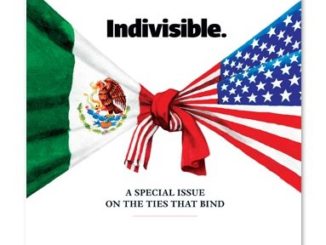

Both countries benefit enormously from existing legitimate cross-border economic ties, and both stand to benefit even more if they can make those ties more competitive, vis-à-vis other global economic powers.

By Earl Anthony Wayne

Watch closely what Mexico and the United States agree on this week. On Thursday, Sept. 9, ministers from both governments will hold the first meeting of a new High-Level Economic Dialogue (HLED) aimed at pursuing economic opportunities beyond the trade issues covered in the new North America trade agreement — the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA — that took effect in mid-2020.

In the USMCA framework, the governments already are overseeing bilateral trade and working through trade differences over such issues as rules for auto production, labor rights, and trade in agricultural products. With the re-initiation of the HLED, however, Mexico and the United States are signaling the need for an additional forum to help institutionalize dialogue and manage their massive bilateral economic relationship.

Mexico is the U.S.’s biggest trading partner and relations with Mexico touch more daily lives in America than any other relationship the U.S. has in the world. The United States relationship plays an even greater role for Mexico. Not only do the two countries trade about $1 million a minute, but they face very tough migration, border management and trans-border crime problems that defy easy solutions.

The HLED was a productive bilateral Cabinet-level working process from 2013 to 2016, but it was dropped by the Trump administration. Many of the important agenda items suffered. By recreating the HLED, the two governments are prioritizing key economic issues that must be addressed though regular engagement and partnership over multiple years.

The administrations of President Biden and Mexico’s President Lopez Obrador have decided they can benefit from working together to better manage cross-border supply chains and trade, promote targeted economic development to reduce migration, and strengthen investment in workers in both countries.

This new effort recognizes the value of learning from the pandemic and the accompanying economic recession that exposed weaknesses in U.S.-Mexico cross-border supply chains and the management of border trade flows. It is important to remember that, not only is there enormous trade across the border to better manage, but before the pandemic there were about 1 million legitimate border crossings each day, feeding the economies of states on each side of the border. If you grouped together the U.S. and Mexican border states, they would amount to the third largest economy in the world.

Both countries benefit enormously from existing legitimate cross-border economic ties, and both stand to benefit even more if they can make those ties more competitive, vis-à-vis other global economic powers, and find ways to make bilateral economic corridors more resilient against future disruptions.

As the U.S. and Mexico struggle to manage the numbers of migrants passing through Mexico and to the U.S. border, they agree on the need to promote investment and economic development in or near their home regions that will provide good jobs for those migrants.

Mexico and the United States have agreed on four pillars of focus for the HLED. On Thursday, they will approve an initial work agenda. The first pillar is “building back together.” The work could include steps the governments can take to support the creation of more resilient and efficient supply chains and to plan for responses to future disruptions such as those faced in the past 18 months. This work could also take up the unfinished agenda for making the U.S.-Mexico border a modern, 21st century border by improving the flow of goods and people with more efficient and secure processes and facilities.

The second pillar is “promoting sustainable economic and social development in Southern Mexico and Central America.” It will not be easy to identify the right mix of economic, financial and development tools and programs to produce good results, and there will be some thorny issues, such as proposals for the U.S. to allow different types of temporary work visas. However, having a regular bilateral forum to work through these challenging issues will be a help to the tough work of finding humane and efficient means to manage the large number of migrants entering Mexico and heading to the U.S.

The third pillar will look at “securing tools for future prosperity.” Officials will explore a range of issues, including enhanced cybersecurity cooperation and managing the evolution of information technology networks that will become increasingly more important in trade across North America.

The fourth pillar is “investing in our people.” One large area for collaboration could be cooperating to promote workforce development. Workers in both countries would benefit from enhanced efforts to apply best practices to upskilling and reskilling of workers in key industries that connect Mexico and the United States. In addition to improved training programs and exchanges for skills education, the countries also might explore how to better align the recognition of the credentials that workers on both sides of the border receive through skills and education programs. Such cooperation could cover professional as well as vocational training and could be targeted to help specific groups such as women, minorities or the disadvantaged.