In the last half-century, working-class suburbs across Southern California have undergone a similar demographic and cultural shift. In Los Angeles County, roughly half the population self-identified as Hispanic on the 2020 census.

Stepping through the ornate facade of a faux City Hall, I enter the indoor swap meet at Plaza Mexico, the kitschy shopping center that’s a landmark of California’s resurgent Latino identity. I’m in the town of Lynwood, but the vibe is nothing like the WASPy Los Angeles of my 1970s youth. At the traffic circle that serves as the Plaza’s entrance, I find a copy of the Angel of Independence, a famous monument in Mexico City that commemorates the beginning of Mexico’s fight for secession from Spain. The replica Mexican municipal building, or ayuntamiento, features the eagle and the serpent of Mexico’s coat of arms. This building was, in another time, a Montgomery Ward department store. Now I walk through it and enter the Latino equivalent of Disneyland.

Plaza Mexico is a phantasmagoric translation of a Mexican village, where vendors have created an aesthetic that Latino art critics call rasquachismo, meaning improvised and unpolished. During my visit, I see one store offering a garden fountain featuring a tiny Jesus inside an old washtub painted cerulean, and what appear to be four bronze bowling pins hovering like spaceships around him; it goes for $320. Asian women staff a nail salon bathed in bright fluorescent light. A food stand offers tamales, chimichangas and an exotic delicacy made with fresh corn — elotes con Hot Cheetos. Call it Mexicoland: a new kind of “Latinidad” that’s working class and distinctly Californian, grounded in the state’s diversity and our faith in an increasingly elusive American dream. If “Latino” is already a kind of synonym for “mixed,” in California this mixing has become ever more complex.

A few decades ago, this resurgence of Latino culture would have seemed unlikely. In the 1960s, the future locale of the Plaza Mexico was known as “lily-white Lynwood.” The locals drank vanilla Cokes at a drugstore soda fountain downtown, and department stores catered to a blue-collar white clientele. A Los Angeles Times reporter would later remember it as a time of “boosterism, Boy Scouts and high hopes.” These halcyon days shined only for some, though. In the popular American imagination of that time, Latino identity was often equated with service, manual labor and servility. This lingers today, as Latino immigrants are routinely denigrated in the media, their homelands equated with barbarism and poverty.

By 2020, though, Lynwood was nearly 90 percent Hispanic. In the last half-century, working-class suburbs across Southern California have undergone a similar demographic and cultural shift. In Los Angeles County, roughly half the population self-identified as Hispanic on the 2020 census. Immigration from Latin America has transformed life in the Golden State in countless ways, from our food habits to our amorous entanglements. Whether at their workplaces or in their neighborhoods, many non-Latino Californians live in daily contact with Latinos. Cultural significance is often prelude to political power. A generation after Californians voted for ballot measures that limited Spanish instruction in schools and banned undocumented immigrants from public services, Latino leaders are now active in most levels of state government. In Sacramento, Latino legislators have helped approve laws granting driver’s licenses and in-state college tuition to the undocumented. In Lynwood, there are Latino majorities on the City Council and school board.

Here, these changes have been driven, in part, by California’s cycles of boom and bust, and the growing economic and racial disparities that accompany them. When the California Department of Transportation purchased huge swaths of real estate in the 1970s to build Interstate 105 — the freeway that would link the newly developed suburbs of south Los Angeles County — Lynwood was cut in half, and property values plummeted. Middle-class Black families moved into Lynwood as white families moved out, and “lily-white Lynwood” began to collapse. The Montgomery Ward shut down. Lynwood and neighboring Compton became Latino barrios as crises in Mexico and Central America sent large numbers of immigrants northward. Meanwhile, two Korean brothers, the Chaes, purchased the old Montgomery Ward building and transformed it into an indoor swap meet catering to a mostly Latino clientele.

Here, these changes have been driven, in part, by California’s cycles of boom and bust, and the growing economic and racial disparities that accompany them. When the California Department of Transportation purchased huge swaths of real estate in the 1970s to build Interstate 105 — the freeway that would link the newly developed suburbs of south Los Angeles County — Lynwood was cut in half, and property values plummeted. Middle-class Black families moved into Lynwood as white families moved out, and “lily-white Lynwood” began to collapse. The Montgomery Ward shut down. Lynwood and neighboring Compton became Latino barrios as crises in Mexico and Central America sent large numbers of immigrants northward. Meanwhile, two Korean brothers, the Chaes, purchased the old Montgomery Ward building and transformed it into an indoor swap meet catering to a mostly Latino clientele.

Give the Latino families in Lynwood a taste of the old country, the thinking went, and maybe they’ll spend a little of their hard-earned cash, too. To create his marketplace, Hidalgo returned to Mexico several times and met with old relatives, including a great-uncle who was a general in the army. Above all, he played tourist. “What is the essence of this culture?” Hidalgo asked himself as he walked through old colonial cities and archaeological sites, including Chichén Itzá in Yucatán. “I brought all these elements into the melting pot of my brain,” he says.

At Plaza Mexico, the Latino community has accepted the invitation to celebrate their culture. In the open-air mall, I see homeboys taking selfies in front of a fountain of concrete feathered serpents, replicas of the ancient stone sculptures found at Teotihuacán. I find installations erected by Mexican states after the shopping center opened in 2004, including a statue of Pancho Villa and a reproduction of the iconic Aztec Sun Stone.

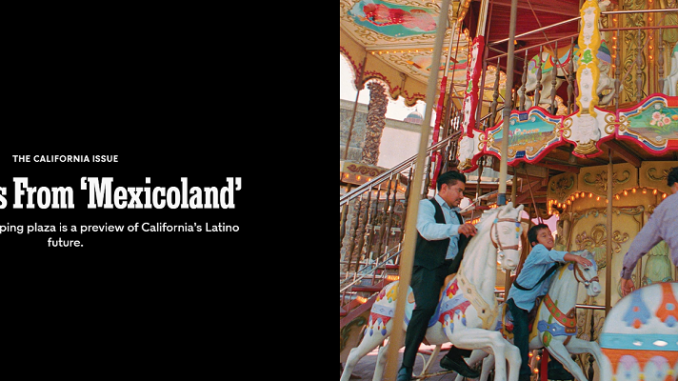

A stroll through the shopping center reminds you that Latin American culture can be monumental, beautiful and heroic. Here, Latino people reimagine themselves inside the Mexican and Central American villages of family lore, territories now separated from them by increasingly policed borders. When school lets out in the afternoons, the vendor Alvaro García watches as parents take their children to the old-fashioned merry-go-round next to his outdoor artesanía, or handicrafts, stand. García, 64, told me that he and his brother have operated their stand at Plaza Mexico for a dozen years. Zapotec is his first language; Spanish his second. He first migrated to the United States in 1995 and worked in the tomato harvest, then in a Chinese restaurant, before finally starting his own business. Most of what García sells are textiles imported from his native Oaxaca. Somehow, his Plaza Mexico stand survived the pandemic.

But not everyone made it through the hard times. “I know 10 families that have moved backed to Oaxaca,” he says. “Entire families.” When I ask him if he still thinks of California as the land of opportunity, he answers in Spanish: “Se acabó.” Meaning, that’s over. People in Mexico don’t realize how tough things are in California, he adds. Lynwood is a town where three-bedroom homes can go for more than $600,000. García says he tries to disabuse his Mexican relatives of the notion that California is Easy Street. “We sleep on the floor,” he tells them. “Luxuries, cabrón: There aren’t any here.”

Boosters have long portrayed California as a utopia where people can reinvent and enrich themselves. In some ways, Plaza Mexico is a Latino version of that story, told by those who were long excluded from what the state has to offer. Here, I’ve seen how a new, American way of being “Latino” is being assembled from contact with many different cultures. For example, the architectural historian Alec Stewart has noted that the many Southern California indoor swap meets were built, like Plaza Mexico, by Korean entrepreneurs to serve a predominantly Latino and Black clientele, and bear a strong resemblance to the textile markets of Seoul. These Asian-run businesses might hire folklórico dancers and mariachis to lure in a working-class clientele.

Like the individual architectural styles that Plaza Mexico incorporates, the old race and ethnic labels (Black, white, Hispanic, Asian) don’t quite capture the drama of cultural intermingling we see on the ground. California is outracing all of that; its polyglot present foreshadows the nation we are becoming.

.

Héctor Tobar is a Los Angeles-born author of six books, including, most recently, “Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of ‘Latino.’” Deb Leal is an artist, director and photographer currently based in Brooklyn and Oakland, Calif. Her work explores time and memory through color and composition.