Florida, with its more laissez-faire approach, seemingly saw a less severe winter, prompting supporters to take something of a victory lap. But over the next year, as Florida officials adopted a more critical view of COVID-19 vaccines, the Sunshine State’s fortunes waned. The following summer’s surge, fueled by the Delta variant, was particularly deadly — despite vaccines being widely available.

by Rong-Gong Lin II, Luke Money, Sean Greene, LA Times

When California Gov. Gavin Newsom and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis take the stage Thursday for their much-hyped televised debate, it will be perhaps the starkest visual representation of the divide between the two states.

While many social, political and economic factors contribute to that gulf, perhaps no topic better encapsulates the bicoastal conflict than the states’ respective responses to the COVID-19 crisis — the ramifications of which are still resonating and being debated half a year after the end of the pandemic’s emergency phase.

On one side was California, which “trusted in science and data,” as Newsom has put it, and was “the first state to issue a stay-at-home order, which helped us avoid the early spikes in cases.” It was part of a strategy the Democratic governor reasoned was worth the sacrifice: “People are alive today because of the public health decisions we made.”

And on the other was Florida, whose approach DeSantis touted as mindful of economic health — attacking temporary business closures and vaccine mandates.

“We refused to let our state descend into some type of ‘Faucian’ dystopia, where people’s rights were curtailed and their livelihoods were destroyed,” the Republican governor said during a March speech at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, referencing Dr. Anthony Fauci, one of the architects of the nationwide COVID-19 response, who has since retired.

Though the controversy over stay-at-home orders and mask mandates preoccupied the minds of many early in the pandemic, the deeper, more lasting debate surrounding COVID vaccines may be the most notable distinction between the states.

By the first winter wave of the pandemic, COVID-19 rampaged through swaths of California, sending patients to the hospital in droves, overwhelming Los Angeles’ morgues with bodies and prompting officials to issue new stay-at-home orders.

Florida, with its more laissez-faire approach, seemingly saw a less severe winter, prompting supporters to take something of a victory lap.

But over the next year, as Florida officials adopted a more critical view of COVID-19 vaccines, the Sunshine State’s fortunes waned. The following summer’s surge, fueled by the Delta variant, was particularly deadly — despite vaccines being widely available.

Given how different California and Florida are — in terms of the age of their populations, overcrowded housing and the like — it’s hard to establish a definitive scorecard of who handled COVID-19 better in terms of policy. Structural factors may have provided one state an advantage at any point in time.

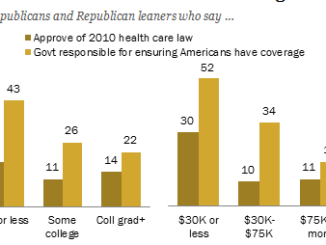

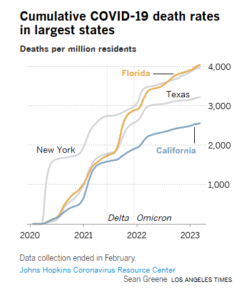

But in raw terms, significantly more Floridians died on a per capita basis during the COVID-19 emergency than Californians. Of the four most-populous states, California had the lowest cumulative COVID death rate: 2,560 for every 1 million residents. Florida’s rate was 60% worse, with 4,044 COVID fatalities for every 1 million residents, according to a Times analysis of Johns Hopkins University data through early March, when the university ended its data tracking.

In other words, Florida’s raw death tally — 86,850 in early March — came close to California’s total, 101,159, despite California having roughly 18 million more residents.

The overall death toll, however, may not tell the whole story.

The overall death toll, however, may not tell the whole story.

When factoring in demographics, another estimate has Florida with an age-adjusted COVID mortality rate that’s only slightly higher than California’s. And when adjusting for how Florida’s population is relatively unhealthier than California’s, another estimate actually ranks Florida better.

Such caveats cut both ways, though. The pandemic revealed just how rapidly COVID can carve through overcrowded settings. That proved to be a big vulnerability in California, particularly in Los Angeles County, where more homes are overcrowded than in any other large U.S. county, according to a Times analysis of census data published last year.

And Florida’s status as a state with one of the oldest populations in the country might have, counterintuitively, prevented the coronavirus from spreading as quickly in the pre-vaccine era. Many of Florida’s seniors may have strictly avoided gatherings during that first winter while younger, restriction-weary Californians could have been more apt to travel, socialize and potentially pass the virus to more vulnerable family members.

DeSantis’ message on COVID shots evolved from boasting about his state’s high vaccination rate among seniors in early 2021 to this year accusing federal agencies of using “healthy Floridians as guinea pigs.” He asserted that the latest inoculations “have not been proven to be safe or effective,” despite strong evidence cited by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Food and Drug Administration that they are.

Some health experts say Florida could’ve curbed its deadly 2021 summer surge had more younger adults gotten vaccinated and different mitigation policies been implemented.

By mid-June 2021, about 3 in 4 seniors in both Florida and California had completed their primary vaccination series. But just 43% of Florida’s younger adults had completed theirs, compared with 54% in California.

Earlier in the pandemic, only 20% of COVID-19 deaths in Florida were people younger than 65. But that share climbed to 40% during the peak of the Delta wave, according to Jason Salemi, associate professor of epidemiology at the University of South Florida.

“That was an astonishing number,” he said.

The lower vaccine uptake in younger adults probably played a role.

“It didn’t need to be as bad as it was — because I felt like if we would have all kind of read the tea leaves and seen what was happening and started to … do [more] mitigation efforts … I think it would have resulted in a much lower morbidity and mortality rate during the Delta wave,” he said.

As documented by Florida journalists, DeSantis changed his tone on COVID vaccines by spring 2021 and since has elevated voices skeptical of them.

Florida had an enviable early-vaccination rate among its seniors. But when it came to boosters — which first became available in fall 2021 — the state had one of the nation’s worst coverage rates for older adults by the end of the pandemic emergency in spring 2023.

By early 2022, as the highly infectious Omicron variant spawned what eventually would prove the second-deadliest surge of the pandemic nationally, 69% of California’s seniors had received their first booster, compared with 59% of Florida’s seniors, according to data from the CDC.

As of early May, 48% of California’s seniors had received an updated booster formulated specifically to combat Omicron, compared with 31% of Florida’s seniors.

Since DeSantis’ shift on vaccines, Florida’s cumulative COVID death rate began climbing at a faster pace than California’s — a pattern that continued through the end of the pandemic emergency in May.

That shift accelerated after DeSantis appointed a new health secretary and surgeon general, Dr. Joseph Ladapo, who has issued a number of recommendations and statements that have been roundly criticized by other medical officials and experts.

The CDC and FDA went so far as to write an extraordinary public letter rebuking some of Ladapo’s claims — such as his recommendation that young men not receive mRNA vaccines because of an increased risk of cardiac complications. The CDC and FDA said the assertion was “incorrect, misleading and could be harmful to the American public” and said the risk of stroke and heart attack are actually lower in vaccinated people, not higher.

Ladapo reiterated his critical stance on the latest COVID-19 vaccine formulation in September, and recommended against the shots for those younger than 65. That defied official federal recommendations, which called for virtually everyone 6 months and older to get an updated vaccination this autumn.

COVID-19 continues to pose a “risk at all age groups,” CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen said in an interview with the “In the Bubble with Andy Slavitt” podcast when asked about Florida’s recommendations. “We also see a very safe vaccine.”

California health officials have defended their approach to the pandemic as appropriately rooted in science, and ultimately effective.

“Do I think California did better than Florida? I think your crude numbers show that we did,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s health and human services secretary.

But, he added, “Do I think if you really got small and granular, whether it’s age adjustment, or other adjustments, and add layers of comorbidity … can you split this even further? Absolutely.

“I guess the question for me is: What does it tell you?” he said. “And in California, I think the data does speak for itself.”

California and Florida had similar cumulative COVID-19 death rates in the first few months of the pandemic. But Florida’s rate accelerated faster starting in summer 2020 as the state more quickly loosened restrictions.

California saw its own cumulative death rate rise at a faster pace than Florida’s during the first pandemic winter, and the gap between the two states narrowed. Still, for virtually the entire pandemic, California’s cumulative death rate has remained below Florida’s.

A Times analysis of the unadjusted COVID mortality rate, based on the Johns Hopkins University tally, shows that Florida had the highest rate of the four most populous states — and the 12th-worst of the 50 states. California’s rate was 11th lowest of all states.

A separate calculation, which adjusts for age in a database run by the CDC, had Florida with a slightly worse ranking than California — the 34th highest age-adjusted COVID mortality rate versus the 38th highest.

A third analysis, published in the medical journal the Lancet earlier this year, looked at COVID-19 death rates through the end of July 2022 and calculated Florida as having a 43% worse unadjusted death rate than California. But when adjusted for differences in age, the gap was narrower — with a 12% worse death rate in Florida. When also factoring in how Florida’s population as a whole is unhealthier than California, in addition to the age adjustment, the roles reversed and California had a 34% worse adjusted death rate.

But California and Florida may be outliers. A broader look at data from the Lancet report show that states in the South, Southwest and Rocky Mountains had a worse COVID death rate, even when adjusted for age and health conditions, compared with the Northeast and Pacific Northwest.

“Our results suggest that vaccine coverage is linked to fewer COVID-19 deaths, and protective mandates and behaviors were associated with fewer infections,” the Lancet analysis said. “The states that implemented and maintained more mandates were statistically associated, on average, with higher mask use and greater vaccine coverage rates, which in turn were associated with fewer infections.”

Generally, the Lancet analysis found that poverty, lower educational attainment, higher rates of chronic health conditions, limited access to quality healthcare services and lower rates of “interpersonal trust” — trust that people have in one another — were statistically associated with worse COVID-19 mortality rates.

Some experts are wary about comparing death rates, given how vastly different states can be. Any state-level analysis may also paper over regional differences — L.A. County’s death rate, for instance, was much higher than the San Francisco Bay Area’s.

The University of South Florida’s Salemi called such comparisons “apples and oranges.”

“There’s so many factors at play that help a county or state navigate a pandemic. … It’s not just about these policies, it’s not just about vaccination uptake — although all of those things certainly matter. It’s just such a challenging thing to isolate the independent effect of each,” Salemi said.

In terms of overall judgment of policymakers in how they tried to tackle the COVID crisis, Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the Department of Medicine at UC San Francisco, said he thought California was following the scientific evidence “better than many other states, including Florida.”

“When you looked at the early curves of death rates, it was substantially lower in California than in many other states. I think a lot of lives were saved at that stage,” he said.

There’s lately been a lot of hindsight history, with some questioning whether the tough measures early in the pandemic were an overreaction, Wachter said. But generally, he said, “I don’t know how you say that when you have well over a million Americans that have died.”

Had Florida been in a vaccine-skeptical mood earlier, “there would be many, many, many more deaths in Florida,” Wachter said. “So I’m grateful that — in part because my mother lives there, and she’s older — that the early message at least was in keeping with what the science tells us to do.”

Rong-Gong Lin II is a Metro reporter based in San Francisco who specializes in covering statewide earthquake safety issues and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Bay Area native is a graduate of UC Berkeley and started at the Los Angeles Times in 2004.

Luke Money is an assistant editor on the Fast Break Desk, the Los Angeles Times’ breaking news team. He joined the newsroom as a reporter in 2020, specializing in breaking news and coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. He previously was a reporter and assistant city editor for the Daily Pilot and before that covered education, politics and government for the Santa Clarita Valley Signal. He earned his bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Arizona.

Sean Greene is an assistant data and graphics editor, focused on visual storytelling at the Los Angeles Times.