Mexico is a very different country than it was before the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, with its GDP rising from $261 billion in 1990 to $1.27 trillion in 2020.

by Daniel F. Runde, Linnea Sandin, andIsaac Parham, CSIS

Introduction

The next four years present a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the new Biden administration to engage with Mexico and with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) to reinforce the trade relationship between the two countries. The recent entering into force of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), global disruption due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and administration changes on both sides of the border present a unique combination of circumstances that should be seized upon throughout the next four years.

AMLO came into office in 2018 under the auspices of a populist campaign, promising to address endemic poverty and expand development in the country. With a 62 percent approval rating, AMLO has more popular support than any other major leader in the Americas, including Joe Biden, Jair Bolsonaro, and Justin Trudeau. He has the massive popular support necessary to enact sweeping reforms, with plans to reclaim Mexico’s oil industry under state-owned enterprises and to train a modern workforce through educational programs.

Mexico is a very different country than it was before the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, with its GDP rising from $261 billion in 1990 to $1.27 trillion in 2020, making it the second largest economy in Latin America after Brazil. This phenomenal growth can be largely attributed to a strong relationship with the United States since the implementation of NAFTA. In 1990, bilateral trade between the United States and Mexico stood at just $38.3 billion, and Mexico was the United States’ third-largest trading partner. By 2019, the trade volume reached $614.5 billion, and Mexico became the United States’ largest trading partner for the first time that year.

AMLO . . . has the massive popular support necessary to enact sweeping reforms, with plans to reclaim Mexico’s oil industry under state-owned enterprises and to train a modern workforce through educational programs.

Trade, development, and investment are entwined with the issues of regional security and migration that will continue to be priorities for the Biden administration. AMLO recently appointed a new economic minister and a new deputy governor of the Central Bank, roles which traditionally advise the president on economic policy. The new appointees are anticipated to engage in more open dialogue with the private sector compared to their predecessors, and they could be key to the full implementation of the USMCA over the next four years if they can more effectively persuade AMLO. In the context of a global pandemic, a novel and open-minded cabinet, and a growing bilateral trade volume, there is no better time for the Biden administration to advance a revamped trade and investment agenda in Latin America. This historic, tumultuous moment represents a unique window of opportunity for the United States and Mexico to work together through the USMCA to not only promote their own economic recovery, but to prepare for the future in a way that will make the entire North American market competitive for years to come.

Trade, development, and investment are entwined with the issues of regional security and migration that will continue to be priorities for the Biden administration.

NAFTA and the USMCA

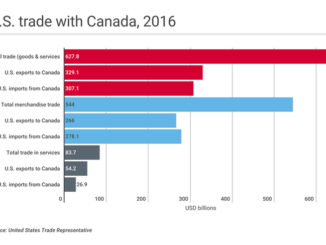

Trade is traditionally one of the most prominent topics of dialogue and policy between the United States and Mexico. NAFTA was hailed as a generational policy achievement, and for good reason: trade among the three member states ballooned from around $290 billion in 1993 to over $1.1 trillion in 2016, representing nearly a third of global GDP and solidifying the interdependence of the North American economies. Mexico benefited from the agreement, increasing exports to the United States tenfold from $39.9 billion in 1993 to $358.1 billion in 2019. The trade relationship between NAFTA members has also ensured general goodwill and friendly diplomatic relations over the past two decades. NAFTA was a groundbreaking accord that helped launch what was once the world’s largest free trade agreement, representing approximately 33 percent of the world’s total gross domestic product and the second largest in total trade volume.

A substantial component of U.S.-Mexico trade expansion through NAFTA has involved the creation of vertical supply chains, which strengthened the competitiveness of U.S. companies and helped Mexico accelerate its diversification of exports and imports. Vertical specialization was used in manufacturing production maquiladoras (Mexico’s export-oriented assembly plants) across the U.S.-Mexico border: maquiladoras use large amounts of imported materials produced in the United States and assemble them into the final product, and then export most of the final product back to the United States with duty-free status. Vertical specialization has allowed the United States and Mexico to leverage their economies by collaborating in the manufacturing and assembly of various products, including automobiles, computers, and electronics. Mexico is now one of the largest auto manufacturers in the world, producing almost 4 million cars per year.

Due to the process of vertical specialization and overall growth in trade, NAFTA and the subsequent USMCA have set North America up to become a unitary market with the potential to compete globally. Making the most of this vertical supply chain will be essential, given the context of China’s growing influence throughout the world, and especially in Latin America and the Caribbean. Nearshoring production and implementing the various reforms of the USMCA would not only strengthen the economic and diplomatic ties between the three member states but also make the North American regional supply chain an attractive alternative to competitors like China and the European Union.

This historic, tumultuous moment represents a unique window of opportunity for the United States and Mexico to work together through the USMCA to not only promote their own economic recovery, but to prepare for the future in a way that will make the entire North American market competitive for years to come.

Changes to USMCA That Allow Regionalization

Political forces on both sides of aisle in the United States have been pushing for updates to NAFTA for years. Former president Trump made updating the agreement a central promise of his 2016 campaign, and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement ultimately passed the U.S. Senate by a vote of 89-10. The amended agreement retained much of the structure of the previous NAFTA, but included several key changes, such as:

- Enhancing the dispute settlement process;

- Providing more enforceable labor provisions and requirements for Mexico to reform its labor laws and practices, such as mitigating forced labor and violence against workers;

- Expanding coverage, enforcement, and monitoring of environmental protections;

- Tightening vehicle rules of origin by establishing a 75 percent regional value content requirement for finished vehicles and a similar rule for automobile parts to meet the criteria for zero tariffs for automobiles;

- Requiring that 40–45 percent of auto content be produced by workers making at least $16 per hour;

- Incorporating new trading provisions and protections related to the digital economy;

- Amending some of the patent and regulatory exclusivity provisions, especially related to the pharmaceutical industry; and

- Establishing a “sunset clause” for the duration of the agreement term, leaving it open to a review every six years.

In particular, the dispute resolution mechanism and sunset clause amendments should be recognized for their potential to drive a new era of North American relations. As the Biden and AMLO administrations strive for leverage throughout the process of USMCA implementation, they will inevitably clash. For instance, the administrations have different trajectories with regards to environmental regulation, and they will likely need to address the United States’ $101 billion trade deficit with Mexico. While conflicting interests would typically impede implementation, the goal of the dispute resolution mechanism is to provide a legal framework for considering varying perspectives and avoiding runaway taxation. If dispute resolution falls through, the six-year periodic review acts as a safeguard, allowing parties to make a case for their entrenched positions at that time.

Sectors for Potential Collaboration

Energy

The energy sector is one of both growing importance and consistent dispute between U.S. and Mexican administrations, and it will be a frontier of negotiation in the coming years. Mexico is the second-largest supplier of crude oil to the United States and the largest export destination for U.S. natural gas and petroleum products. AMLO campaigned heavily on the concept of “energy sovereignty,” with the goal of reining in state-run energy companies—such as Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE)—and reinvigorating their production. The oil industry in Mexico is not only a source of employment, but is celebrated as a shared commodity that is worthy of national pride by the citizenry, leading AMLO to campaign strongly on the issue. By contrast, President Biden campaigned on increasing environmental accountability and rejoined the Paris Climate Accord on his first day in office. His environmental platform includes plans for the United States to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, create a new sector of renewable energy jobs, and work with multilaterals to address the threat of climate change.

Over the last two years, AMLO has added obstacles to environmental accountability, such as regulatory bureaucratic changes, including disincentivizing foreign investment in more than 200 energy projects. The Mexican economic ministry also directly opposed the integration of privately-owned wind and solar plants into the national power grid in a move to protect CFE. Consequently, the business climate environment in the energy sector had declined by more than half, from $2.25 billion in 2019 to approximately $1.3 billion in 2020. 23 percent of Mexico’s energy comes from renewable sources, and it is among the top 10 destinations for renewable investment in the world. However, due partly to the previously mentioned patriotic attitude towards oil and gas and a desire to help Pemex, AMLO has discontinued clean energy auctions that had previously introduced 7 gigawatts of wind and solar power to Mexico. AMLO has shown no signs of abating this behavior; on February 5 he sent an electricity reform bill to the Mexican Congress that was immediately called out as a breach of USMCA by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

President Trump and AMLO had a somewhat comfortable trade relationship, as Trump focused mostly on migration during his tenure, allowing AMLO to continue his energy policies. Biden is expected to focus significantly more on the environment, which could be done through full implementation of the USMCA. Environmental provisions under the USMCA include obligations to multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) by the parties, as well as the U.S.-Mexico Environment Cooperation and Customs Verification Agreement. Perhaps more influential are the USMCA Investment Provisions, meant to guarantee the free flow of foreign direct investment in North America and to restore investor trust and transparency. AMLO’s protectionist energy policies—and particularly his proposal to overturn a 2014 constitutional amendment that expanded private investment opportunities—would violate the USMCA.

Manufacturing

The trade of motor vehicles and machinery between the United States and Mexico is one of the most, if not the most, influential sectors of the trade relationship. Automotive and manufacturing trade represents the largest volume of Mexican exports to the United States, totaling $231 billion between vehicles and machinery in 2019 out of a total export market of $358.1 billion that same year. While U.S. exports of machinery and automobiles to Mexico are not nearly as high in volume as imports, that export market still measured an impressive $107 billion in 2019 and represented a larger share of trade than other sectors, such as agriculture and services.

Manufacturing regulations and automotive trade were a major source of controversy under NAFTA, and they ultimately became a driving force for the Trump administration to update the agreement with the USMCA. U.S. auto manufacturing jobs fell by a third between 1994 and 2013, while the Mexican auto workforce grew by hundreds of thousands in the same period. The U.S. job decline was in fact attributable to a number of factors, including hundreds of thousands of jobs lost to automation and China’s designation as a most favored nation in 2001. However, the popular idea that manufacturers were moving to the cheaper Mexican labor market gained enough political momentum to effect bipartisan support for the USMCA in 2019. On the other hand, while AMLO had long derided free trade policies as harmful to the Mexican working class, he promptly welcomed the USMCA in hopes of improving Mexico’s stagnant poverty rate. The tightening of manufacturing and labor restrictions under the updated agreement signified that both governments were unhappy with the status quo, but the challenge ahead lies in its implementation.

As the Biden and AMLO administrations coordinate in the manufacturing sector, the most important applications of the USMCA will be in job creation. The provision increasing the required automotive regional value content to 75 percent could be leveraged to reinvigorate maquiladora production, and it is projected to create hundreds of thousands of jobs in the United States. Working together to address Covid-19 will also be an essential part of the manufacturing agenda, since the industry was one of the sectors most vulnerable to the pandemic. Factories in both countries took a blow at the beginning of the pandemic due to mandatory shutdowns and continue to struggle in enforcing safety measures months after reopening.

Pharmaceuticals

The pharmaceutical sector is an often-overlooked part of the regional North American relationship that has enormous potential for growth. The Covid-19 pandemic exposed a lack of public health preparedness in both the United States and Mexico, particularly in terms of personal protective equipment (PPE) stockpiles. The United States was already heavily reliant on globally sourced PPE prior to the pandemic, due to years of inadequate budgeting and prioritization in hospitals; at the same time, Mexico was slow to react to the drastic spike in PPE demand in its own borders.

As global demand for PPE and Covid-19 tests skyrocketed, many countries turned to China for help. China produced more PPE and respirators than the rest of the world combined long before Covid-19, but the demand of the pandemic expanded Chinese mask production by 1,200 percent in February 2020 alone. China’s supply of PPE was not altruistic, as the regime often engaged in “donation diplomacy” by requiring recipients of aid to publicly thank the PRC for shipments as a publicity tool. As the United States and Mexico failed to meet the needs of even their own citizens, they missed out on a valuable opportunity to provide an alternative to the Chinese market.

While the opportunity to become a go-to site for PPE exports has passed, the United States and Mexico have the potential to work together under the USMCA to prepare themselves and the world for the next public health crisis. One provision that represents an opportunity for growth in this sector is an intellectual property (IP) protection reform that will allow leaders to negotiate a decrease in the period of regulatory exclusivity for biotechnology patents. A more liberal flow of ideas and information in the realm of pharmaceuticals would allow the best minds in North America to collaborate and lead the world on the cutting edge of medical innovation.

Agriculture

Agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico is a significant sector of each country’s export markets that will need to be preserved and strengthened under the Biden administration. The United States is Mexico’s single largest agricultural trading partner, purchasing 78 percent of Mexican agricultural exports. Likewise, U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico totaled $19.2 billion in 2019, growing 48 percent over the last decade. The phenomenal growth of agricultural trade between the two countries is due to several reforms by the Mexican government over the past 30 years and to the country’s accession to multilateral organizations, but it is of course mostly attributed to the signing of NAFTA in 1994. Between 1993 and 2018, U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico grew at an annual rate of 6.9 percent, making it one of the most consistent and reliable U.S. export markets.

Many USMCA amendments have specifically targeted agriculture, with the overarching goal of increasing access to the U.S. agricultural export market and appeasing frustrated U.S. farmers. Key updates include the termination of discriminatory wheat and dairy grading systems and increased cooperation on biotechnologies—protectionist policies which led to widespread disdain with NAFTA and caused farm workers to push for an update. The expanded access to U.S. wheat, dairy, and textiles, as well as the newly established Working Group for Cooperation on Agricultural Biotechnology, carry major potential for improving this sector. In addition to an expected increase of $2 billion annually in U.S. agricultural exports, the transparency and information-sharing provided by the Working Group may ease Mexico’s historical apprehension toward genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and allow for regional production of more resilient crops.

Despite the laudable achievements of the USMCA in agriculture, some trade tensions in the sector have emerged on both sides of the border in the first year of implementation. The AMLO administration has pursued certain divisive food and agriculture policies, such as disparaging U.S. exports of corn sweeteners, and banning the use of glyphosate and GMO corn. The Trump administration, meanwhile, pursued complaints of unfair imports on seasonal produce from Mexico, launching multiple investigations covering an estimated 44 percent of U.S. seasonal produce imports from Mexico. Resolution of such nascent disputes will be a challenge for the Biden and AMLO administrations.

Tourism

The tourism corridor between the United States and Mexico is one of the most highly frequented in the world and is an essential sector of each country’s economy. Mexico is the most popular destination for U.S. tourists, attracting 26 million U.S. visitors in 2019, more than the European Union and Canada combined. While the volume of Mexicans traveling to the United States was slightly less at 18.1 million, Mexico is second only to Canada as a country of origin for international visitors to the United States. The tourism sector constitutes 8.5 percent of Mexican GDP and a massive 77.2 percent of service exports, and it was identified as a priority economic sector in the National Development Plan of 2013–2018. Tourism consistently outperforms other major economic sectors as a share of GDP, including auto manufacturing (3.7 percent), agriculture (3.6 percent), and oil and gas (2.2 percent). Similarly, travel is the United States’ second largest export and has major growth potential under the USMCA.

The tourism industry was obviously one of the hardest hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, as lockdowns and border closures ground international flights to a halt. International tourism was down 80 percent globally in 2020, and domestic tourism came nowhere close to making up for lost revenues; North America was no exception. As countries everywhere reimagine what the tourism will look like post-pandemic, the United States and Mexico should promote open dialogue and come to a shared vision on the issue. In a world reeling from the pandemic, future tourism will be rooted in sustainability and traveler confidence. Promoting healthy environmental practices under the USMCA, as well as cooperation on issues of good governance, risk management for individual travelers, and reducing illicit activity could promote both of those goals and attract more tourists.

Rare Earth Elements

Rare earth elements have a variety of uses that may drive the future of energy and security, but the lack of emphasis on their importance in North American trade has left another gap for China to fill. Rare earth elements contain useful chemical properties applicable to a range of industries, from LED lights to weapons systems. These metals are produced through an extensive mining and refining process. The United States was historically a leading producer of these metals and remains the third-largest producer globally. While Mexico has not tapped into its supposed reserves of rare earths, it is the fourth-largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) for mining in the world and has major potential to expand in that area. Notably, since the 1990s China has experienced a near-monopoly over rare earth production and exports, with a 37 percent share of global rare earth reserves. Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping recognized the potential of rare earths and made production a top priority during his liberalization of Chinese markets. A combination of state support by subsequent administrations and lower environmental and labor standards has put China in a position of power in a market inextricably tied to global defense, transportation, and energy.

China’s unmatched dominance in the rare earth sector has the potential to become adversarial and disrupt global supply chains, but there is hope for this sector in North America. Canada and the United States signed a 2019 agreement to reduce reliance on Chinese rare earth imports. Further, Mexico has plans to nationalize a newly discovered lithium mine in Sonora with some of the largest proven reserves in the world, which is currently under Chinese and British joint venture. Both the U.S. Commerce Department and U.S. Defense Department have explicitly recommended an increase in domestic production and stockpiling as a safeguard to potential Chinese manipulation. If the United States labor force shifts towards an increase in rare earth production, continued cooperation and transparency with partners under the USMCA will be important to prevent an escalation of tariffs similar to the 2019 steel and aluminum tariff debacle.

Looking Ahead

Over the next four years, the Biden and AMLO administrations will need to work together on several major areas impacting trade, including fully implementing the USMCA, strengthening the North American supply chain, managing the Covid-19 pandemic recovery process, and negotiating issues surrounding Mexico’s energy sector. A coordinated Covid-19 recovery and vaccine rollout will be the most pressing issue in the coming year, especially since the United States and Mexico have the first and third highest numbers of deaths to the disease, respectively. Mexico’s vaccination plan has been uncoordinated and disastrous so far, and a coordinated strategy for workforce vaccination will be essential to prevent further supply chain disruption. Given that the pandemic has exposed an over-dependency on supply chains in China, companies are already looking to diversify.

The United States, Canada, and Mexico should collaborate to promote the North American market as an attractive supply chain alternative to China and as a keystone to a larger strategy of nearshoring and allied-shoring in the Americas. They should encourage companies to expand capacity in the region and promote the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises, especially in certain essential sectors like pharmaceuticals, PPE, and rare earth minerals. The full implementation of the USMCA will also be vital to the trade relationship, including executing some of the more ambitious parts of the agreement like Mexico’s labor obligations.

Although full implementation of the USMCA will require a major diplomatic effort by both countries, it would produce a more resilient and competitive North American market in the long run. Key issues to address in order to achieve full USMCA implementation include infrastructural and logistical improvements at the border, massive training programs for the young workforces in each country, and open dialogue at the highest levels of each government. In pursuing the United States’ environmental goals, it will be essential for the Biden administration to be honest about the scope of regulations while reassuring the AMLO cabinet of Pemex sovereignty. Increases in free trade often lead to domestic uproar and international dispute, but thankfully the USMCA provides a legal framework for dispute resolution.

Strong cooperation on trade will create an essential basis upon which the countries can cooperate on other issues. Problems of security, corruption, and poverty persist in Mexico, with the country lagging behind the United States and Canada on many socioeconomic indicators. AMLO has attempted to address these issues through social and educational programs such as “Youth Building the Future” and “Sembrando Vida,” which aim to train Mexico’s young workforce and stimulate sustainable agriculture, respectively. Expansion and restoration of stability in trade under the USMCA could give Mexico the economic basis necessary to not only confront poverty and create jobs, but also to implement AMLO’s programs intended to create a more modern and competitive workforce. The United States should collaborate with AMLO to address core issues of poverty in Mexico through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the International Development Bank (IDB). The United States and Mexico should also revisit the charter for the North American Development Bank, so as to focus not only on the U.S.-Mexico border, but also on Mexico’s border with Guatemala and other impoverished parts of the country.

The potential of the USMCA is not limited to trade. The flow of ideas, goods, and people across borders contribute to a North American economic bloc beyond the pragmatics of a trade deal. The strengthening of a North American trade identity, in which the three USMCA nations not only trade with one another but build things together, is unique among free trade deals. The North American economy has the potential to ensure prosperity across the continent, outcompete China and other growing powers on the global market, and become the most attractive destination for international investors.

Presidents Biden and AMLO are at a point of immense opportunity to determine the trajectory of their two nations. Through full implementation of the USMCA and strengthening of their trade relationship, they have a chance to not only foster one of the largest trade partnerships in the world, but to also take the North American regional market to unprecedented heights. There has truly never been a moment in history like this one, and as tectonic forces continue to disrupt global actors, the United States and Mexico can work bilaterally to prevail and become a shining example of cooperation. Restoring trust in the U.S.-Mexico relationship will require diplomacy at the highest levels, transparency about desires, and full implementation of the dispute mechanisms provided by the USMCA.

.

Daniel F. Runde is senior vice president, director of the Project on Prosperity and Development and holds the William A. Schreyer Chair in Global Analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Linnea Sandin is the associate director and associate fellow for the CSIS Americas Program. Isaac Parham is an intern with the CSIS Americas Program.

This report is made possible by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2021 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.