label. As political and media attention has drifted to other issues, erosion in public approval for national standards has come to a halt, and opinion may be turning around. Support for Common Core now stands at 45%, compared to 41% a year ago, and the level of disapproval remains unchanged, at 38% (see Figure 6). Among teachers, however, support for Common Core slipped by 2 percentage points over the past year to 43%, an insignificant change, and opposition rose seven points to 51%.

GOP opposition remains stauncher than that of Democrats. In 2012, the parties showed no discernible difference in this regard, but favor among Republicans dropped more precipitously (and earlier) than among Democrats, opening a double-digit partisan gap just two years later. Opinion within each party largely crystallized by 2016, leaving Republicans and Democrats divided on the issue. Roughly half of Democrats (52%) favor the Common Core standards, with 30% opposed, while only 38% of Republicans support the standards and 50% oppose them.

The name Common Core remains toxic. When we ask a randomly selected subset of respondents about common standards across states without invoking the name Common Core, 61% of Americans support the policy—a 16-point jump over positive responses to the same question using the brand name. The effect of the name is only modestly larger among Republicans (-20 points) than among Democrats (-12 points). Among Republicans, this change has the effect of shifting the balance of opinion from opposition to support. Whereas half of Republicans oppose Common Core, 58% endorse the idea of common standards shared across states when the name is dropped.

In another sign that the accountability debate has been winding down, a large majority of Americans continue to support the federal requirement that all students be tested in math and reading each year in grades 3 through 8 and once in high school. Approximately two-thirds (68%) of Americans support this mandate, and this level of approval has held steady over the past several years. Favor is similarly high across most demographic and political characteristics examined in the survey, with the exception of teachers. Teachers split almost evenly over the federal testing requirement, with 48% in favor and 51% against. Like opinion among the overall population, teacher views on the mandate have been stable over the past four years.

When asked to rate the schools in their local community, approximately half of Americans (51%) assign them a grade of A or B. This percentage has remained in the same range for the past three years, slightly higher than in earlier EdNext polls, when it was mired in the 40s. Evaluations of local public schools are somewhat higher among parents of school-age children, 57% of whom give them an A or a B, and significantly higher among teachers, 67% of whom do so.

As in previous years, Americans are much less sanguine about the public schools in the nation as a whole. Just 24% of Americans give the country’s public schools a grade of A or B. Similarly, most believe elementary and secondary schools in the United States are not as good as those in similarly developed countries. Overall, 53% say schools here are worse, and only 24% hold that they are better. Even among teachers, who generally think more highly of schools than the general public does, 49% say American schools are worse than those in similarly developed countries and mirroring the general population, just 24% say they are better.

Local schools compared to other community services. That Americans give higher grades to their local public schools than to those nationwide is often taken as a sign that people are satisfied with the schools they know best. But that is a strong conclusion to reach when only a little more than half of Americans assign their local schools an A or a B, despite the strong psychological pressure to view one’s own circumstances favorably. To get an alternative comparison for opinion on local schools, we asked respondents to grade the performance of other public-sector services in their communities, specifically the postal service and law enforcement. Both receive higher ratings than local public schools: 68% of Americans grade their local post offices with an A or a B, and 69% give those top marks to their local police forces (see Figure 7). In other words, even though Americans think their local public schools outperform public schools in the nation as a whole, they also think they underperform other important local services. Even teachers, who have the most positive views of public schools, rate the other two government services more highly: 76% give their local post offices an A or a B, and 80% do so for their local police forces.

Republicans and Democrats hold their local post offices in equally high regard, much as they agree about their local public schools. There are differences, however, when it comes to views of local police. For example, more Republicans (77%) than Democrats (64%) give local law enforcement an A or B grade, although members of both parties view police more positively than they do public schools.

A larger rift in opinion emerges along racial lines. African Americans view both the public schools and the police forces (but not the post offices) in their local communities more negatively than do other racial and ethnic groups. Only 39% of African Americans think the public schools in their local communities merit an A or a B, while 56% of Hispanics and 52% of non-Hispanic whites do so. A similar share of African Americans (43%) gives these grades to local police forces, but 60% of Hispanics and 76% of whites give the police an A or a B.

Even though African Americans, on average, hold the quality of police and school services in similarly low regard, the trajectories in these views over time differ. The share of African Americans giving their local police forces an A or a B fell 12 percentage points, from 55% in 2008, when Education Next last asked this question, even as the share of whites giving these grades to their local police rose by 9 percentage points. Meanwhile, over the past decade, the share of African Americans saying their local public schools deserve an A or a B has climbed by 15 points—outpacing the 8-point improvement in opinion among whites. As a result, African Americans and whites have moved closer together in their estimations of their local schools, with the gap between the two groups shrinking from 20 to 13 percentage points. At the same time, the difference in their views of local police forces has grown from 12 to 33 percentage points.

The racial difference also extends to how people evaluate the effect of police unions on the quality of policing. Among African Americans, 24% say these unions have a positive effect and 41% say they have a negative effect. Among whites, 35% say positive and 31% say negative. But this pattern reverses when it comes to teachers unions: African Americans tend to hold a more favorable view and whites lean toward a more critical one. Nearly half of African American respondents (48%) say teachers unions have a positive effect on schools and 19% say they have a negative effect. Among whites, 32% say positive and 41% say negative.

As mentioned above, the public as a whole is equally split in its views of teachers unions’ influence: 35% say they have a positive effect on schools, 36% say a negative effect, and 29% say they have neither a positive nor a negative effect. Opinion is similarly divided about the effect of police unions on the quality of policing (34% positive and 32% negative) and slightly more favorable on the effect of postal workers’ unions on the quality of the postal service (38% positive and 28% negative). Democrats are more likely to believe that unions have a positive effect on the quality of services, but the partisan gap is smaller for police unions (38% of Democrats and 31% of Republicans) than for postal workers’ unions (48% of Democrats and 26% of Republicans) and teachers unions (48% of Democrats and 20% of Republicans). In other words, Democrats hold lower opinions of police unions than of other public-sector unions, while Republicans think more highly of police unions than of other public-sector unions.

Teacher quality. Despite Americans’ divided views on teachers unions, they hold teachers themselves in high regard. On average, the general public says 25% of teachers in their local schools are excellent, 31% are good, 28% are satisfactory, and only 16% are unsatisfactory. Parents and teachers are slightly more positive in their evaluations. Parents of school-age children say that 61% of teachers in their local schools are excellent or good, while 67% of teachers give their colleagues those rankings. Parents hand out the unsatisfactory rating to just 15% of teachers, not much higher than the 12% of colleagues that teachers deem below what is acceptable.

Home vs. school. Finally, we asked respondents which is more important for a child’s academic learning—the home or the school. Americans are split, but lean moderately toward believing the home matters more: 39% point to the home while 31% give the nod to the school (another 31% say they are of equal importance). The views of parents of school-age children are similar: 37% say the home and 29% say the school. Teachers, meanwhile, are much more likely to say the home is more important for academic learning than the school. Nearly half of teachers (47%) choose the home and just 18% opt for the school.

This divergence between parents and teachers is striking. Perhaps teachers observe stark contrasts among the home backgrounds of their students and conclude that the home has the greater impact, while parents see dramatic differences in the quality and effectiveness of their children’s teachers and conclude that school quality is what counts.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities: School Discipline and Affirmative Action

Racial and ethnic issues continue to figure prominently on the national education agenda. At the University of Virginia, civil-rights and “white supremacist” groups have clashed over the presence of Confederate statues on campus, and the Trump administration has announced its intention to review guidance concerning racial disparities in school discipline promulgated by the Obama administration. The retirement of Supreme Court justice Kennedy, who cast deciding votes on numerous cases addressing affirmative action in college admissions and K–12 school assignment policies, may open the door to further litigation on this issue before the high court.

Racial disparities in school-discipline practices. In 2014, the Obama administration’s departments of Education and Justice, acting jointly, sent a “Dear Colleague” letter to school superintendents nationwide warning that their district would risk incurring a civil-rights violation if its schools suspended, expelled, or otherwise disciplined students of color at higher rates than they punished others. Though they account for only 15 percent of public-school students, the letter notes, black students comprise 36 percent of all reported expulsions. Conservatives allege that the letter intrudes on prerogatives that properly belong to state and local governments, and the U.S. Department of Education has announced its intention to review the policy, a step that has drawn heavy criticism from civil-rights groups.

In 2015, a year after the “Dear Colleague” letter was sent, we asked respondents whether they supported or opposed “federal policies that prevent schools from expelling or suspending black and Hispanic students at higher rates than other students.” Only 21% of the public favored the policy, while 51% disapproved of it, and the remainder took neither position. Teachers were also overwhelmingly opposed (59% to 23%).

Now, shortly after the Trump administration’s announced review of the letter, we have asked this question again. Support for federal limits on racial disparities in student-discipline practices remains at a low 27%, though this constitutes an uptick of 6 percentage points, all of which is concentrated among Democratic respondents, whose level of approval has shifted upward from 29% to 40% (see Figure 8). We find no significant change in the views expressed by Hispanics. Although endorsement of these federal policies also remains unchanged among African Americans, disapproval has increased 12 percentage points, from 23% to 35%.

Conservatives allege that the “Dear Colleague” letter is misguided because it imposes an unwarranted federal mandate on state and local education authorities. Do the principles of American federalism also affect public thinking on this issue? To find out, we divided our sample into two segments, asking one the policy question just quoted above while asking the other group the same question but substituting the phrase “school district” for “federal.” Responses to the two variants of this question do not differ significantly from one another, except that Democrats, curiously enough, are 5 percentage points less likely to favor rules against racial disparities set at the district level than at the federal level, a marginally significant difference. Support for these policies at the district level also climbed 11 percentage points among Hispanic adults, from 25% in 2015 to 36% this year. Meanwhile, opposition to such district policies increased to 67% among Republicans—an 8-percentage-point rise since 2015.

In sum, the public takes essentially the same position with respect to school-discipline disparities regardless of the level of government that designs the policy, and the only significant change in public opinion since 2015 has been a further polarization along partisan lines. Opinions vary by ethnic background, with African Americans increasingly opposed to these policies set at the federal level and Hispanics increasingly in favor of these policies set at the district level.

Race- and income-based school assignments. In 2007, the admissions policies of the Board of Directors for Seattle Public Schools gave priority to students who enhanced the racial diversity of a school when the institution had more applicants than it could admit. That summer, the Supreme Court found the practice unconstitutional by a 5–4 vote, averring that it classified “every student on the basis of race” in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. To gauge public opinion on the court’s decision, in 2008 we asked whether the respondent thought “public school districts,” in order to “promote school diversity,” should “be allowed to take the racial background of students into account when assigning students to schools.” At that time, 63% said definitely or probably not, while only 16% said definitely or probably yes. Another 21% said they were “not sure.” Among public-school teachers, these percentages were 61%, 19%, and 20%, respectively.

The federal government’s guidance to school districts on the implications of the court’s 2007 decision has shifted across presidential administrations. Under George W. Bush, the Department of Education wrote that the decision effectively barred the use of race in school assignments and encouraged districts to employ race-neutral strategies when seeking to promote school diversity. The Obama administration, in 2011, adopted a more liberal interpretation suggesting that the use of race is still permissible in some situations, such as when race-neutral approaches prove ineffective in achieving school diversity. This June, Secretary DeVos rescinded that document and restored the more cautious guidance promulgated under president Bush.

To discern whether public opinion on this topic has shifted over the past decade, we asked the same question this year that we posed in 2008. We find that the public remains overwhelmingly opposed to considering race when assigning students to schools, though the margin of difference has narrowed a bit (see Figure 9). Among the general public, support has edged up by an insignificant 2 percentage points, to 18%, but opposition has fallen by 6 percentage points, to 57%. Among public-school teachers, the share responding in favor is now 27%, representing an 8-percentage-point increment. Among African American adults, the tick upward is a negligible 1%, but opposition has declined to 46%, a 12-percentage-point drop. Among Hispanic adults, the share taking a favorable position has increased by 10 percentage points, though a majority of this group remains opposed (51% to 24%). Only 11% of Republicans and 25% of Democrats favor race-based school assignment. In other words, a solid majority of the public remains opposed to race-based school assignment policies even when aimed at increasing school diversity.

In light of that opposition as well as uncertainty about the direction of future court decisions, liberal policy analysts have suggested income-based affirmative action as an alternative. “Class-based admissions and recruitment strategies can be effective tools for guaranteeing both racial and socioeconomic diversity on campus,” argues Richard Kahlenberg of the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank. Bill de Blasio, the mayor of New York City, has urged wider access to the city’s selective high schools for students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and the Supreme Court seems to have found no constitutional objection to income-based admissions policies.

To assess the public’s view of this approach, we divided our sample into two segments, asking one the 2008 question about race-based school assignments, while asking the other the same question but substituting for “racial background” the words “family income.” The responses reveal little difference in levels of support for income-based and race-based affirmation action. If anything, approval of income-based affirmative action is even lower. The biggest difference is for African Americans, who are 13 percentage points less supportive of the income-based alternative.

With the 2016 presidential election campaign, immigration policy came to the fore of our national consciousness. Trump’s promises to build a wall and tighten the availability of foreign visas have sparked impassioned debate. A few weeks after the administration of the 2018 EdNext survey, fury over immigration policy boiled over with the administration’s decision to prosecute all adults entering the United States illegally, resulting in the separation of children from their families.

Federal aid for immigrant schoolchildren. With U.S. primary and secondary schools daily facing the task of serving 2.3 million foreign-born children—about 4 percent of total enrollment—the immigration issue naturally spills into common discourse about our educational institutions. States and localities with large numbers of immigrant schoolchildren have repeatedly sought federal aid to cover the cost of what is a national challenge, not just the concern of the specific state in which migrants settle. As it turns out, the public is not particularly friendly toward helping out those most affected by migration (see Figure 10). Only 30% of respondents favor “the federal government providing additional money to school districts based on the number of immigrant children they serve.” Almost half of respondents are opposed, with the remainder undecided.

As one might expect, support for the proposal was higher in geographic areas with greater concentrations of immigrants. In locales where the proportion of foreign-born residents is above the 9.3% national median, 37% of respondents endorse the proposal. Backing for the policy drops to 22% among those living in areas with fewer immigrants.

Nationwide, some segments of the public are more likely to approve additional federal aid for immigrants. Forty-three percent of Democrats favor the idea, and opinions among teachers are similar. Approval is highest among Hispanics, at nearly 50%, and lowest among Republicans, with only 14% in favor and 71% against.

Does the public become more willing to support federal aid for immigrant students if they are told the percentage of residents in their district who are foreign-born? We conducted an experiment to answer this question. Before soliciting their opinion about additional federal aid, we told a random half of our respondents the proportion of foreign-born individuals living in their local area. Among those so informed, 36% support the proposal—a 6-percentage-point increase from 30% in favor among respondents not given the information. The positive shift in backing for federal aid for immigrants is fairly uniform across all segments of the population.

Visas for specialized workers. To further assess the public’s attitudes toward immigrants and immigration, we asked respondents to say whether the U.S. government should increase or decrease the number of visas for highly educated foreign workers. As we did in the 2017 EdNext poll, we informed respondents that 85,000 visas were currently provided and offered them arguments on both sides of the issue: some people say these visas are necessary for filling vital jobs, while others say they take jobs away from American college graduates.

Only 17 percent of the public supports increasing the number of visas, representing just an insignificant change from the 15 percent who held that view last year. Forty-six percent of respondents prefer to keep the number of visas at its current level. The remaining 37% favor decreasing the number. The political ramifications of the Trump administration’s new regulations of the H1-B visa program will likely become clearer after their actual effect on the number of foreign workers in the United States unfolds.

Albert Cheng is assistant professor in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas College of Education and Health Professions. Michael B. Henderson is assistant professor at Louisiana State University’s Manship School of Mass Communication and director of its Public Policy Research Lab. Paul E. Peterson, professor of government at Harvard University, directs its Program on Education Policy and Governance (PEPG) and is senior editor of Education Next. Martin R. West, professor of education at Harvard University, is deputy director of PEPG and editor-in-chief of Education Next.

Download the full results of the 2018 Education Next survey here.

| Methodology

This is the 12th annual Education Next survey in a series that began in 2007. Results from all prior surveys are available at educationnext.org/edfacts. The results presented here are based upon a nationally representative, stratified sample of 4,601 adults (age 18 and older) and representative oversamples of the following subgroups: parents with school-age children living in their home (2,129), teachers (641), African Americans (624), and Hispanics (799). Respondents could elect to complete the survey in English or Spanish; 293 respondents elected to take the survey in Spanish. Survey weights were employed to account for non-response and the oversampling of specific groups. The survey was conducted from May 1 to May 22, 2018, by the polling firm Knowledge Networks (KN), a GfK company. KN maintains a nationally representative panel of adults (obtained via address-based sampling techniques) who agree to participate in a limited number of online surveys. We report separately on the opinions of the public, teachers, parents, African Americans, Hispanics, white respondents with household incomes below $75,000, white respondents with household incomes of $75,000 or more, white respondents without a four-year college degree, white respondents with a four-year college degree, and self-identified Democrats and Republicans. We define Democrats and Republicans to include respondents who say that they “lean” toward one party or the other. In the 2018 EdNext survey sample, 53% of respondents identify as Democrats and 42% as Republicans; the remaining 5% identify as independent, undecided, or affiliated with another party. In general, survey responses based on larger numbers of observations are more precise, that is, less prone to sampling variance than those made across groups with fewer numbers of observations. As a consequence, answers attributed to the national population are more precisely estimated than are those attributed to groups (teachers, African Americans, and Hispanics). The margin of error for binary responses given by the full sample in the EdNext survey is roughly 1.4 percentage points for questions on which opinion is evenly split. The specific number of respondents varies from question to question, owing to item non-response and to the fact that, for several survey questions, we randomly divided the sample into multiple groups in order to examine the effect of variations in the way questions were posed. The exact wording of each question is available at educationnext.org/edfacts. Percentages reported in the figures and online tables do not always sum to 100, as a result of rounding to the nearest percentage point. |