by Christine Vestal

Repeatedly rated one of the healthiest and happiest places to live in the United States, this medium-sized college town with spectacular views of the Blue Ridge Mountains tends to attract entrepreneurs, freelancers and creative types who can live anywhere they want because they’re not tied to a corporate job.

But this year, many of those untethered workers may be wishing they lived anywhere but here. Residents of Charlottesville and three surrounding counties who buy health insurance without employer support or government subsidies have been hit with the highest health insurance premiums in the country — more than three times the price they paid last year.

Premiums are also substantially higher than average, although not as high as in Charlottesville, in southwestern rural Georgia, certain Colorado ski resort towns, the Connecticut suburbs of New York City, and large parts of Wisconsin and Wyoming, among other places.

Charlottesville’s premium spike may be an anomaly. But insurance experts say it could be an indication of what might happen in other parts of the country next fall, when insurers post their final rates for 2019.

Nationwide, premiums for average-priced policies — according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis — offered on and off the health insurance exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act rose by more than a third compared with 2017. The biggest statewide hikes were in Iowa (88 percent), Utah (78 percent), New Hampshire (78 percent), Wyoming (72 percent), and Virginia (66 percent).

The underlying cause of the rate hikes is clear: efforts last year by the Trump administration and its allies in Congress to dismantle the Affordable Care Act — and promises of further attempts in the year ahead.

“It all added up to chaos and uncertainty in the insurance market,” said Sabrina Corlette, a Georgetown University research professor and insurance expert. “And uncertainty always leads to higher premiums.”

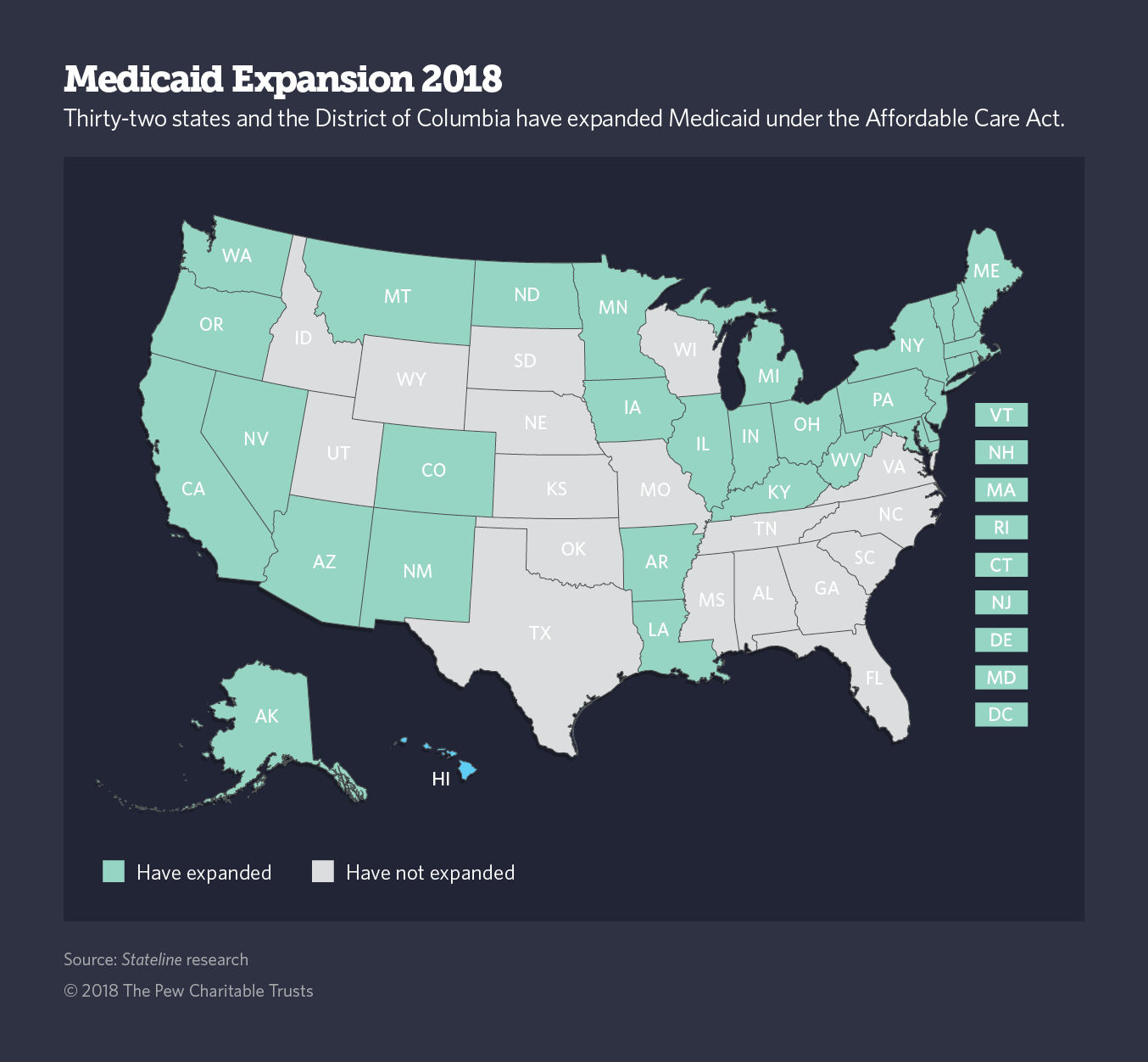

This year, a handful of Democratic-led states are gearing up to curb further rate hikes by enacting laws and adopting insurance regulations designed to shore up the traditional insurance industry and restore parts of the ACA, known as Obamacare.

At the same time, at least one Republican-leaning state has moved to further unravel the federal health law by encouraging insurance companies to offer cheap policies with fewer benefits. Others are expected to follow.

Both red and blue states are reacting to a series of federal actions.

The federal tax overhaul enacted in December repealed the individual mandate, which required everybody to have health insurance or pay a financial penalty. The requirement was designed to ensure that healthy people signed up for insurance so that premiums for everyone remained affordable.

Two months earlier, President Donald Trump withdrew billions in federal insurance industry subsidies that allowed insurers to keep premiums affordable while holding down copays and deductibles.

Around the same time, Trump also cut the health exchange enrollment period in half. And earlier in the year, he slashed the marketing budget for federal exchanges to further damage the health law by curtailing enrollment.

This year, both branches of government promise further attacks on the health law, including final actions on two administration proposals. One would encourage insurers to offer short-term policies with variable copays and deductibles, and the other would allow people to form groups to create so-called association health plans with cheap premiums and limited benefits.

In Idaho, Republican Gov. Butch Otter followed the administration’s cues, signing an executive order this month that directs the state insurance agency to draft rules allowing insurance companies to offer cheap plans with stripped-down benefits.

Going in the opposite direction, California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia and Maryland are considering legislation that would recreate the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate by requiring nearly all residents to enroll in a health plan or pay a fee. Massachusetts has a mandate on the books that it said it intends to enforce.

Taking a different tack — one that has been endorsed by members of both political parties — Alaska, Minnesota and Oregon have created so-called reinsurance programs designed to cover higher-than-average claims with state money and thereby reduce overall risk for insurance companies so they can offer consumers lower premiums.

Under the health law, the federal government can reimburse states for any money spent on reinsurance programs that results in lower premiums, and thus reduced federal tax subsidies, as long as the reimbursements do not exceed federal savings. Washington state and Wisconsin are considering similar programs this year.

In New Jersey, newly elected Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy signed an executive order this month directing state agencies to invest in greater outreach and education to encourage more people to sign up for coverage on the state insurance exchange when it opens in November. California and New York launched similar advertising and marketing campaigns last year for the same reason.

By encouraging more people to enroll, states can improve the odds that their insurance markets will stabilize and premiums will remain affordable.

“Consumers are still confused about health insurance subsidies, and they’re hearing a lot of bad news about the ACA,” said Sarah Lueck, an insurance analyst at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “States need to tell consumers that the market isn’t crumbling, because it’s not. There are still some really good deals out there.”

It’s too early to know how many other states will move this year to fill the policy gaps in the tattered Affordable Care Act. But consumer advocates are urging lawmakers and governors to act sooner rather than later.

“States need to prepare now if their initiatives are going to have the desired effect,” Lueck said. If states want to stabilize the insurance industry by establishing individual mandates or reinsurance programs, they need to have their policies in place before spring and summer, when companies are required to file preliminary rates for 2019, she said.

For states that want to follow New Jersey’s lead and beef up outreach and marketing for their insurance exchanges this year, there’s a little more time. Insurance exchange marketing typically doesn’t start until September, two months prior to open enrollment in November.

But there’s another approach states can take at any time to protect their traditional insurance markets from the continued uncertainty created by attacks on the ACA from Congress and the Trump administration.

Once federal agencies finalize rules allowing cheaper, substandard health policies, states can prohibit those policies from being sold within their borders unless they comply with ACA consumer protections, according to a recent article by a group of consumer advocates in the policy journal Health Affairs.

New Jersey and New York already have such prohibitions, and Minnesota allows non-complying health plans to be sold only under limited circumstances.

Unsubsidized Consumers

Before the Affordable Care Act took effect in 2014, people who were self-employed, between jobs or working part time and were not offered employer-sponsored health plans typically had to pay the highest prices for health coverage because insurers considered the relatively small pool of individuals riskier than larger groups.

Many people who faced high-priced individual insurance policies took their chances and went without coverage. Others opted for cheaper plans with high out-of-pocket expenses and limited benefits.

For this group, the ACA’s consumer protections were a huge boon. Confident they could find affordable health insurance, many workers were able to strike out on their own for the first time.

Insurers were prohibited from refusing coverage to people with pre-existing conditions or charging people higher premiums because of their medical history. And although individual market premiums still tended to be higher than group plans, rates and coverage improved in the first four years after the federal health law took effect.

But last year’s revisions to the law may have changed all that.

As a result, many states can be expected to take action this year to protect this group of consumers from unreasonably high insurance premiums, said Timothy Jost, a retired law professor at Washington and Lee University in Virginia and an ACA expert. They will either be propping up the ACA and the traditional health insurance market, or further undermining the federal health law by promoting cheaper, lower quality policies, he said.

The result, he said, will be even greater disparities than already exist between states in the number of people who can afford quality health care coverage.

In fact, the Trump administration’s tactics are likely to bolster the overall proportion of Americans enrolled in Medicaid and federally subsidized exchange policies, said Joel Ario, a health care analyst with the law firm Manatt, Phelps and Phillips who worked in the Obama administration. That’s because the policies will remain affordable and people will enroll in them even without the coercion of the individual mandate, he said.

Left out will be people not covered by employer-sponsored insurance and with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid or federal exchange subsidies. Nationwide, about 22 million people purchase insurance in the individual market, according to Kaiser. About 43 percent of them have incomes too high to qualify for federal tax subsidies on the exchange.

Charlottesville resident Sara Stovall is among them. She, and fellow residents Ian Dixon and Karl Quist, have hired an attorney to represent them and a group of more than 700 other locals who in November were hit with exorbitant premiums. They’re arguing in a case before the Virginia Insurance Bureau that the rates filed by Optima Health — a Virginia-based insurance carrier and the sole remaining provider of health coverage in their area — violated federal law.

But even if they win the case and the state orders Optima to issue refunds, they and the others in their group won’t personally benefit. The money would go to a regional insurance pool and ultimately would be deducted from future premiums for all policies.

Stovall, Dixon and Quist, all of whom had incomes just above the federal limit, could not afford their 2018 insurance premiums, roughly $3,000 a month for a family of four. Stovall, whose husband’s freelance photography business is growing, said their premiums would have been more than their mortgage payment.

Dixon, a self-employed software developer, said he and his family moved from Washington, D.C., to Charlottesville two-and-a-half years ago, when he quit his day job. “I heard there was a good startup community here,” he said. “But if individual insurance rates had spiked that year like they did this year, we never would have come here.”

Christine Vestal covers health care for Stateline.