The threat of being cut out of a trade agreement was more imagined than real — the Trump administration could not replace NAFTA with a bilateral arrangement without congressional approval — but Canada still had to move quickly to restore a trilateral solution.

by Asa McKercher and Adam Chapnick

United States President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to implement an across-the-board tariff of at least 10 per cent on all imports into the country.

While there could be some exemptions for American imports of oil, gas and other natural resources, it’s not yet clear whether Canada will be protected by the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA).

In fact, when the deal comes up for a mandatory review in 2026, Trump has said: “I’m going to have a lot of fun.”

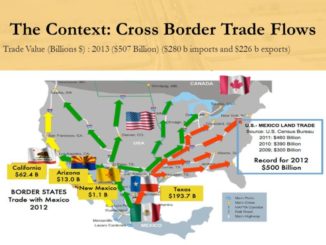

Given that more than 77 per cent of Canada’s exports go to the United States, Canadians have understandably viewed Trump’s declarations with alarm.

And against the likely torrent of American protectionism, Canada has few good options. Responding in kind, for example, will likely lead to a rise in inflation.

Kicking out Mexico?

One idea, recently floated by Ontario Premier Doug Ford, is to abandon CUSMA’s trilateral framework and seek a bilateral Canada-U.S. trade deal. As Ford put it: “We must prioritize the closest economic partnership on Earth by directly negotiating a bilateral U.S.-Canada free trade agreement.”

The premier’s specific complaint is that the Mexican government has failed to prevent the trans-shipment of Chinese goods — especially auto parts and vehicles — through its country in order subvert tariffs imposed by the American and Canadian governments against China.

If Mexico won’t act to prevent trans-shipments or impose its own tariffs on Chinese goods, Ford explained, “they shouldn’t have a seat at the table or enjoy access to the largest economy in the world.”

Ford’s comments drew immediate criticism from Mexican trade officials, but Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s deputy prime minister and finance minister, was more sympathetic. Concerns about Mexican handling of Chinese goods “are legitimate concerns for our American partners and neighbours to have. Those are concerns that I share,” she said.

This is not the first time Canadians have expressed wariness about including Mexico in common North American arrangements.

Canada’s position on Mexico

In 1956, when U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposed a trilateral summit with Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent and Mexican President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines, Canadian diplomats expressed their opposition to anything that “would appear to equate the relations between the United States and Canada and the United States and Mexico.”

For Ottawa, it was essential to preserve the notion of a special relationship between Canada and the U.S.

Even though the three leaders eventually met in Warm Springs, Ga., the “summit” ultimately consisted of separate U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico bilateral meetings.

Four decades later, Canada pressed to be included in what became the North American Free Trade Agreeement — known as NAFTA — not because of any fellowship with Mexico, but to ensure that its newly won market access to the United States (thanks to the 1988 Free Trade Agreement between the U.S. and Canada) was not undercut by a bilateral Mexico-U.S. deal.

Common front?

As we document in our new book, Canada First, Not Canada Alone, even if Canada’s suspicions of Mexico about trade matters aren’t out of the ordinary, they must be considered against the notion that in dealing with the U.S., there can be strength in numbers.

Throughout the early phase of the CUSMA negotiations during the first Trump presidency, Freeland herself was adamant that Canada not abandon Mexico in favour of a bilateral deal.

Rather, she pointedly emphasized the need to work alongside Mexico to present a common front against the Trump administration’s efforts divide its two North American trading partners.

When faced with an overwhelming aggressor, she argued, it’s best not to stand alone.

U.S. made side deal

This position was backed by other ministers as well as by Ottawa’s trade negotiators even as prominent Canadians — including former prime minister Stephen Harper — called for ditching the Mexicans.

At first, the Canadian approach appeared to succeed. Freeland herself earned a fearsome reputation among American officials, with Trump attacking her as a “nasty woman.”

Later, however, Canadian negotiators thought they saw an opening and offered the Americans a bilateral deal without notifying their Mexican colleagues.

Not only did Washington reject the offer, American officials approached Mexico City and concluded a separate side deal of their own. This time, it was Canada left unaware.

Warning signs

The threat of being cut out of a trade agreement was more imagined than real — the Trump administration could not replace NAFTA with a bilateral arrangement without congressional approval — but Canada still had to move quickly to restore a trilateral solution.

CUSMA subsequently came into effect on July 1, 2020.

The CUSMA negotiations should offer Ford and the entire Canadian negotiating team a warning.

If Canada is prepared to leave Mexico behind, Canadian officials should be prepared for their Mexican counterparts to do the same. And while it seems right now that the U.S. has problems with Mexico and its management of America’s porous southern border than it does with Ottawa, under the mercurial Trump, the situation can can change in an instant.

It’s therefore probably not in Canada’s interest to throw Mexico under the bus.

.

Asa McKercher (PhD, Cambridge) is Steven K. Hudson Research Chair in Canada-US Relations and an associate professor in the Department of Public Policy and Governance at St. Francis Xavier University.

Adam Chapnick is a Professor of Defence Studies, Royal Military College of Canada