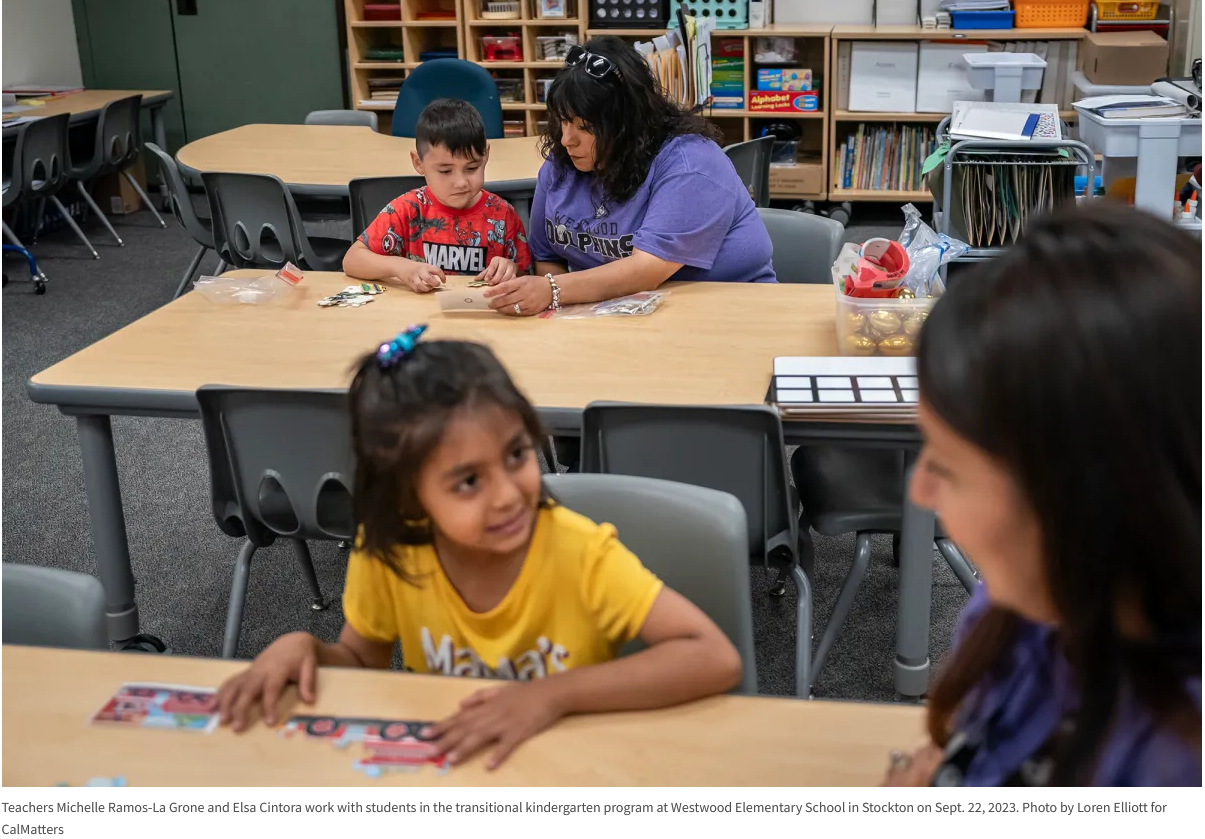

California is rolling out its transitional kindergarten program, with the goal of offering it for all 4-year-olds by 2025-26. While some schools have had programs in place for years, others are just starting to create teaching guidelines.

, CalMatters

Thanks to TikTok videos, billboards and other creative marketing techniques, enrollment in transitional kindergarten in California appears to be climbing. But advocates are keeping an eye on how those 4-year-olds are spending their class time — which they say will be a key factor in whether the $2.7 billion program is a success.

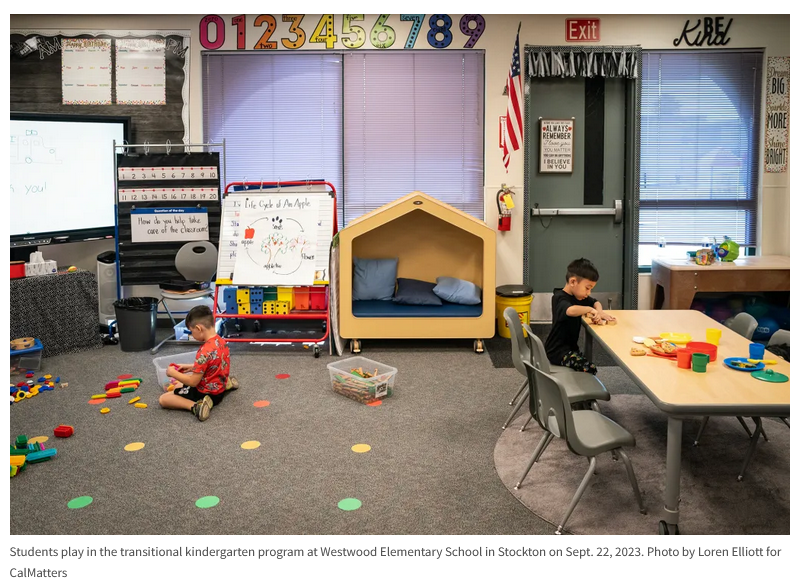

“Quality is top of mind for us. Some districts are treating it like a second year of kindergarten, which we know doesn’t work,” said Benjamin Cottingham, with Policy Analysis for California Education, an independent, nonpartisan research center. “To be effective, TK needs to be a play-based, developmentally appropriate course of study.”

Transitional kindergarten, which California first launched in limited capacity in 2010, is meant to ease 4-year-olds into the rigors of elementary school. Ideally, it combines the carefree fun of preschool with a hint of structure and academic know-how, so children are better prepared for kindergarten and beyond. In a high-quality TK classroom, children learn to share and take turns, draw pictures and play with blocks, sit in a circle and enjoy story time, among other skills.

A study of California’s TK program by the American Institute of Research found that children who completed TK had stronger skills in math and literacy when they started kindergarten and were more engaged in learning than their peers who didn’t participate in the program. The benefits were especially pronounced for English learners and low-income students.

In 2021, California expanded its transitional kindergarten, requiring schools to provide space for all eligible 4-year-olds whose families want it. With a rollout period of five years, schools have been busy hiring and training teachers, buying more crayons and blocks, converting classrooms to meet state guidelines and getting the word out.

After a lull, enrollment appears to rebound

In 2022-23, enrollment lagged below expectations, likely due to the lingering effects of the COVID pandemic, according to the Legislative Analysist’s Office. Just over half of California’s eligible 4-year-olds were enrolled in TK last year, roughly 22% below state projections. But now enrollment appears to be increasing. The official numbers for 2023-24 won’t be available for several months, but a CalMatters sampling of districts statewide reported better-than-expected enrollment so far this year.

Schools credit the uptick to improved outreach. District staff are talking to parents at local preschools and child care centers, posting flyers in pediatricians’ offices, buying ads on social media and even going door-to-door.

In Rescue Union School District in the Sierra foothills of El Dorado County, word-of-mouth has been the most effective recruitment tool, said Superintendent Jim Shoemake. The district bought newspaper ads and put up signs, but nothing compares to the power of parents chatting at barbecues, block parties and soccer games. Enrollment has increased steadily, with 142 students enrolled this year, and the retention rate is nearly 100%, he said.

“TK has benefitted the entire district,” Shoemake said. “It’s great to have a child on campus for six years, but seven is even better. We get a chance to onboard these kids early, so they’re successful not just in elementary school, but middle school and beyond.”

Rescue Union parent Aly Perkins said her twin daughters, Hazel and Scarlett, loved their TK class last year. They learned their ABCs and 123s, but it was social skills that had the biggest impact, she said.

“They learned things like manners, how to make friends, how to keep friends — those skills will benefit them their whole lives,” Perkins said. “I think TK gives kids the confidence and cushion they need to succeed in school. I’m really glad we decided to send them.”

Even in Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, word-of-mouth has been key to TK enrollment. In addition to bus ads and billboards, a social media campaign, a hotline and robocalls, the district has enlisted school staff and parent volunteers to hand out flyers within a four-block radius of elementary schools.

“A parent saying, ‘I have my kid in this program and it’s great’ is much better than it coming from me,” said Dean Tagawa, the district’s executive director for early childhood education. “That parent-to-parent connection, that level of trust, is what’s important.”

“We get a chance to onboard these kids early, so they’re successful not just in elementary school, but middle school and beyond.”

Jim Shoemake, superintendent of the Rescue Union School District

The tactics seem to be working. Los Angeles Unified has opened TK classrooms at nearly all 488 elementary schools. And children who attended the district’s TK program have significantly outperformed their peers not in the program in reading, writing and math in kindergarten and first grade, according to district data. They also fared better social-emotionally, based on teacher feedback on report cards.

In Lodi Unified, a TikTok video chronicling a day in the life of a Lodi kindergartener has garnered more than 13,200 views and helped fill classrooms. With enrollment exceeding expectations, the district is on track to open at least one TK classroom at every elementary school by 2025-26.

“Overall, it’s going really well, and I believe that by the time these students are in third grade, we’re going to see huge improvements in outcomes,” said Susan Petersen, the district’s director of education.

Persistent staffing challenges

While some districts have struggled to hire enough TK teachers, Lodi Unified has filled all its vacancies, she said. The district is providing training and in-classroom coaching, and using a curriculum focused on learning through playing. Some of the new TK teachers are credentialed elementary teachers, and some are veteran preschool teachers pursuing credentials.

“We’ve found that it’s a sought-after position,” she said.

Recognizing that 4-year-olds learn in unique ways, the Legislature will require by 2025 TK teachers to have credentials as well as 24 units of early childhood education or the equivalent. That extra requirement may pose a barrier to filling positions — many districts are already grappling with teacher shortages. An analysis by the Learning Policy Institute last fall found that 80% of school districts in California didn’t yet have enough qualified TK teachers.

Meanwhile, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing is working on a new credential that will prepare teachers for preschool through third grade, with a focus on literacy. A goal: create a seamless continuum in which students learn by playing, rather than sitting at desks.

That focus on high-quality teaching and learning is imperative if TK is going to succeed in getting students ahead in the early years, Cottingham said. The state is updating its preschool guidelines to include TK, but schools cannot afford to wait for the new version; they should “work with what we’ve already got,” or students will lose out on the benefits of an additional year of schooling, Cottingham said.

Assessments will also be important, he said, to hold districts accountable for the quality of their programs. Currently, the state is not requiring schools to test students in TK, although it does provide guidelines on how to measure students’ progress.

Hanna Melnick, senior policy adviser at the Learning Policy Institute who co-leads the early childhood learning team, adds that assessment, as well as curriculum, will be important as TK expands.

“The TK rollout has been faster than we expected, but we don’t have a good way to monitor quality, and district capacities to teach 4-year-olds vary greatly,” she said. “Some have been doing this for a long time, and some are new and don’t yet have the background or training.”

‘A system that’s working’ in Tulare

Tulare City School District, a 9,200-student district south of Fresno, has been offering a cohesive preschool-through-first-grade program for a decade, and seeing positive results. Until the pandemic, third grade math and reading scores had jumped nearly 30% since the district implemented the program in the early 2010s. Now they are again beginning to improve.

The curriculum is linked from grade to grade, and teachers work closely together, easing children’s transitions from one classroom to the next. All sites offer after-school care, making it easier for parents with jobs. And teachers try to get to know families and ensure they feel welcome and part of their children’s education, said Jennifer Marroquin, the district’s assistant superintendent of educational services.

“For parents, it can be scary dropping your 3- or 4-year-old off for the first time. So we try to make them feel supported,” Marroquin said. “We found a system that’s working, and it’s become one of our district’s strengths.”

By the time TK is fully in place statewide, most districts should have programs resembling Tulare’s, said Kelly Reynolds, a policy analyst for Early Edge California, a nonprofit advocacy group that’s worked closely with the state on transitional kindergarten. She expects the challenges with staffing, enrollment and quality will be resolved — or close to it — within the next few years.

Because transitional kindergarten, like kindergarten itself, is not mandatory, enrollment will never be 100%, she noted. And depending on where they live, 4-year-olds have plenty of high-quality options aside from TK — including private preschool, state-supported preschool, child care and Head Start.

“We want to make sure all 4-year-olds are being served in high-quality programs, and families know the breadth of opportunities available to them,” she said. “I do think we’re on track. Enrollment is trending upwards, and we’re seeing there’s a real demand for TK.”

.

Carolyn Jones covers K-12 education for CalMatters. Previously, she worked at EdSource, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Oakland Tribune. She recently served as a Fulbright Specialist in Albania focusing on media literacy. A graduate of UC Berkeley, she’s a longtime Oakland resident.