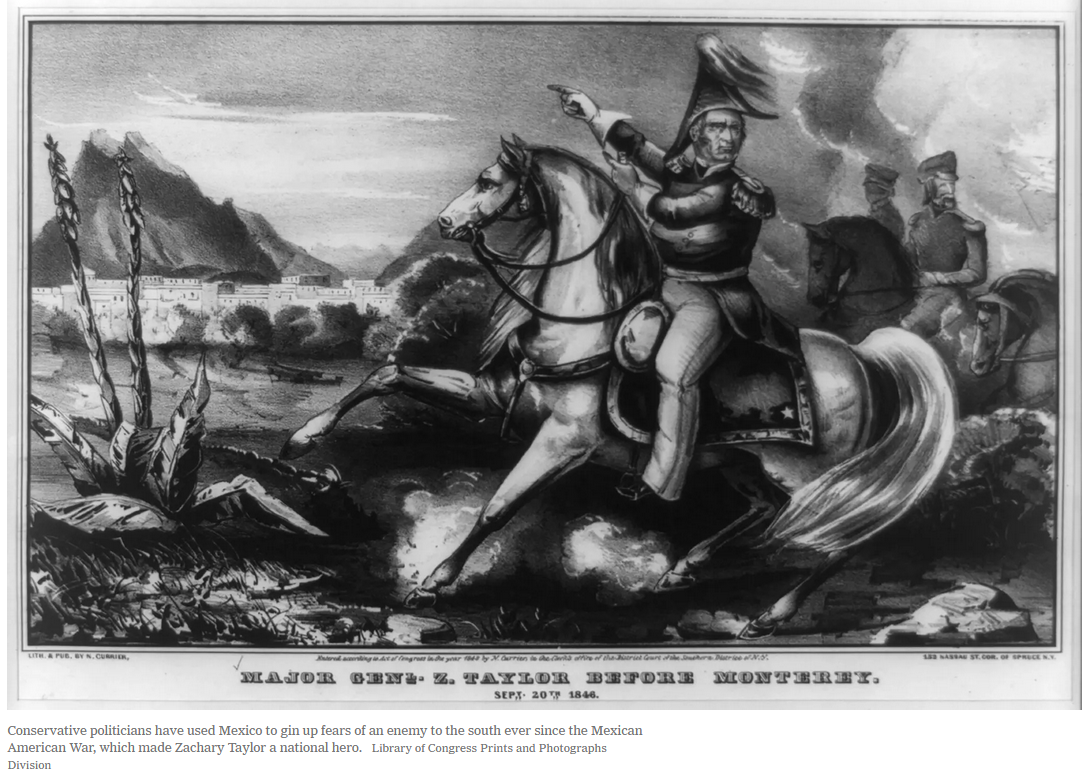

Conservative politicians have used Mexico to gin up fears of an enemy to the south ever since the Mexican American War.

by Greg Grandin

As president, Donald Trump reportedly floated the idea of shooting “missiles into Mexico to destroy the drug labs.” When his defense secretary, Mark Esper, raised various objections, he recalls that Mr. Trump responded by saying the bombing could be done “quietly”: “No one would know it was us.”

Well, word got out and the craze caught on. Now many professed rebel Republicans, such as Representatives Mike Waltz and Marjorie Taylor Greene, along with several old G.O.P. war horses, like Senator Lindsey Graham, want to bomb Mexico. Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida said he would send special forces into Mexico on “Day 1” of his presidency, targeting drug cartels and fentanyl labs. In May, Representative Michael McCaul, another Republican, introduced a bill pushing for fentanyl to be listed as a chemical weapon, like sarin gas, under the Chemical Weapons Convention. This move targeted Mexican cartels and Chinese companies, which are accused of providing the ingredients to the cartels to manufacture fentanyl.

Of course, the United States is already fighting, and has been for half a century, a highly militarized drug war — in the Andes, Central America and, yes, Mexico — a war as ineffective as it has been cruel. Hitting fentanyl labs won’t do anything to slow the bootlegged versions of the drug into the United States but could further destabilize northern Mexico and the borderlands, worsening the migrant refugee crisis.

Addiction to fentanyl, a drug that is 50 times stronger than heroin, affects red and blue states alike, from West Virginia to Maine, with overdoses annually killing tens of thousands of Americans. It’s a bipartisan crisis. Yet in our topsy-turvy culture wars, there’s a belief that fentanyl is targeting the Republican base. J.D. Vance rose to national fame in 2016 with a book that blamed the white rural poor’s cultural pathologies for their health crises, including drug addiction. In 2022, during his successful run for Ohio’s Senate seat, Mr. Vance, speaking with a right-wing conspiracy theorist, said that “if you wanted to kill a bunch of MAGA voters in the middle of the heartland, how better than to target them and their kids with this deadly fentanyl?” Mr. Vance’s poll numbers shot up after that, and other Republicans in close House and Senate races took up the issue, linking fentanyl deaths to Democratic policies on border security and crime and calling for military action against Mexico.

The Mexican government is in fact cooperating with the United States to limit the export of the drug, recently passing legislation limiting the import of chemicals required for its production and stepping up prosecution of fentanyl producers. And even some of the cartels have reportedly spread the message to their foot soldiers, telling them to stop producing the drug or face the consequences. Still, in a show of Trumpian excess, Mexico is depicted as the root of all our problems. Bombing Sinaloa in 2024 is what building a border wall was in 2016: political theatrics.

The United States is no novice when it comes to bombing Mexico. “A little more grape,” or ammunition, Gen. Zachary Taylor supposedly ordered as his men fired their cannons on Mexican troops. That was during America’s 1846-48 war on Mexico, which also included the assault on Veracruz, killing hundreds. Washington took more than half of Mexico’s territory during that conflict.

Reactionaries have fixated on the border for over a century, since before the Civil War, when Mexico provided asylum for runaway slaves. Over the years, newspapers and politicians have regularly demanded that Mexico be punished for any number of sins, from failing to protect property rights to providing refuge for escaped slaves, Indian raiders, cattle rustlers, bootleggers, smugglers, drug fiends, political radicals, draft dodgers and Japanese and German agents. There was a touch of evil about Mexico, as Orson Welles titled his 1958 film set on the borderlands.

Long before the Russian Revolution, hostility directed at the Mexican Revolution, which started in 1910, gave rise to a new, more militant, ideological conservatism. U.S. oilmen invested in Mexico blamed Jews for financing the revolution and raised money from U.S. Catholics to fund counterrevolutionaries, some of whom were fascists. From 1910 to 1920, private vigilante groups like the K.K.K., local police departments and the Texas Rangers conducted a reign of terror across the border states that killed several thousand ethnic Mexicans, some of whom were trying to organize a union or trying to vote.

Trumpism’s ginned-up racism against Mexicans flows from this history. It remains to be seen whether calls to bomb Mexico’s fentanyl labs will play well in the coming election cycle. Yet the rhetoric itself is a dangerous escalation of an old idea: that international narcotics production, trafficking and consumption can be deterred through military means.

Today’s Republican renegades say they represent a break from the “globalist” bipartisan consensus that governed the country through the Cold War and the decades that followed. But aside from some opposition to military aid to Ukraine, Republicans largely toe the line when it comes to the use of military force abroad. Few Republican dissidents dare question the establishment consensus on ongoing military aid to Israel, especially in light of its current siege of Gaza. In this sense, calls to bomb Mexico are a distraction, blowing smoke to hide the fact that the G.O.P. offers nothing new. Republicans certainly aren’t the peace party, as some of Mr. Trump’s isolationist backers would have us believe. All they offer is a shriller war party.

(As if to illustrate the point, as Republicans shout about Mexico, the Biden administration has quietly struck a deal with Ecuador that will allow the United States to deploy troops to the country and patrol the waters off its coast, the Washington Examiner recently reported.)

Even bombing another country in the name of fighting drugs is hardly innovative. In 1989, George H.W. Bush used the U.S. military to act on the federal indictment of Manuel Noriega, Panama’s ruler, for drug trafficking. In Operation Just Cause, the United States dropped hundreds of bombs on Panama City, including on one of its poorest neighborhoods, El Chorrillo, setting homes ablaze and killing an unknown number of its residents.

For all their posturing on how they represent a break with the past, today’s bomb-happy Republicans are merely calling for an expansion of policies already in place. Republicans have introduced legislation in the House and Senate that would in effect bind the war on drugs to the war on terrorism and give the president authority to strike deep into Mexico. Mr. Graham also says he wants “a Plan Mexico more lethal than Plan Colombia.”

Calls to inflict on Mexico something more lethal than Plan Colombia should chill the soul. Initiated by Bill Clinton in 1999, Plan Colombia and its successor strategies funneled roughly $12 billion into Colombia, mostly to security forces who were charged with eliminating cocaine production at its source. Their campaign included, yes, the aerial bombing of cocaine labs.

Conflict in Colombia is a longstanding phenomenon, but Plan Colombia helped kick off a wave of terror that killed tens of thousands of civilians and drove millions from their homes. The Colombian military murdered thousands of civilians and falsely reported them as guerrillas, as a way of boosting its body count to keep the funds flowing. Massacre followed massacre, often committed by the Colombian military working in tandem with paramilitaries. At the end of last year, Colombia had the fourth-largest population that was internally displaced because of conflict and violence, behind only Syria, Ukraine and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

For what? More Colombian acreage was planted with coca in 2022 than in 1999, a year before the start of Plan Colombia. Colombia remains the world’s largest cocaine producer.

Plan Colombia did weaken Colombian drug producers and disrupt transportation routes. But it also incentivized Central American and Mexican gangs and cartels to get in the game. Drug-related violence that had largely been confined to the Andes blasted up through the Central American isthmus into Mexico.

Then in 2006, with support from the Bush administration, Mexico’s new president, Felipe Calderón, did what today’s Republican would-be bombardiers want Mexico to do: declare war on the cartels. Again, the result was catastrophic. Estimates vary, but by the end of Mr. Calderón’s six-year term, about 60,000 Mexicans had been killed in drug-war-related violence. By 2011, an estimated 230,000 people had been displaced, and about half of them crossed the border into the United States. Tens of thousands of Mexicans, including social activists, were disappeared, or had gone missing. The cartels, meanwhile, grew more profitable and powerful.

In the wake of this failure, the current Mexican government, led by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has de-escalated the conflict to focus more on policing and prosecution. Other Latin American leaders, across the political spectrum, want to call off the war on drugs altogether and begin advancing decriminalization and treating excess drug use as a social problem.

For now, calls to bomb Mexico are mostly primary-season bluster. But if a Republican were to win the White House in 2024, he or she would be under pressure to make good on the promise to launch military strikes on Mexico. Those efforts are not just bound to fail; they also could even make matters worse. Fentanyl labs are hardly complicated operations — with a couple of plastic drums and a pill press, one cook in a hazmat suit can turn out thousands of doses in a day. Trying to eliminate them with drones and missiles would be as effective as bombing bodegas in the Bronx. Hit one lab and five more pop up, perhaps in more populated areas.

Further militarizing Mexico’s drug war would lead to more corruption, more deaths, more refugees desperate to cross the border. And those displaced, if Republicans had their way and Mexican cartels were classified as terrorist organizations, would have a better shot at claiming asylum, since they would be fleeing a formally designated war zone.

With each escalation of the drug war, its horrors have inched closer to the United States. Now war mongering threatens to destroy the fragile movement among U.S. policymakers toward a more humane approach to drug use, that possession and use of drugs shouldn’t bring draconian prison sentences and that addiction should be treated as an illness, rooted in class inequality. Republican calls to go hard against narcotics below the border can’t but rebound above it, leading back to a callous public policy that treats addicts as enemies. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said of another war, the bombs we drop there explode here.

.

Greg Grandin (@GregGrandin) is a professor of history at Yale and the author of seven books, most recently, “The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America,” which won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction.

.