In many of these cases, immigrants reversed long-standing population declines. More importantly, immigrants’ high rates of entrepreneurship and labor force participation helped boost local economies that had been stagnant for decades.

by Dany Bahar and Greg Wright

Over the past several months, millions of American workers have opted out of the churn of low-paid, dead-end work, producing one of the tightest labor markets in modern history. This exodus has had wide-ranging effects on the economy, perhaps most notably the disruption of supply chains and a shortage of many consumer products. In the past week, we learned that these shortages led to the largest year-on-year increase in inflation in over 30 years. Also worrisome is that Americans’ rejection of front-line work has created a bottleneck in the production chain that is limiting opportunities for these workers’ own advancement. When there are fewer pizza delivery drivers, there are also fewer managers needed to supervise them and fewer accountants needed to pay them.

As others have noted, some of these front-line jobs could be filled from the vast pool of immigrants that are desperate to join the U.S. labor force. This would help relieve the supply chain pressures currently hampering growth, calm inflation, and provide a boost to Americans seeking better careers.

What has gotten less attention is that a new wave of immigrants would allow America’s midsized cities to sustain their recent economic growth, much of which can be attributed to immigration that occurred over the past decade. In fact, the cities with the fastest growing immigrant populations over the period 2010 to 2019 were all medium-sized cities with thriving economies, led by Charleston (SC), Des Moines (IA), Louisville (KY), Columbus (OH), and Nashville (TN). In many of these cases, immigrants reversed long-standing population declines. More importantly, immigrants’ high rates of entrepreneurship and labor force participation helped boost local economies that had been stagnant for decades.

Now, midsized metro areas are experiencing the tightest labor markets in the country, according to a new measure developed by our Brookings Workforce of the Future team. In places like Lincoln (NE), Huntsville (AL), and Omaha-Council Bluffs (NE-IA) there are more than three job openings for each unemployed worker. With front-line jobs in high demand and American workers continuing to quit those jobs at unprecedented rates, the growth potential that these cities have developed is in danger of waning.

And the case for more immigration will soon become even more compelling. The federal infrastructure bill, now passed by Congress, will create hundreds of thousands of jobs building, installing, and maintaining new capital infrastructure. Indeed, capital-intensive projects are, by their nature, job-creating machines that raise wages for workers both within the sector and in related sectors that compete for these workers. At the same time, these infrastructure projects will pull more workers out of sectors like hospitality and retail, compounding shortages of front-line workers. This will be most acute in the fast-growing, midsized metro areas that will receive a disproportionate amount of the funding.

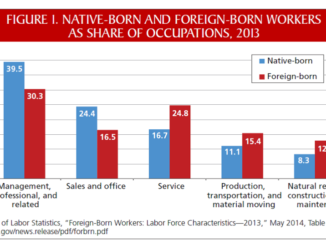

Filling front-line positions with new immigrants would allow Americans to move into a wide range of higher-paying jobs in which they hold a comparative advantage relative to immigrants—for instance managing laborers on a construction site, a position that requires English-language fluency and local knowledge. Research shows that even in “normal times” immigrants are complementary to American workers, and push them up the economic ladder; when companies are clamoring for workers, as they are now, this complementarity should be even stronger.

There will be significant policy work required to achieve these goals. The current visa system is under immense strain, as evidenced by the tens of thousands of work visas that have gone unfilled due to administrative backlogs, the immigrants with long work histories in the U.S. who are unable to renew visas, and the slow progress being made reversing Trump administration immigration policies. Nevertheless, we are in a golden moment for front-line workers and others, who have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to find well-paid jobs with work hours and benefits that lead to a better quality of life. And midsized metros, who have recently seen economic growth rates reminiscent of their heydays half a century ago, have a chance to lead the way.

Today, more than ever, immigration can be a solution to the biggest challenges facing the American economy. Perhaps most importantly, it can serve as a catalyst of upward mobility for American workers.

.

Dany Bahar is a nonresident senior fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution and an associate professor of practice of international and public affairs at Brown University’s Watson Institute.

Greg Wright is a fellow at Brookings in the Global Economy and Development program where he co-leads the Workforce of the Future initiative. He is currently on leave as an associate professor of economics at the University of California, Merced.