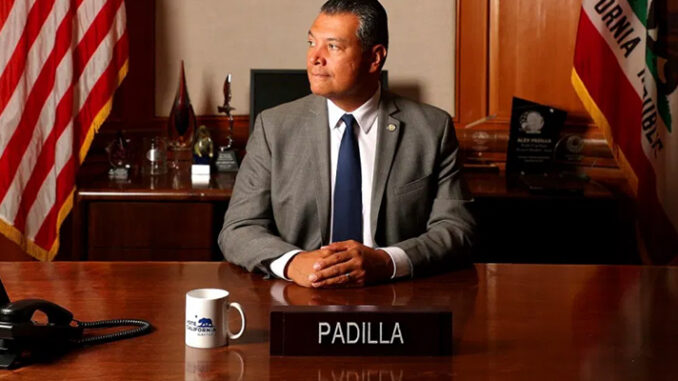

California’s new senator, who filled Kamala Harris’s seat, is hoping to speak for his fellow Latinos. That won’t be easy.

by Christian Paz

Alex padilla was radicalized early. The young man was 21, freshly graduated from MIT with a mechanical-engineering degree, and he had returned to his childhood home in the San Fernando Valley to figure out his next step. From the television in the living room, Padilla heard a grim voice offer a warning: “They keep coming.” Grainy black-and-white video showed shady figures wading through cars waiting in line at the crossing in San Ysidro. “Two million illegal immigrants in California. The federal government won’t stop them at the border, yet requires us to pay billions to take care of them,” the voice added, menacingly.

“Who is it that they’re referring to? Latinos coming from Mexico to California to work?” Padilla thought. “That’s the big threat?” The people in the ad could just as easily have been his family, so when the time came to protest anti-immigrant legislation in the state, he eagerly joined. Padilla and his mom gathered a group of neighbors to attend the massive 1994 demonstration in downtown Los Angeles against a ballot referendum that would limit immigrants’ access to public services. In doing so, he put himself on a path that would lead him to the Senate.

Memories of that segregated California still have an influence over the man now representing the country’s most populous state. Padilla, who was sworn in on Inauguration Day, finds himself in a unique moment in Latino political history, both as the first Latino senator from California and as a first-generation Mexican American, an identity that’s uncommon in the top levels of the U.S. government. (Padilla was appointed to finish Kamala Harris’s term, which ends next year.) He came of political age while California was experiencing a rocky transformation from a Republican-dominated, majority-white state into a solidly blue state with a Latino plurality. Now he’s in Washington as America undergoes a similar demographic change, with Black and brown Americans becoming bigger players in the electorate.

Claiming a spot as a national Latino leader won’t be easy. Latinos in the United States remain divided across class, education, nationality, and geography. The 2020 election reminded the country, and the Democratic Party, that while many of these voters share a language, not much else cuts cleanly across the Latino community—even the term Latino was invented rather recently. That reality presents a major challenge for anyone hoping to speak for or to American Latinos. Any politician runs the risk of flattening the diversity of Latinos as he tries to reach as big an audience as possible, and a generic appeal to identity could turn off those who don’t see themselves reflected in any one person. And to be clear: The audience Padilla is trying to reach is big. Latinos are already the country’s largest minority, and their share of the American electorate will continue to grow over the next decade—a Latino becomes eligible to vote every 30 seconds. Most of them are Mexican American, like Padilla himself.

Padilla told me that, through his work in the Senate, he wants “to ensure that the American dream my family has experienced in the San Fernando Valley is still within reach.” The past four years have tested that dream for millions, especially Black and brown Americans. Can Padilla convince them that the Democratic Party will keep it alive?

Padilla made two promises in high school that changed the course of his life. The first was to a family friend who’d just completed his first year at MIT, and who pestered Padilla about applying to the elite school. Like Padilla, the friend was from Pacoima, a majority–Mexican American, working-class neighborhood 20 miles from downtown Los Angeles. At the time, Padilla had his heart set on a university with a good engineering program near a beach, but the friend bothered him so much that he vowed to apply.

Then there was the promise to his parents. “I knew that if I got in, I needed to go,” he told me in a recent interview over Zoom. “Yes, it was a chance of a lifetime for me to get a good education. But it would be the fulfillment of my parents’ dreams. It’s why they came to the United States.” His parents, Lupe and Santos, a housekeeper and a short-order cook, respectively, feature prominently in the stories Padilla tells about his political career. (Lupe died in 2018; Santos lives in the same home that Padilla grew up in.) His voice thickened when he told me about how his dad would interrupt him late at night while he was working on school assignments to remind him of his duty to graduate college: “Mi hijo, cuando crezcas, quiero que trabajes con tu mente, y no con tu espalda.” “Son, when you grow up, I want you to work with your mind, and not your back.”

“There’s a lot of honor in manual labor, and I don’t want that to be misrepresented, but that was his way of saying he wanted better for us,” Padilla said. So when the time came to leave the Valley, he packed everything he had in two tote bags and flew to Logan International Airport to spend four years in a drastically less brown town: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

MIT was where Padilla first encountered the striking diversity of the country’s growing Latino population. In 1990, when he arrived, the school was overwhelmingly white, which made befriending other Latino students an easy—and necessary—task. Padilla’s dorm room on the second floor of Bexley Hall quickly became a spot for Puerto Ricans and Central Americans from New York and Cuban Americans from Florida to meet with Mexican Americans from Southern California. They talked about how different they were from their wealthy white classmates, and how they needed to band together to thrive in a white-dominated space. “God knows how many Latinos there were, but we would stick together, and it was actually pretty crucial because we couldn’t just up and leave for home for the weekend,” Xavier Velazquez, a childhood friend of Padilla’s and his sophomore-year roommate, told me. During holidays such as Thanksgiving, Padilla and Velazquez would await care packages from home and share their tamales, nopal cacti, and jalapeño and piquín peppers with other classmates. Long after getting the chance to move to a more spacious single room, Padilla continued living in the double in order to provide his friends with a gathering space, Velazquez said.

The California that Padilla returned to after graduating was less inviting than the community he’d built at school, and the state’s political clashes would forge a new generation of young Latino activists. Like others of that generation, Padilla was galvanized by Proposition 187—the referendum that he and his mother protested right after he left MIT—as well as the openly anti-immigrant reelection effort of then–Republican Governor Pete Wilson, who boasted in ads of his attempts to punish undocumented immigrants. Proposition 187 would have denied public services, such as nonemergency health care and public education, to people suspected of being undocumented, and many Latinos, including Padilla, saw it as an attempt to scapegoat immigrants for the recession California had experienced earlier in the 1990s. Although voters approved the referendum, it faced swift challenges in the courts and was never implemented. It did, however, change California politics, by compelling Latinos to acquire citizenship, vote, run for office, and shun the state GOP.

All of this was happening as Padilla was about to take his first step on the political ladder. He spent about a year at an engineering desk job before he started working in politics professionally, including as the campaign manager for Tony Cárdenas’s state-assembly bid in 1996. He had a knack for connecting with constituents, Cárdenas, now a five-term U.S. representative from the San Fernando Valley, told me. Voters and campaign volunteers “saw in me, and they saw in my general, Alex, themselves and their children and their community.” (Earlier this year, Padilla crashed on Cárdenas’s couch while looking for a D.C. apartment.)

Within just a few years, Padilla would run for Los Angeles City Council, and weave his youth, working-class background, and Latino identity into his pitch to voters and potential endorsers—including labor unions, whose white bosses led a growing Latino membership. In the days after the September 11 attacks, Padilla, then the first Latino and youngest city-council president, served as the city’s acting mayor, speaking to Los Angeles from the steps of city hall and giving TV and radio interviews in both English and Spanish. (Mayor James Hahn was stranded in Washington at the time.) “He had to rise to the occasion and provide a sense of leadership and guidance and comfort to the residents of Los Angeles, and the fact that he was able to do that in two languages was particularly impactful,” Arturo Vargas, Padilla’s longtime friend and the CEO of the NALEO Educational Fund, a Latino civil-rights group, told me.

By 2006, Padilla was in Sacramento, where he would work for about 14 years as a state senator and secretary of state. Though a wide range of topics fell under his purview, voting rights and ballot access—both of which are now core Democratic Party priorities—emerged as Padilla’s loudest areas of advocacy, and they’ve remained so. As secretary of state, he ushered in same-day voting registration, allowed 16- and 17-year-olds to preregister to vote online, and automatically registered Californians when they got their driver’s license, among other measures. (He also welcomed national attention when he refused to cooperate with the Trump administration’s first round of voter-fraud investigations, in 2017.) Padilla “transformed” the secretary of state’s office, María Teresa Kumar, the CEO and founding president of the activist group Voto Latino, told me. “The fact that 16-year-olds can preregister—it’s not small, because the majority of [those young people] are Latinos, Asians, and African Americans. He enfranchised them.” Voto Latino ended up pulling its voter-registration efforts out of California because “the government did its job,” Kumar added. Four and a half million more residents were registered to vote when Padilla left office than when he entered; now nearly 90 percent of eligible Californians can vote.

Padilla said his experience running California’s elections is behind his support for the election-reform bill H.R.1, a new Voting Rights Act, and comprehensive immigration reform. Those measures would expand the body politic by making the ballot box more accessible to Black and Latino Americans, and they’d boost voter trust in the legitimacy of the political system, he argues. The system could then better reflect the diversity of Latino communities and their complex priorities—a core aim of his agenda. And yet, in his effort to improve representation and expand voter participation, Padilla will run into familiar challenges—and the perennial question of what Latino voters actually want.

Democrats, stunned by Donald Trump’s improved performance with Latinos in the November election, have directed renewed attention to Latino voter persuasion and turnout efforts ahead of next year’s midterms. But the simplest way to find out what Latinos want—asking them—is often overlooked when Latinos aren’t in the rooms where conversations about Democratic strategy are happening.

Underrepresented in nearly every level of government and party politics, Latino politicians face notable obstacles when aspiring to a bigger spotlight, and have few models to follow when venturing into national politics. (Senators Marco Rubio of Florida and Ted Cruz of Texas are prominent Latino leaders, but they’re both Republicans.) Latino politicians are often pulled between the need to represent a politically neglected community and pressure by national media and party leaders to speak about “Latino” issues. They must talk about their identity without giving the impression that non-Latino voters are being left out of their vision. And they must be careful to avoid peddling an amorphous form of racial solidarity among people of color. “I knew that a lot of people would think, Hey, if you were to release an immigration plan, people are going to think you’re the brown guy doing brown things,” Julián Castro, then a Democratic candidate for president, told the late-night host Trevor Noah in 2019 about this struggle.

There’s also the challenge of calibrating as broad a message as possible without flattening the needs and lived experiences of different communities. In the Democratic primary, Castro pitched himself as a Latino trailblazer and highlighted his family’s activist and immigrant roots in an expansive appeal to Latinos, but he was never able to build up enough national support, Latino or otherwise, to sustain his campaign.

As Padilla aims to build his national profile, he will have to wrestle with creating a message that sounds authentic enough to Latinos but is appealing to many more people, Lisa García Bedolla, a political scientist and the dean of UC Berkeley’s Graduate School, who has studied the importance of Latino political representation, told me. Racial or ethnic appeals for solidarity fall flat when they don’t seem genuine or specific.

“If he were just talking about being a Latino senator in the generic sense, and not grounding it in his particular story, then you do run the risk of people saying, ‘Well, you don’t speak for me,’” she said. “What he’s going to be trying to do over the next few years is really demonstrate that he’s not just representing Latinos, but that he’s representing a universal set of values that come from his Latino experience.”

How Padilla articulates those values and explains his personal story may determine how big and diverse his audience will end up being—geographically, ethnically, and ideologically. He’ll have to come up with a pitch that cuts across racial and class divisions, and “highlight the fact that he sees inequities and policies through the lens of the disenfranchised, and use that as a way to build a coalition around ballot access and ballot reforms,” García Bedolla said. Because of his experience as California secretary of state, “he knows the voting-rights history of this country and the efforts to disenfranchise people,” Laura Gómez, a Chicana scholar and professor at UCLA’s law school, told me. “Then, by virtue of having been to an East Coast school, he’s been exposed to [other Latino groups], and he needs to continue to build bridges to Puerto Ricans and Cubans and Dominicans and other Latinos.”

Padilla will also face a persistent challenge: being strategic when speaking about the border, undocumented immigration, and racism, which together are seen by many non-Latinos as the only “Latino issues.” “The challenge for Latino politicians has always been the ability to try to transcend their Latino identity,” the conservative Latino political consultant Mike Madrid, who has known Padilla for decades, told me. “There’s a set notion in this country of what Latino issues are,” but more Americans should also see economic concerns, such as income inequality, poverty, and homelessness, as “Latino issues.” Recasting the immigration debate could help that shift: Though Padilla has already carved out immigration reform as one of his top priorities in the Senate, he is framing it as a pragmatic economic cause, not just a moral issue, saying he’s open to piecemeal reforms such as his bill to grant citizenship to 5 million essential workers. Redefining the “Latino issues” label would not only help other Americans better understand what Latinos’ real concerns are, but also improve Democrats’ appeal to a broader swath of Latinos, including those who have drifted toward Republicans and who may not feel solidarity with the plight of recent immigrants or other people of color, Madrid said.

Though still solidly blue, the Pacoima that Padilla grew up in has plenty of those voters: The area trended toward Trump in November. Over the past two decades, Pacoima has produced a new cohort of upwardly mobile, second-generation Latinos who aspire to the middle class—much like the thousands of young Latinos across the country who are entering the electorate every year. Depending on their education and profession, these young Latinos may vote more like white Americans.

Indeed, Padilla’s future (not to mention his party’s) could hinge on whether he can help Democrats speak to voters attracted to the Republican creed of individualism and economic opportunity. Becoming a senator is “a tremendous opportunity, a responsibility, not just for our community—especially for our community—but to so many others like it,” Padilla said.

Though he doesn’t have a major Republican challenger yet, Padilla’s conservative critics will likely try to tie him to the state’s Democratic leadership, including Newsom, a close ally who is all but certain to face a recall election later this year. Fueled by anger at Newsom’s pandemic management and the state’s unemployment crisis, the governor’s opponents have collected enough signatures to trigger a recall under the state’s laws—a vote that would happen this fall, as Padilla’s 2022 campaign kicks into high gear. Padilla critics could also try to use his progressive policy positions, including his support for the Green New Deal and expanded voting rights, to paint him as a left-wing radical. During his 2018 campaign against Padilla, Mark Meuser, a Republican attorney, questioned whether the then–secretary of state was allowing noncitizens to vote, an unsubstantiated claim that Republicans often level against Democrats. Meuser told me that he hasn’t decided if he’ll challenge Padilla in 2022, but said he’ll make a final decision after the potential recall.

As the time in our Zoom chat dwindled, Padilla and I talked a bit about his first election, for the city council’s seventh district. Before starting his campaign, Padilla had sought out the counsel of his dad’s brother, his padrino—a “typical Mexican man of few words”—who pressed him on why he was running. Padilla made his case, of the need to have the community represented by someone who knew it, who would patch up the potholes, update the local library, and listen to his neighbors’ concerns. When Election Night rolled around, his padrino missed the victory party because he had the flu, but Padilla went to see him the next day, jumping up and down and shouting, “Ganamos—we won!”

In a slow and steady tone, his padrino replied, “Bueno, hijo, ahora hay que cumplir.” “Well, son, now it’s time to deliver.”

.

Christian Paz is an assistant editor at The Atlantic.