While off-road vehicle maker Polaris benefits from moving some production south of the border, Trump’s levy proposal is primed to add millions in costs.

By John Keilman, WSJ

More than a decade ago, the off-road vehicle maker Polaris surrendered its status as a 100% made-in-America company, gambling that it could add a Mexican factory without alienating customers.

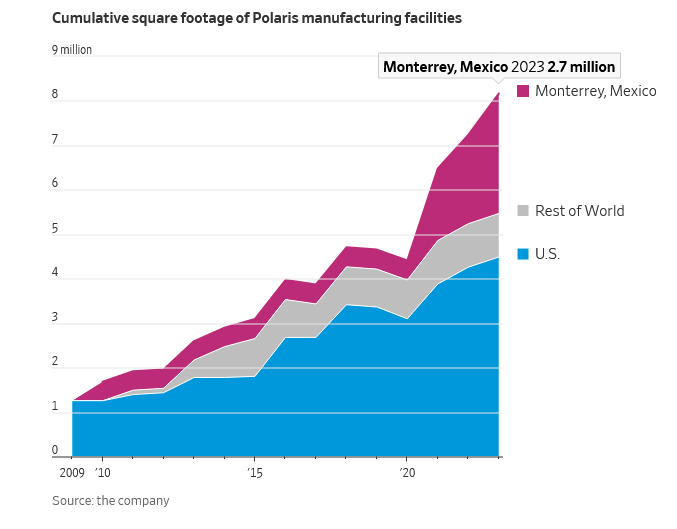

The move paid off handsomely. Buyers didn’t flinch as the plant, located in Monterrey, churned out more than 22,000 vehicles in its first year, helping to expand the company’s sales 33% while saving millions of dollars in costs. The factory has since become Polaris’s largest, producing such models as the RZR, a dune buggy-like vehicle that starts at $16,000 and can reach over $40,000.

Now the plant could become a liability. President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to levy a 25% tariff on all goods coming from Mexico as retribution for what he described as the country’s lax efforts in stopping drug smuggling and illegal immigration.

For Polaris, which has added engine-assembly and injection-molding facilities to its Monterrey operations, the new duties could create $400 million in costs that would be passed on to consumers, according to David MacGregor of Longbow Research.

The higher prices would come as Polaris faces weaker demand for its products, as well as $70 million to $80 million in tariffs for Chinese components used in its U.S.-made vehicles. The company has argued that those tariffs, put in place during Trump’s first administration, are an unfair burden because its top competitors don’t manufacture in the U.S.

Speaking at an investor conference Wednesday, Chief Executive Michael Speetzen said Polaris is reviewing its sourcing but otherwise is waiting to see what happens.

“We’re not going to spend a lot of energy trying to worry about what could be,” he said. “I mean, there’s a million different scenarios.”

Tariffs would upend a trade relationship that since 1994 has allowed most goods produced in Mexico to enter the U.S. duty-free. Companies making everything from cars to medical devices have taken advantage of the country’s proximity to the U.S. and its abundant, less expensive labor. Last year Mexico exported $475 billion of goods to the U.S., surpassing China to become the biggest foreign supplier.

Companies including Minnesota-based Polaris are now pondering an abrupt adjustment to their longstanding economic calculus. The Motorcycle Industry Council, which lobbies for power-sports manufacturers, said high tariffs would be damaging to the industry and its customers.

“We hope that any new tariffs will also come with an opportunity to make our case for exclusions,” said Scott Schloegel, a senior vice president at the trade group.

Heading south

Polaris’s founders built their first vehicle, a snowmobile, in the 1950s, and for years the company’s sole plant was in Roseau, Minn., a rural town about 10 miles south of the Canadian border. It later added factories in Iowa and Wisconsin. For more than a decade after the North American Free Trade Agreement sent U.S. manufacturers flocking to Mexico, the company stood pat, insisting that its Midwestern workforce was sufficiently cost-effective.

That sentiment changed in 2010. Scott Wine, who was chief executive at the time, announced plans to build a factory in Mexico, saying Polaris would save more than $30 million a year in production costs and produce off-road vehicles closer to its customer base in the southern U.S.

Another advantage: While Polaris had trouble attracting workers to the small towns hosting its U.S. factories, that wasn’t an issue in the industrial hub of Monterrey. Its metropolitan-area population of 5.3 million is nearly as large as the entire state of Minnesota.

“It’s still only a couple hours outside of the border, and we will get a significant savings and more efficiency and faster speed throughout our value chain once this is fully up and running,” Wine said at an investment conference.

Polaris built its factory on the eastern edge of the metro area, not far from the airport. The process wasn’t smooth. The company had to build a supply chain from scratch. There was also occasional violence in the city, and at one point a model vehicle shipped from Minnesota was stolen in transit, according to people familiar with the matter. But within a year, production had begun.

Polaris has since expanded its product lines and global ambitions, adding factories in China, Poland and France, along with Alabama and Indiana. It still employs more people in the U.S. than it does in Mexico, but the company’s Monterrey facilities have become its biggest by far, covering 2.7 million square feet.

‘What are you going to do?’

After the factory opened, Polaris said customers didn’t push back. The company stopped placing American flag decals on vehicles, a subtle sign of the shift.

Eugene Bass, a 54-year-old general contractor from Delta Junction, Alaska, owns a RZR and captures some of his rides on a YouTube channel. He said he would prefer if the vehicle had been made in the U.S. but isn’t put off by its Mexican origin. Off-roading is so exhilarating, he said, that many drivers likely wouldn’t be deterred by a tariff-related price hike.

“I think you’ll see a lot of people hemming and hawing about it, but you know, they’re going to buy them anyway,” said Bass, who paid more than $30,000 for his 2022 model. “It’s just like the price of everything else going up. What are you going to do?”

The U.S. and Mexico imposed tariffs on each other during Trump’s first term before arriving at a successor pact to Nafta known as the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. It allowed most products, including Polaris’s, to remain duty-free. But the president-elect is promising a more aggressive stance this time around, threatening the farm equipment maker Deere with a 200% tariff if it moves production to Mexico.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum promised retaliatory tariffs if Trump proceeds with his plan.

Some supply-chain specialists doubt that Trump administration tariffs will reverse manufacturing’s long-running investment in Mexico, adding that even the conflicts of Trump’s first term didn’t derail the sector’s growth.

“It’s too big to stop,” said Eric Porras, a professor at the Egade Business School at Tecnológico de Monterrey. “Two or three years of this pressure from the U.S. might not be equivalent to the more than 20 years that we have been exchanging goods.”

.

.