The Economist

A Texan border city offers a case study in the perils of populism

If it is scary, it must be coming over the border with Mexico. That principle has long guided border-security populists. Beto O’Rourke, a Democratic congressman for El Paso, a Texan border city, recalls a 1981 headline from the El Paso Herald-Post, about border checks for a Libyan hit squad that was supposedly coming to America. The assassins were never found. “Whatever the threat of the day is, we tend to project it onto the border,” says Mr O’Rourke. Today, the rumour is that Islamic State (IS) terrorists are lurking in Ciudad Juárez, just across the Rio Grande from El Paso, and plotting to attack America. This tale is spread by internet conspiracy-mongers and politicians big enough to know better.

The Republican governor of Texas and a putative presidential contender, Rick Perry, accuses the Obama government of paying “lip service” to border security, creating a “very real possibility” that IS or other terror groups have already crossed from Mexico. Another Texan with national ambitions, Senator Ted Cruz, says that securing the Mexican border should come “first and foremost” in any plan to fight IS worldwide, citing reports of online chatter among suspected militants about the possibility of crossing that frontier.

In vain, Homeland Security officials say that they have no credible information pointing to such plots, and that arrivals on commercial flights are a bigger worry. Ahead of mid-term elections in November, Senate candidates as far afield as Georgia and New Hampshire are running doom-laden TV attack ads, linking the menace of radical Islam to demands for Mr Obama and Democrats to “secure the border”.

Lexington spent two days on the border this month, around the anniversary of September 11th, 2001. The fruits of fearmongering were visible to the naked eye. The bridges and inspection lanes linking El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, which are normally clogged with traffic, were largely deserted. Rumour-peddlers in El Paso insisted that the border had been placed on high alert. Puzzled officers knew of no such alert—though they knew all about public alarm. A burly border guard told of ordering his tearful son to school on September 11th, over the boy’s fears of terror attacks.

Bringing border traffic to a standstill is no small thing. El Paso and its Mexican twin are so close that (except during drug wars) Texans often stroll across the line to visit the dentist or a cheap pharmacy. Mexican daytrippers head north in their millions every year, buying cheap clothes and household goods in El Paso’s shops. Conspicuous in crisp white and blue uniforms, gaggles of Mexican children walk to American private schools each morning. Other bridges carry rumbling lorries and mournfully-hooting trains—laden with flat-screen TVs or car parts from Mexican maquiladoras, but also American-made machines and components heading south. Mexico is the second-largest market for American exports, supporting an estimated 6m gringo jobs.

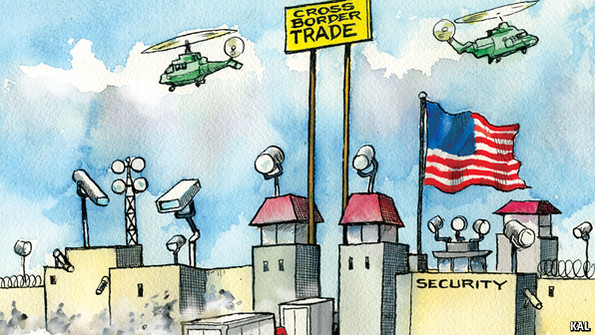

Since 2001 Congress has thrown tens of billions of dollars at the border. Different agencies were merged to create a behemoth, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), with Border Patrol agents (quasi-paramilitaries in green uniforms) guarding the frontier, and CBP officers (in dark blue) to man air, land and sea ports of entry, screening hundreds of millions of passengers and trade flows worth trillions of dollars. In Washington, DC, border debates always focus on illegal migration, notes Bill Owens, a congressman whose New York district abuts dangerous Canada. So “money gets thrown at the green uniforms”.

The number of patrol agents has doubled in a decade, to more than 21,000 (the same size as the active-duty Canadian army). Hundreds of miles of fencing have been built, buttressed by sensors, cameras, surveillance blimps, helicopters, drones and patrol planes. Apprehensions have neared record lows in recent years: the average agent catches less than one person a fortnight. Yet most people in Congress want still more agents in green.

For years investment in legal border crossings and blue uniforms badly lagged, even as passenger numbers and trade flows grew. In El Paso recently, a forum of business bosses, mayors, border congressmen and bigwigs from the Department of Commerce sounded the alarm about congestion and creaking infrastructure at border ports. Odd business practices already show how delays hurt trade. Some firms will rush lorries through the border half-empty, if they fear long queues. With several new car factories planned in Mexico, some sea ports, such as San Diego in California, are proposing to ship vehicles around snarled land crossings and highways in short hops.

You say border security, I say bottleneck

Dysfunction in Washington is spurring innovation. Mr O’Rourke, working with a few business-friendly Texas Republicans, helped pass a law allowing El Paso and a few other pilot cities and airports to pay overtime for CBP officers in peak periods. CBP commanders insist that they are trying to speed goods through, for instance with fast lanes for trusted shippers, while keeping to their primary post-2001 mission—hunting terrorists and weapons of mass destruction. Some border-district members of Congress and Commerce Department bosses have begun a Heartland Outreach Tour, telling Chambers of Commerce or factory workers in inland America how much their state exports to Mexico and Canada, hoping that they will press Congress to see the border as a place of opportunity. Some argue for donating queue-busting customs technology to Mexico.

Building a more rational border will take an alliance between pro-trade Democrats and pragmatic, non-nativist Republicans. That is a shrinking pool. More lawmakers like Mr O’Rourke, an internet entrepreneur by background, who clashes frequently with border populists in Congress, would help. Shouting about deadly foreigners is sexier than trying to cut the costs of cross-border supply chains. But the latter would make America richer.