The only people who can be both easily rounded up and deported without a court hearing are those who have already been ordered removed from the United States but are allowed to stay if they come in for regular check-ins.

If you didn’t think they were serious before, you certainly ought to know better now.

Donald Trump’s team has construed his victory as a mandate for carrying out what it has described as mass deportations. Even before Mr. Trump announced a nominee to lead the Department of Homeland Security, he named Stephen Miller, an immigration hard-liner, as deputy chief of staff and homeland security adviser, and Tom Homan (who was the acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement during part of Mr. Trump’s first term) as a White House-based czar to oversee “all deportation of illegal aliens back to their country of origin.”

It is tempting to assume that after his first term and four more years of planning, Mr. Trump and his administration will find no obstacles to impose their will swiftly and completely.

But that’s not true. No executive order can override the laws of physics and create, in the blink of an eye, staff and facilities where none existed. The constraints on a mass deportation operation are logistical more than legal. Deporting one million people a year would cost an annual average of $88 billion, and a one-time effort to deport the full unauthorized population of 11 million would cost many times that — and it’s difficult to imagine how long it would take.

So the question is not whether mass deportation will happen. It’s how big Mr. Trump and his administration will go, and how quickly. How many resources — exactly how much, for example, in the way of emergency military funding — are they willing and able to marshal toward the effort? How far are they willing to bend or break the rules to make their numbers?

The details matter not only because every deportation represents a life disrupted (and usually more than one, since no immigrant is an island). They matter precisely because the Trump administration will not round up millions of immigrants on Jan. 20. Millions of people will wake up on Jan. 21 not knowing exactly what comes next for them — and the more accurate the press and the public can be about the scope and scale of deportation efforts, the better able immigrants and their communities will be to prepare for what might be coming and try to find ways to throw sand in the gears.

Understand, first of all, that no change is needed to U.S. law to start the deportation process for every unauthorized immigrant in the United States. Being in the country without proper immigration status is a civil violation, and deportation is considered the civil penalty for it. Just as he did during his first term, Mr. Trump will almost certainly issue guidance to Immigration and Customs Enforcement that every unauthorized immigrant is fair game for arrest, and that deportable immigrants who happen to get caught up by ICE, even if agents aren’t specifically looking for that person, could also be detained.

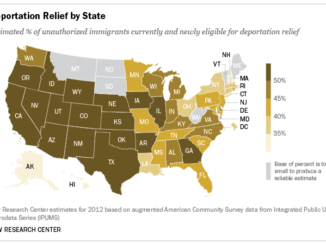

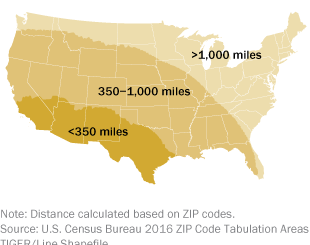

ICE agents already have authority to conduct enforcement in residential and commercial areas; the reason they usually haven’t (even under Mr. Trump) is because those raids take a lot of planning for the frequently low numbers of people they actually nab. It requires far less effort to simply pick up immigrants from local jails, which is why ICE tends to prefer working with local law enforcement. Since some local police are more willing to cooperate than others, this makes deportation risk a matter of geography.

But the arrest of immigrants isn’t the same as their removal.

For most immigrants — those who haven’t been apprehended shortly after their arrival — deportation isn’t a quick process. It generally entails the right to a hearing before an immigration judge, to prove that the immigrants lack legal status and that they can’t apply for relief (such as asylum). In the meantime, they’re either released on supervision or held in immigration detention.

In fiscal year 2024, Congress gave ICE the money for 41,500 detention beds. This is insufficient for anything that would constitute mass deportation. Extra holding facilities can be spun up as needed, but not immediately — and at higher cost (because of, say, noncompetitive contractor bids) than building a detention facility the usual way.

Immigration courts are famously backlogged, not least because that’s where asylum-seekers end up to present their cases. (An initial screening at the border can weed out some asylum claims, but frequently — especially under the Biden administration — bottlenecks at the screening stage can get fixed by skipping people straight to the no-less-bottlenecked immigration court stage.) As of the end of September, 3.7 million people were waiting for their claims to be resolved. This includes an overwhelming majority of the recent border crossers whose arrival under President Biden so incensed Mr. Trump and his allies. They can try to rush their court cases through faster (though they’ll need people, meaning money, to do it), but there’s not much juice to squeeze in rounding up people who are already, legally speaking, in deportation proceedings.

The only people who can be both easily rounded up and deported without a court hearing are those who have already been ordered removed from the United States but are allowed to stay if they come in for regular check-ins. Indeed, those were some of the first people targeted in 2017. The problem there — and a problem for any mass deportation operation — is that many of these people were not immediately deported because their countries had not agreed to accept deportation flights from the United States, or had limited the number of deportees they would accept. Mr. Trump has no problem using any diplomatic cudgel available to get other countries to cooperate on immigration enforcement. But it’s going to be tricky to argue simultaneously that, say, the United States is in some sort of conflict with Venezuela that would somehow allow for the deportation of its nationals through the activation of the Alien Enemies Act (which requires a declared war or an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” by a foreign government), and also that Venezuela must bend the knee and allow large numbers of deportation flights onto its soil.

Who gets targeted first — who is most at risk in the days after a second Trump inauguration — will depend in part on which of these problems the administration tackles first. If Trump officials get a diplomatic breakthrough with a country previously deemed recalcitrant, expect large numbers of people to get arrested at their ICE check-ins and deported under existing removal orders. If they don’t, expect deportations to be limited to countries that are generally already willing to take U.S. removal flights (like Mexico, Guatemala, Peru). People with prior contact with the criminal justice system are politically appealing targets, but if they haven’t already been deported, it may be because their cases are complicated and will need to be worked out in court. People who have a form of legal status that has lapsed, or legal protections that the Trump administration might try to strip, such as Temporary Protected Status, may be easy to find but won’t be quick to remove.

Many Trump critics are liable to wave off such considerations, because they assume that a second Trump administration will have no problem breaking the law en masse to deport large numbers of people. Even if true, that doesn’t exempt them from the logistical realities: beds in detention, seats on planes.

That this mass deportation will happen with no legal restraints, accountability or oversight is by no means a premise to be granted without contest. Because resigning oneself in advance to a maximalist vision of mass deportation helps accomplish the same goal: making immigrants feel they have no choice but to leave the United States.

There are two previous occasions in which the U.S. federal government can be said to have engaged in mass deportation — around the 1930s and the 1950s. Both entailed horrific conditions for those caught and deported, and the tearing apart of families with claims to both the United States and other countries. But in both cases, the federal government ultimately took credit for “deporting” some people it never actually laid hands on — those who had been pressured or terrorized into leaving.

In the 1930s, high-profile raids in Los Angeles didn’t net that many immigrants to deport — the real impact was in sending the message that raids might happen, leading some immigrants to pick up and leave and many more to stay home and out of the public eye. In 1954 and 1955, the so-called Operation Wetback probably arrested and removed fewer immigrants than had been removed the year before — historians think of it as a retroactive P.R. campaign for the previous year’s efforts, but one that had effects of its own. In the first month of Operation Wetback, one historian estimates, 60,000 immigrants left Texas voluntarily — about as many as the government apprehended throughout the country per month.

For those who believe the United States will be better off if every unauthorized immigrant leaves the country — no matter how many native-born U.S. citizen children they have to take with them to keep families together or how many American communities are surveilled and disrupted for years — making people afraid enough to deport themselves is a convenient and low-cost way to do it.

Conversely, those who do not wish to see millions of people leave the United States under coercion during a second Trump administration should do what they can to prevent that reality. That starts with a committed and cleareyed understanding of what is actually happening, and a willingness to treat abuses of power as a rupture and an aberration — something that can, and should, be fought.

They can document and communicate when the government is breaking the law; pressure state and local officials to refuse to collaborate with federal removal efforts by refusing to share information, and especially by objecting to deployment of the military or National Guard in their states’ territory; and support efforts to provide legal representation to immigrants.

This work will require, particularly for those who are not themselves immigrants, a promise not to let pessimism do the Trump administration’s job for it. The government will do things that hurt people. It will do things that look scary.

But how many people will be caught up in a deportation machine, and how quickly, is by no means a settled question — and it’s one that a public sympathetic to immigrants should continue to care about the answer to.

.

Dara Lind is a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council.

.