by Charles Blahous

The 2018 Social Security and Medicare trustees’ reports have been released. For the first time in several years they contain some big (in addition to their usual bad) news: the combined Social Security trust funds and the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund will begin drawing down their reserves this year, on their respective ways to eventual depletion. In the case of Medicare HI, that depletion is now projected to occur in just eight short years, by 2026.

The key finding, however, is not what happens in 2026 but now. Since 2010 Social Security has been coping with its annual cash deficits –the amount by which its tax income falls short of benefit obligations – by drawing upon interest earned on its nearly $2.9 trillion dollars in trust fund reserves. Those interest credits are paid from the federal government’s general fund and until now have been sufficient to allow the nominal balance of Social Security’s combined trust funds to grow. This year that will stop.

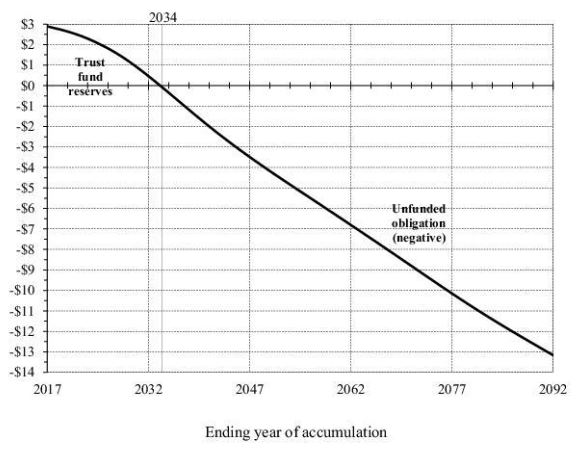

The trustees have determined that beginning this year, Social Security’s tax income and interest earnings will no longer be sufficient to finance payments. To continue making benefit payments in full, Social Security will start drawing down its trust fund reserves. The trustees further project that this drawdown will continue every year until the reserves are wholly depleted. See Figure 1, reproduced directly from the trustees’ reports.

Figure 1: Projected Drawdown of Social Security Reserve Balances

(Figure II.D5 from the 2018 Social Security Trustees Report)

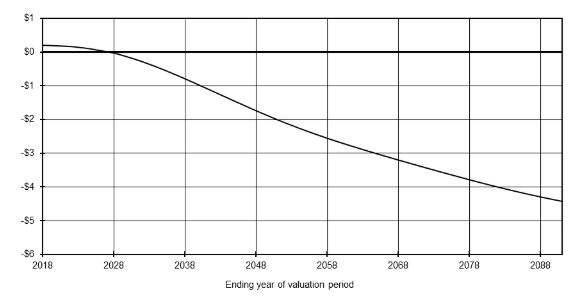

Medicare HI, the trustees find, is in the same boat. Medicare has two trust funds: the HI trust fund and the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund. SMI operates differently in that under law it can never be depleted. It is automatically given whatever income beyond participant premiums that it needs, from government revenues. The HI portion of Medicare, financed similarly to Social Security’s trust funds, is starting its drawdown. Medicare’s HI trust fund will begin diminishing this year (see Figure 2, reproduced directly from the trustees’ reports), and be depleted by 2026. As with Figure 1, Figure 2 shows Medicare HI’s reserves drawn down to the depletion point, and its unfunded obligations afterward.

Figure 2: Projected Drawdown of Medicare HI Reserve Balances

(Figure III.B5 from Medicare Trustees Report)

The significance of this year’s turning point is not that there will be any immediate impact on beneficiaries. There won’t –not yet. It is that both Social Security and Medicare are beginning their trust fund drawdowns far sooner than was projected just last year. In last year’s reports, the combined Social Security trust funds were not projected to hit this point until 2022, and the Medicare HI trust fund not until 2023.

It is not unusual for long-term projections, like trust fund depletion dates, to move around by several years from one year’s reports to the next. But it is exceptional for one year’s reports to project that the two programs will each reach an adverse financial milestone in 5-6 years, only to be followed the very next year by a revised projection in which they both hit it in the current year.

What happened? Several things, but the biggest factor was a reduction in payroll tax revenue. Revisions of data for 2016 and 2017 resulted in a worsened starting point for both programs’ income in 2018. The Social Security report explains, albeit in highly technical language:

“First, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) published revised data in July 2017 showing that the ratio of labor compensation to GDP for 2016 was 2.1 percent below the level used for the 2017 report. BEA also published data for 2017 indicating that the ratio of labor compensation to GDP was 3.1 percent below the level projected for the 2017 report. Second, based on a complete year of IRS earnings data, the ratio of OASDI effective taxable payroll to GDP for 2016 was 1.7 percent below the level projected for the 2017 report. Based on IRS data through the first half of 2017, the ratio of OASDI effective taxable payroll to GDP for 2017 is now estimated to be 2.0 percent lower than projected for the 2017 report.”

Translated, worker compensation and taxable wages in 2016 and 2017 weren’t what the trustees believed they were, so the programs’ 2018 tax base is smaller than previously projected. This means less payroll tax revenue for each program. The trustees now project $883 billion in Social Security payroll tax revenue for 2018, as compared with last year’s projection of $928 billion. This is the biggest reason that $45 billion in previously projected trust fund growth now appears as a $2 trillion loss to the funds.

Similarly, Medicare HI had been projected last year to receive $282 billion in payroll tax revenue in 2018, a projection now reduced to $268 billion. This $14 billion downward revision is the biggest reason previously expected growth of $17 billion in the Medicare HI trust fund is now projected to be a $5 trillion loss. (Other lesser factors on the Medicare side include lower than projected income tax revenue and higher than projected program expenditures, each of which contributed about $3 billion to the net projection change.)

The big consequence of all this is that Medicare’s finances are now very shaky. There are only about eight months’ worth of benefit payments in the Medicare HI trust fund, meaning there is very little room for further depletion. The trustees project that the fund would be completely depleted by 2026, at which time Medicare HI could only make 91% of insurance payments, gradually declining to 78% in 2039.

The worsened starting point also increases the size of the changes required to restore Medicare HI to long-term balance. The estimated long-term HI imbalance in the 2018 report is 0.82% of national taxable wages, substantially higher than 0.64% of taxable wages as projected last year.

There has been speculation as to the extent to which recent legislation has worsened the Medicare outlook. The answer is: some, but it’s not the big factor. Of all the factors cited by the Medicare trustees as negative contributors to the outlook, the sum total of all recent legislation (including repeal of the Medicare Independent Payment Advisory Board and the ACA’s individual health insurance mandate) amounted to just a little over one-quarter of the negative influences. The aforementioned changes to the starting values are comparatively much more significant.

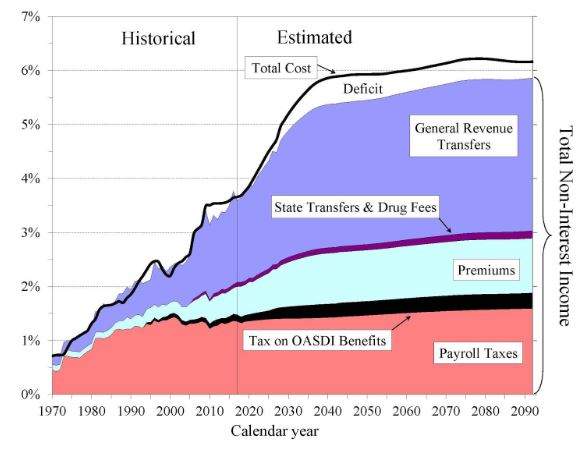

Again, HI is only one part of Medicare, and a lesser part at that. Costs in Medicare’s SMI trust fund, three-quarters of which is financed from the federal government’s general fund, are projected to grow from 2.1% of GDP in 2017 to 3.6% of GDP by 2037, placing enormous additional pressure on the federal budget. Figure 3, taken from the trustees’ report summary, dramatizes the growth of the general revenues required to finance Medicare SMI.

Figure 3: Total Medicare Cost and Income as a Percentage of GDP

(Chart C from the Trustees’ Report Summary)

On the Social Security side, the worsened starting point is partially offset by some more optimistic assumptions going forward, particularly with respect to disability insurance. Disability applications and awards have dropped as the labor market recovered from the Great Recession. The trustees also find that average disability benefit award levels are below previous projections, which they have incorporated into their revised projections going forward.

All the changes add up to very little with respect to Social Security’s long-term actuarial balance. The story there is the same as it has been for several years: bad and getting worse. Social Security’s long-term shortfall of 2.84% of taxable worker wages is already far larger than the one solved in the landmark 1983 reforms, and with every passing year it grows more difficult to correct. The trustees calculate that if the shortfall were closed by prospective benefit reductions, they would have to average 21% across the board.

Given the political implausibility of cutting one-fifth of the US population entirely off from Social Security benefits, far more Americans than that will be affected when the necessary corrections eventually take place. We have already moved deeply into a realm in which corrections must now adversely affect many economically vulnerable Americans. These Americans have been done no favors by irresponsible politicians claiming that Social Security is best safeguarded by leaving its benefit and revenue schedules alone.

We should have repaired the Social Security and Medicare ships’ hulls long before they started taking on water. It’s about to get much more difficult for the vulnerable passengers onboard if lawmakers do not act soon.

Charles Blahous, a contributor to E21, holds the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair at the Mercatus Center and is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.