A decade’s worth of data from 1.3 million Florida students yields a novel finding: Having more immigrant peers can boost scores for U.S.-born students

by Asher Lehrer-Small , The74

This article was originally published at The 74.

March marked an all-time monthly high in solo youth crossings at the U.S. southern border. Those children and teenagers could be an unexpected boon for native-born students should they reach American classrooms, a timely new study suggests.

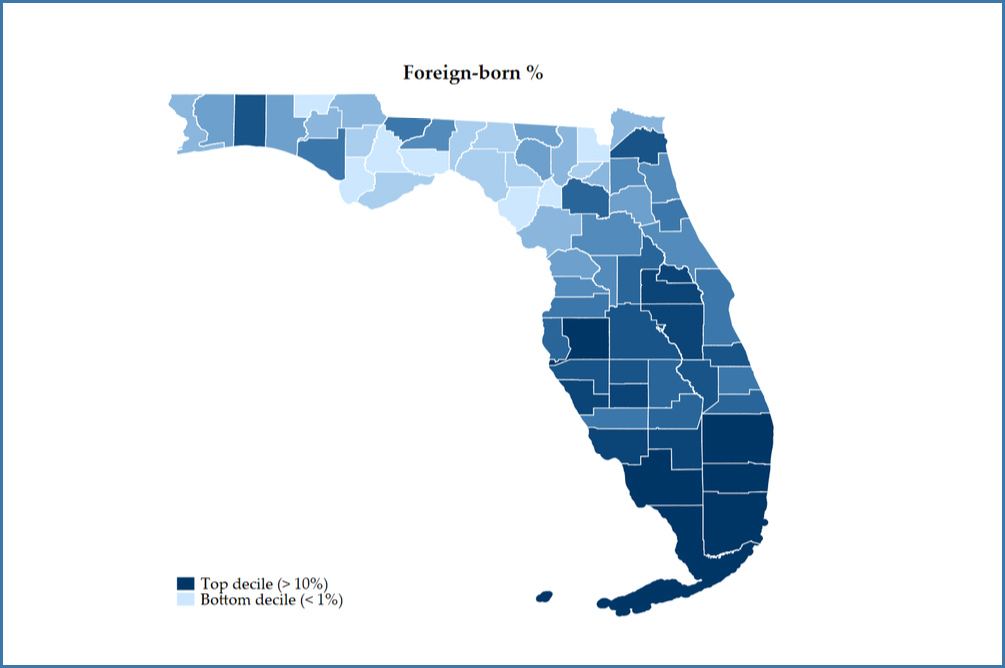

The research, which analyzes a decade’s worth of data from over 1.3 million Florida students, links the presence of immigrant classmates with gains in academic performance for students born in the U.S., especially for Black and low-income youth.

“Instead of seeing evidence of immigrants harming native-born students, we actually find evidence that immigrants at minimum do not harm and [often] help native-born students academically,” co-author David Figlio, professor of education and economics at Northwestern University, told The 74.

In the past, research on the topic had been complicated by the fact that immigrant youth tend to enroll at schools educating higher shares of underserved students. At the same time, whiter and more affluent kids may decide to change schools when immigrant students move to their district, a well-documented trend known as white flight.

Those factors together can create a statistical mirage in which immigrants appear to cause lower academic performance for native-born students, as a 2011 study of schools in Denmark concluded. Similarly, others have argued that immigrant students might consume additional resources that limit funds for others.

But Figlio and his co-authors took a novel approach — and uncovered an opposite effect.

Their study, published as a working paper in March by the National Bureau of Economic Research, compared sets of siblings who theoretically had all factors in common (family characteristics, race, socioeconomic status) — except one: exposure to immigrant peers.

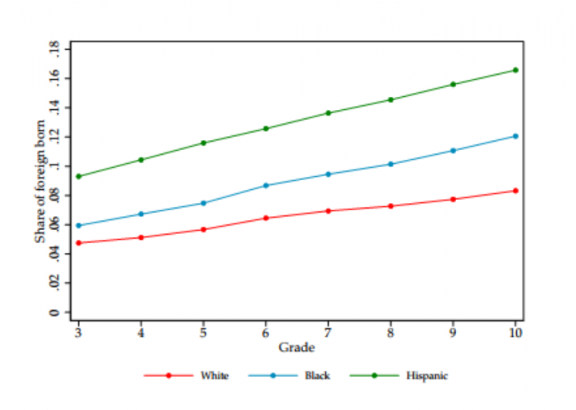

Due to fluctuations from year to year, many U.S.-born students have different shares of immigrant classmates than even their own family members. Looking at those cases, the researchers found a significant boost to native-born students from having immigrant peers.

Holding factors like race and poverty constant, students who had 13 percent immigrant classmates achieved higher reading and math test scores on average than those who had only 1 percent exposure — a difference equivalent to nearly 10 percent of the gap in scores between students whose mothers had completed high school and those whose mothers hadn’t. Black and low-income students saw benefits that were twice as large.

The ‘true believers’ in the American dream

Students’ drive may be a key reason for the effect, according to Figlio.

“Immigrant students in the United States tend to come from families that are very highly motivated,” he said. “They’re driven for success,” which can have a “spillover effect” in the classroom.

The findings offer a new datapoint on the potential impacts of immigration, at a moment where debate on the topic has reached a fever pitch. Currently, over 20,000 migrant youth are in government care at border facilities, according to recent reporting.

The positive effects found in the working paper don’t surprise Patricia Gandara, a specialist in immigrant students who works as a professor of education at UCLA. English language learners, who sometimes but not always overlap with those who are foreign born, often outperform English-only students once they reclassify as fluent speakers, research shows.

“There’s a real spark in these kids,” Gandara told The 74. “They know their families have made tremendous sacrifices.” In turn, immigrant kids often see school as their ticket to success in this country, and set their sights on higher education. “They’re the true believers in the American dream,” said Gandara. “They really apply themselves.”

Especially for students of color or low-income students who might feel left behind by an education system that disproportionately discourages and disciplines kids of their background, having classmates with a college-going mindset can have a big impact, she says.

“Having these peers who have higher aspirations, who’re talking about graduating high school, going to college, it rubs off.”

A ‘win-win’

But despite migrant students’ success and positive impact on peers, Figlio and his co-authors also found that white and affluent students often abandon schools with high proportions of immigrant youth. White students in the dataset on average had only a 6 percent exposure level to immigrant students, while native-born Black and Hispanic students had 8 and 12 percent levels, respectively.

Those numbers frustrate Rosario Quiroz Villareal, an education policy entrepreneur at Next100 who herself grew up as an undocumented student.

“The quicker we can wrap our minds around [the positive effects of diversity] and embrace that, the quicker that our school systems can move toward ensuring that they are also creating environments where students are learning from each other, embracing each other,” she said.

It’s a “win-win” to have racially and socioeconomically diverse schools, added Conor Williams, a fellow at The Century Foundation and regular contributor to The 74. Integrated classrooms give a boost to all kids, but especially lower-income students and students of color, he told The 74.

But though the school integration numbers may be rock-solid, Figlio, the Northwestern University researcher, says that there are many factors in the analysis on immigrant students that still need to be clarified. His team’s dataset comes from Florida, but whether students in other states would yield the same results remains to be seen.

Additionally, as Gandara points out, the study adopts a narrow definition of migrant students, including only those who themselves were born in another country (or in Puerto Rico). She wonders, how would the results change if the more than 11 million students born in the U.S. to immigrant parents were taken into account?

“This is a small slice of what we generally think of when we think of children in immigrant families,” said Gandara. “It’s hard to know how this might generalize out.”

Figlio hopes future research will address those questions. “This is not the last word. This is the next word,” he said.

But for the meantime, according to Figlio’s study, the results from this group of students, in this setting are clear.

“Immigrants can basically create a rising tide that lifts all boats,” said the Northwestern professor.

Asher Lehrer-Small is an Editorial Fellow at The 74.