by Romy Drucker

One of my goals this year is inspiring fellow millennials to join the work of improving America’s public schools.

Last November, I wrote in The 74 about the results of a poll showing that millennials believe education provides the best opportunity for success in life — much more so than factors like how much money you have or who your connections are. As with baby boomers and Generation X, the value millennials put on getting a good education seems imprinted in our DNA.

It’s not a stretch to say our generation will bend the arc of education in America; that’s an inevitability. Unless post-millennials embodied by the Parkland teen movement, which has made change in weeks that once took decades, get there first.

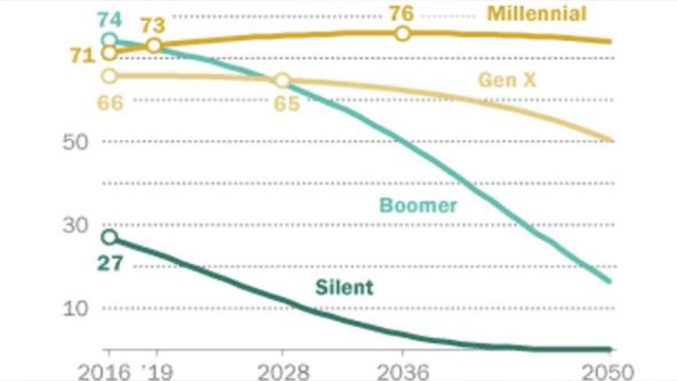

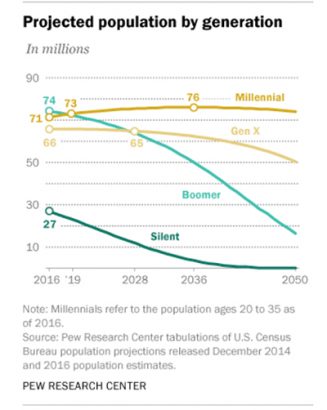

Depending on how you draw the boundaries for what defines my generation — the Pew Research Center recently argued persuasively that the brackets should be 1981-1996 — we’re about 75 million strong, almost one-quarter of the population and soon to be, if not already, the largest generation in American history. The Brookings Institution estimates we’ll comprise 75 percent of the workforce by 2025.

Another reason we’ll have a huge impact on education: We have a lot of it. More millennials have completed college than did Gen Xers or baby boomers, according to Pew, and education is associated with social participation, influence, and social capital. (And we’re still graduating.)

Another reason we’ll have a huge impact on education: We have a lot of it. More millennials have completed college than did Gen Xers or baby boomers, according to Pew, and education is associated with social participation, influence, and social capital. (And we’re still graduating.)

What’s more, nearly twice the percentage of millennial women have earned higher ed degrees as boomer-era women did — 27 percent to 14 percent, with Gen X women at 20 percent. (Only 9 percent of our grandmothers, the so-called “silent” generation, earned degrees.) It’s also worth noting that 36 percent of millennial women earned a bachelor’s degree or more, compared with 29 percent of millennial men.

These differences speak dramatically to the growing numbers of women in the workforce and in top management positions, as well as the need to provide equal opportunities to all those who have been historically underserved. That’s the overarching mission of 21st century education.

Millennials bring larger numbers, along with skills hard and soft and much richer diversity in thinking about problems than any previous generation.

And yet. The education industrial complex has resisted changes for more than a century. And billions of dollars spent to reduce race and income disparities since the 1960s have still left poor and minority children years behind — a gap that today is widening between more and less affluent students.

Change is never easy, but millennials are still a good bet to improve schools. Here’s why:

We owe less to the educational status quo. This is the necessary but not sufficient pretext for innovation. A GenForward poll from last fall found that about 75 percent of millennials across ethnic groups believe poor students get a worse education than affluent ones, and most think schools “are not held accountable for the performance of children of color.”

Respondents backed traditional solutions like more funding and improved teacher training and pay, but most — a higher percentage than other Americans — also endorsed breaking from zip-code-based enrollment systems by exercising choice through public charters and private school vouchers (particularly on a merit basis).

We’re diverse. Millennials are much more likely to be part of an ethnic group than past generations, Pew reports. Just 56 percent of the millennial generation is white, compared with 79 percent of our grandparents.

In ways that most older arrivals no longer face as keenly, the fight against discrimination and the hope for fair treatment runs deep for many millennials.

We live in cities. Sixty-eight percent of baby boomers lived in metropolitan areas; today, 88 percent of millennials do. But here’s the twist: Millennials have “cultural and educational markers of privilege” but aren’t also economically privileged (yet) and can’t afford to live in tonier areas with the best schools, as Conor Williams has observed in The 74.

The result — and it’s already evident in parts of Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. — is that culturally privileged millennials will demand better local schools in their neighborhoods and better access to good schools elsewhere in their cities. They will build political will for open enrollment systems, expanded school choice, and integration.

Plus, as Williams points out, in many millennial households, both parents need to work, which means quality pre-K will soon become an essential feature of urban systems. So parenthood could make reformers of us all.

We believe jobs should reflect our values. We care more about working for, buying from, and investing in companies that do good. The Brookings Institution cites a study in which nearly two-thirds of millennials expected employers “to contribute to social and ethical causes they felt were important” — a value shared by only half of boomers and Gen Y.

Call it entitled (many do), but millennials demand that those who employ us — including school districts — “refocus their vision and recognition programs on their employee’s efforts to ‘change the world,’” Brookings says. Those that don’t “risk losing … their economic relevance.”

To date, these social responsibility efforts have largely centered on environmentalism and civil rights, but there’s no reason that industry can’t also be leveraged by workers passionate about education. (In fairness, some companies already support education initiatives.)

We’re action-oriented. Public opinion ping-pongs between clichés of millennials as knee-jerk idealists or narcissists too busy curating our Instagram profiles. Inasmuch as a group as big as we are can share one quality, it’s that we’re radical pragmatists. We value results over ideology, distrust instructions handed down by established authority, believe there’s a fix for every problem. And we’re gifted with antennas tuned to social injustice. In a study by the Millennial Impact Project, 3,000 millennials reported engaging in “13,000 actions related to causes and social issues they cared about from July 2016 to July 2017, or more than 1,000 per month.”

Millennial babies didn’t grow up to sit on advisory committees. We’re born change agents.

But when it comes to education, we need a narrative. Education is local, but it needs a national argument. Political candidates who only give it lip service during campaigns are shortchanging voters and missing a huge opportunity.

Education doesn’t simply provide the knowledge and skills children need as adults. It’s also a critical health care issue (finishing high school has the same benefit as quitting smoking, for instance), a criminal justice issue (a five-point rise in graduation would save $18 billion in annual crime-related costs), and an economic issue: A 2014 study found that closing the racial learning gap would enlarge the economy by 6 percent; the GDP would grow on average by more than half a trillion dollars annually in coming years.

Education is at the core of the American dream. As more millennials get that, watch us rise together.

Romy Drucker is the co-founder and CEO of The 74.

email: [email protected] or @romydrucker