Three ways educators can meet the needs of a rapidly growing student population that brings great strengths, but a long history of being overlooked.

By Conor Williams, The 74.

Demographic change regularly gets discussed as one of those big, inevitable, structural currents reshaping American life. It’s been clear for some years that the United States is becoming more diverse — driven particularly by growth in America’s Latino population.

Some sift through these data and conclude that the U.S’s growing diversity is sure to deliver an “Emerging Democratic Majority” for progressive politicians. At the same time, some fret that these trends are fated to generate anxious, revanchist — even ethno-nationalist — political backlash from blue-collar, white (generally non-Latino) Americans.

But comparatively few have approached the demographic facts as an opportunity to be engaged, or as a situation to be managed. After all, if these trends are as certain as the tides, what is left to be done? This is a mistake — and an abdication of our obligation as citizens in a self-governing democracy. This growing diversity presents schools with a major opportunity to rectify long-standing inequities and reform themselves to help Latino students build on the strengths that they bring to campus.

Data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences suggest that U.S. schools now enroll more than twice as many Latino students as they did in 1995. Indeed, the data suggest that, by 2030, Latinos will make up roughly 30% of all public school enrollment. This should spur schools and policymakers to action, since research suggests that these students bring significant assets to school and — when these are adequately supported — can be some of the country’s highest-performing students.

As a recent UnidosUS report put it, “With the ability to navigate across and between cultural and linguistic differences, Latino students bring a multitude of talents and assets that make our schools — and our country — stronger.” However, U.S. schools have a checkered history of recognizing and valuing that potential.

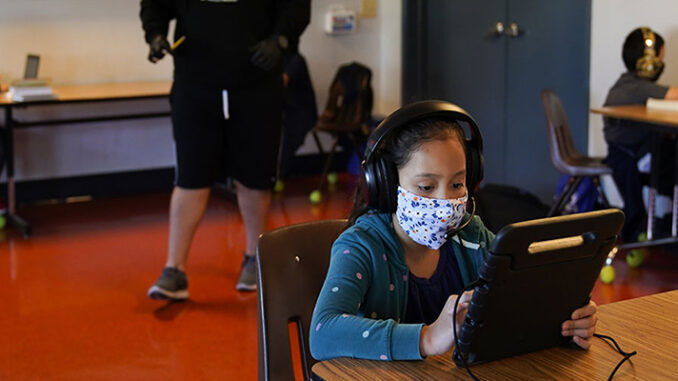

American public schools have historically segregated Latino students from peers of other racial or ethnic backgrounds through a variety of overt and covert methods. This isn’t just a problem from the distant past. English learners, who are disproportionately likely to be Latino, are currently the student group most likely to attend socioeconomically segregated schools. And, as the UnidosUS report makes clear, schools have particularly struggled to adequately support children of these backgrounds throughout the pandemic. This echoes a number of studies finding that English learners and Latinos were often left out of schools’ pandemic learning efforts.

In sum, it is far from clear that American public schools are prepared to provide all Latino students with high-quality learning opportunities in this era of new and growing student diversity. These trends have been building for years, and Latinos have faced inequities in American public education for generations. They will face versions of these injustices next fall. They will almost assuredly still be facing them in 2030 (and beyond).

This will necessarily be a complex project, as American Latinos are profoundly diverse. Latinos in Chicago are disproportionately of Mexican origin, while Latinos in D.C. are more likely to have roots in El Salvador. Latinos in Miami are more likely to have Cuban ancestry, though many in the community have links to Venezuela, Colombia, and other Central American countries. And Latinos are racially diverse, encompassing groups of people who identify as ethnically Latino but also racially white, Black or some other identity. While many Latinos speak Spanish at home, others speak English, both languages, Portuguese, or one of a panoply of Central American languages.

From jazz to mambo to bachata to go-go to pernil to Tex-Mex to churrasco to ceviche, Latino diversity shows up in myriad ways throughout the culture of the United States. Latinos have long been at the vanguard of improving American soccer and lists of all-time great Major League Baseball players are stacked with Latino players from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Venezuela, and beyond (to say nothing of Latino stars in the NBA and NFL).

As such, while policies aimed at improving English learners education in the US are necessary to helping more Latinos succeed (see my recent report on the topic for a series of consensus reform ideas), neither are they sufficient for expanding opportunities to the full range of Latino students. What else can we do?

For one, policymakers at all levels should prioritize diversifying the teaching force in their communities — and across the country. A recent Urban Institute study from Texas confirms that Latino students gain substantive benefits from having some teachers who share their identities. Specifically, the researchers found that Latino students who had Latino teachers in elementary school had higher academic achievement, better behavior and better high school graduation rates.

Meanwhile, current teacher training, credentialing and licensure systems are broadly ineffective at producing highly effective teacher candidates, but are reliable at reducing the linguistic, cultural and racial/ethnic diversity of the teaching force. Fortunately, there is widespread consensus among policy researchers that alternative certification programs such as district-driven “grow-your-own” programs, teacher apprenticeships and residencies, and other fellowship programs are generally effective at diversifying local teacher training pipelines.

And as policymakers commit to teacher diversity, they should pay particular attention to linguistic diversity. Research suggests that EL children — especially Spanish-speaking ELs — gain from enrolling in schools that provide them with bilingual instruction. Yet, these programs are relatively rare, with nowhere near enough supply to meet demand, particularly in light of new enthusiasm for them from privileged, often white, English-dominant families. Most communities won’t be able to grow access to bilingual — or integrated dual language immersion — programs without developing new bilingual teacher training pipelines.

Finally, education leaders should prioritize young English-learning children as they invest in early education programs. While there is ample evidence that early education programs are universally beneficial for children and families, research indicates that Latino children may do particularly well in these programs. Further, many studies show a unique benefit for young English learners.