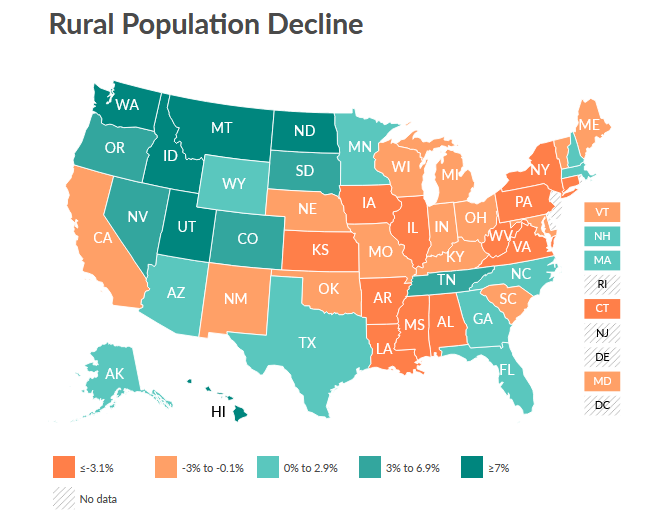

Rural counties lost population since the 2010 census, making it likely they will lose political clout in most states once new data is released Aug. 12 and states draw new legislative and congressional district lines.

by

As states turn to drawing new state legislative and congressional districts after census numbers come out Aug. 12, they’re likely to find that rural, generally conservative areas have shrunk in the past 10 years and stand to lose power in statehouses and Congress.

A Stateline analysis of recent U.S. Census Bureau estimates shows rural areas lost 226,000 people, a decline of about .5%, between 2010 and 2020, while cities and suburbs grew by about 21 million people, or 8%. Only Hawaii, where retirees and remote workers are moving to rural islands, and Montana, which is drawing remote workers from pricey Washington state, saw more rural than urban growth.

Republican state legislatures will try to draw districts that preserve the political power of mostly conservative rural voters, but that task will become increasingly difficult as the population balance shifts toward cities.

“You can’t escape the math. These growing areas are going to grow in their representation,” said David Drozd, research coordinator for the nonpartisan Center for Public Affairs Research at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

Nebraska’s three largest counties, around Omaha and Lincoln, will likely add to their majority of representatives in the unicameral state legislature, Drozd said. It’s possible to keep the status quo by drawing smaller rural districts and larger urban ones—state law allows up to a 10% difference in population between districts—but that’s not a likely outcome.

“I’m sure some rural senators would like to protect those areas, but if you can see they’re intentionally skewed like that, they will be challenged in court,” Drozd said. Republicans have a supermajority in the legislature, but the state’s two largest and fastest growing counties voted for President Joe Biden last year.

Rural counties lost population since the 2010 census, making it likely they will lose political clout in most states once new data is released Aug. 12 and states draw new legislative and congressional district lines. This map is based on U.S. Census Bureau estimates for the period between census 2010 and April 2020. It uses county rural/urban categories developed by the Pew Research Center in 2018.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau estimates, Pew Research Center county categories

Some of the biggest gaps between rural and urban growth are in conservative states that voted for former President Donald Trump in 2020: Cities grew by more than 15% in Florida, South Carolina, South Dakota and Texas, while the rural population of those states either declined (by 3% in South Carolina) or grew slightly (3% in South Dakota). In Arizona, where Republicans control the state government but Biden eked out a victory, the urban population grew more than 16% while the rural population grew less than 3%.

In some states, rural interests have organized to lobby for as much representation as they can keep. Pro 15, a group that advocates for largely rural northeastern Colorado, asked the state redistricting commission not to dilute the power of rural counties by dividing those voters into districts dominated by urban voters.

Colorado’s rural counties grew 4%, a fraction of the state’s 17% urban growth, according to the census estimates.

“If they start pulling our counties out it will dilute our rural voice,” Cathy Shull, the director of Pro 15, told Stateline, adding that rural areas support the whole state with agriculture, tourism and energy from oil, wind and solar power.

Rural residents depend on elected representatives to keep Colorado River water flowing to their farms and to help them protect their livestock from predators.

“Progressives in the city might want to reintroduce the gray wolf and think it was a really cool thing, since it wasn’t going in their backyard. And what if there’s nobody to speak for the people with sheep and cattle getting killed?” Shull said.

In states such as Texas, conservative rural areas have been tacked on to small slices of growing liberal cities to help maintain Republican power.

“When I lived in Dallas, I was in a [congressional] district that went way out into rural East Texas. My vote was diluted but I don’t think East Texas was happy about it either,” said Michael Li, an attorney and redistricting expert now at the progressive Brennan Center for Justice in New York City.

When urban and rural areas are mixed, he said, representatives may displease one of the two constituencies. Often, urban businesses can sway them with big donations that rural interests can’t match, he said.

“The rural vote may win but that doesn’t mean the rural area isn’t impacted,” Li said.

The Stateline analysis was based on Census Bureau estimates of county population changes between the 2010 census and April 2020. Those estimates, released in July, were derived from administrative records of births, deaths and housing construction. The detailed head count data used for redistricting will be released Aug. 12.

That tally could have some better news for rural areas. Statewide, Nebraska’s 2010 full count exceeded population estimates by about 20,000, Drozd said.

The legislative lines that lawmakers and redistricting commissions draw based on the 2020 census will remain in place for a decade. But the pandemic already may have made them out-of-date. Increased opportunities for remote work and feverish real estate markets have spurred many city residents to seek more affordable rural alternatives.

After the census count concluded in April, there were reports of large-scale moves out of cities as the pandemic peaked, though more recently there have been signs that young workers are returning to urban jobs and looking for housing there.

But the 2020 numbers will stand until 2030, and they mean more power for large Sun Belt cities that lean Democratic, said William Frey, a demographer at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

“Despite the suburban and pandemic-driven city exodus movement in the last half of the 2010s decade, population shifts in the census-to-census period should bolster large city and metropolitan representation in congressional districts at the expense of smaller areas,” Frey said.

But Li of the Brennan Center said the 2019 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Rucho v. Common Cause could be seen as “a green light” for states to gerrymander by political party. The high court ruled that partisan gerrymandering might be “incompatible with democratic principles” but that it was up to states, rather than the federal courts, to curb it.

Other analysts note that in some states, conservative suburbs are maintaining their Republican bent as they grow.

In North Carolina, for instance, “in addition to the state’s deep red rural component there are several large suburban counties that are 60% Republican and that hasn’t budged much over the last decade,” said J. Miles Coleman, co-author of a recent University of Virginia Center for Politics analysis. The study predicts that redistricting could give Republicans at least six additional U.S. House seats in the South.

.

Tim Henderson covers demographics for Stateline. He has been a reporter at the Miami Herald, the Cincinnati Enquirer and The Journal News in suburban New York. Henderson became fascinated with census data in the early 1990s, when AOL offered the first computerized reports.