The last election’s most unexpected twist is framing one of the most urgent questions confronting both parties today: What explains Donald Trump’s improved performance among Latino voters?

The president who began his first national campaign by calling Mexicans “rapists,” drug smugglers, and criminals; who labored to build a wall across the U.S.-Mexico border; who separated undocumented children from their parents; who sought in court to end the “Dreamers” program; who maneuvered to reduce virtually every form of legal immigration; and who told Democratic women of color in the House of Representatives to “go back” to where they came from—that president won a higher share of Latino voters in 2020 than he did four years earlier, according to every major exit poll and precinct-level analysis of last year’s results.

Still, election observers and Latino-vote experts disagree about what, exactly, those results mean—in particular whether they represent a reversion to Latinos’ traditional level of support for Republicans, or whether they’re the beginning of a lasting GOP improvement that could reshape the electoral landscape in 2022 and 2024. “That’s the big question everybody is trying to answer right now, and I don’t know that we have a definitive answer,” the Democratic pollster Stephanie Valencia, the co-founder and president of EquisLabs, told me.

Trump’s gains were most dramatic in two places: South Florida, with its large population of Latinos from Cuba and Central and South America; and South Texas, where Trump posted head-turning improvement in rural and small-town communities throughout the Rio Grande Valley that are mostly Mexican American. But all the principal data sources on the 2020 results also showed Trump advancing with Latinos across a wide range of states. “There was this baseline shift all across the country,” Valencia said. “It did not just happen in Texas and Florida.”

Democrats have long considered Latinos a cornerstone of what I’ve called their “coalition of transformation,” and assumed that more of these voters in the electorate translates to a widening advantage for their party. Trump’s performance has introduced slivers of doubt that the equation is that simple. In the near term, some of the key factors that lifted Trump among Latinos could help Biden if he runs again in 2024. But a close examination of last year’s results suggests that neither party should be entirely confident about the direction of this huge, but still dimly understood, voting bloc.

One reason for the uncertainty about the meaning of Trump’s gains: The major data sources (which range from network exit polls to the Pew Research Center’s “validated voters” study) conflict over exactly how well he performed with Latinos both last year and in 2016. “There’s no official number, and we are never going to have one,” says Sergio Garcia-Rios, the director of polling and data at Univision and a government and Latino-studies professor at Cornell University.

Generally speaking, the sources showed Hillary Clinton beating Trump among Latinos by nearly 40 percentage points in 2016. In 2020, they showed Joe Biden beating Trump by around 30 percentage points. The Democratic polling firm Latino Decisions has long argued that the exit polls understate Democratic strength among Latinos (because, it says, pollsters don’t interview enough Spanish speakers, who lean more toward the party). But even its benchmark national poll last year, conducted on the eve of the election, showed a big gain for Trump that reduced his deficit with Latinos by nearly one-third compared to 2016.

Although Trump’s advances were real, he still faced big deficits among Latinos in most places. The exit polls showed Biden winning about 60 percent of the Latino vote in Georgia, Arizona, Nevada, and Texas. In precincts where Latinos constitute a large majority of the population, Biden won about three-fourths of the votes in Arizona, Nevada, New York, and Wisconsin; nearly two-thirds in Texas; and about three-fifths in Georgia and Florida (outside of Miami-Dade County), according to an analysis from UCLA’s Latino Policy and Politics Initiative. If Trump won about one-third of Latino voters nationally (the figure most analysts agree on), that’s roughly the same share won by several previous Republican nominees, including John McCain in 2008, George W. Bush in 2000, George H. W. Bush in 1988, and Ronald Reagan during his two races in the 1980s. (George W. Bush did better than that in 2004.)

Given this history, Rodrigo Domínguez-Villegas, the research director at the UCLA center, says he views Trump’s 2020 performance with Latinos mostly as a reversion to the mean after a low ebb in 2016. “It was going back to the historic numbers for the Republican Party,” he told me. “Latino voters still prefer the Democratic candidates by pretty large margins. In some places, [there were] smaller margins than 2016, but nothing out of the ordinary.” Garcia-Rios takes a similar view. “Because Trump came along, we were expecting Latinos to immediately become 100 percent Democrat. And that’s unrealistic,” he says. “For the most part, Latinos are Democratic, but we shouldn’t be that surprised that 20 or 30 percent voted for Republicans.”

However, other analysts aren’t nearly as sanguine. “Were it any other conventional Republican incumbent president, it might not be so shocking,” Fernand Amandi, a Miami-based Democratic pollster, told me. “But Trump staked out such a hard-core white-supremacist type of rhetoric [and] anti-immigrant, anti-Latino framing that it was shocking, really, to me.”

Biden’s showing not only slipped from Clinton’s and Barack Obama’s numbers in 2016 and 2012, respectively, but also continued a Democratic erosion among Latinos that was evident in some states during the 2018 midterms, other alarmed Democrats point out. In its private briefings to Democratic groups, Catalist, a Democratic targeting firm that examines individual voters’ history, has stressed the continuity between the GOP’s gains among Latinos from 2016 to 2018 and Trump’s further advance in 2020.

Analysts have proposed multiple theories to explain Trump’s improved showing, but upon close inspection, most of those explanations appear inadequate to fully explain the shift. These theories, which center on different demographic fault lines running through the Latino community, are worth examining in turn.

One holds that the Democrats’ problem was uniquely among Latino men, and indeed both the exit polls and a competing measure from AP/VoteCast showed Biden winning just 59 percent of them. In the history of the exit polls, the only other Democratic nominees to fall short of 60 percent among Latino men were John Kerry in 2004 and Jimmy Carter in 1980. Two oft-cited reasons for Trump’s gains (as I’ll discuss more below) are that men are more receptive than women to Republicans’ cultural arguments, and that they might have been more responsive to Trump’s emphasis on reopening the economy over protecting public health during the pandemic. But many analysts I’ve spoken with also agree that some Latino men responded to Trump’s swaggering and belligerent persona. “The authoritative nature of Trump does appeal to certain members of the Latino community, especially males, and so it’s nothing that you can ignore,” Democratic Representative Ruben Gallego of Arizona told me.

But Trump’s appeal among Latino men can’t be the full story. The major data sources show that while Biden won two-thirds or more of Latino women, Trump also improved among them relative to 2016. By historic standards, the Latino gender gap recorded in the exit polls was large, but not nearly the largest seen in the past 40 years. More was involved than just a localized problem with men.

A similar pattern emerges when examining another key division in the Latino community: religion. In election years when Republican presidential candidates perform well with Latinos overall, they typically perform very well with Protestant Latinos—many of whom are culturally conservative evangelical Christians. George W. Bush, for instance, won a majority of Latino Protestants in 2004, according to the exit polls. Last November was no exception: VoteCast showed Trump taking a clear majority of these voters, while the exit polls gave him nearly half of all Latino Christians who don’t identify as Catholics—a big jump from 2016. But again, that doesn’t seem to be the entire story. Although the exit poll showed little change among Latino Catholics, the VoteCast poll suggests a small Trump gain—a conclusion seconded by the research Valencia’s EquisLabs has done so far. Although “there was a larger move, percentage wise, among Protestant evangelicals … there was a swing among both” evangelicals and Catholics, Carlos Odio, a co-founder and senior vice president of EquisLabs, told me.

National origin is another major dividing line among Latinos. A poll from Latino Decisions showed that, compared with Clinton, Biden suffered an especially significant decline among voters with roots in Central and South American countries, and that he also lost a majority of Cuban Americans (who had narrowly backed Clinton). This trend is apparent in the election results from South Florida. In 2016, Clinton won Florida’s 26th Congressional District, which has large populations of all three groups, by a resounding 16 percentage points. In 2018, Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell ousted Republican Representative Carlos Curbelo from the seat. But in November, Trump carried the district with nearly 53 percent of the vote, and the Republican candidate, Carlos Gimenez, dislodged Mucarsel-Powell. Why the change? This was one place where Republicans succeeded in tattooing Democrats with the label “socialists.” “The term socialism is extremely toxic in a lot of Latin American communities; there’s a lot of trauma associated with that word,” Curbelo told me. “Republicans were very effective in pinning that label on Democrats.”

Still, Latinos’ movement toward Trump extended beyond those particular communities. The Latino Decisions survey showed that, compared to 2016, Trump narrowed his deficit among both Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans by about 15 percentage points. Beyond his dramatic improvement in South Texas from 2016, Trump also ran five to eight points better in predominantly Mexican American congressional districts across California, and improved notably in New York City districts whose residents have roots in Mexico and Puerto Rico (including the one represented by Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez). EquisLabs’s analysis showed Trump improvement in heavily Latino precincts even “in Massachusetts and New Jersey—not battleground states where Trump was spending a lot of money,” Odio told me. In some ways, Trump’s gains in places where he didn’t target resources might be the trend that unnerves Democrats most of all.

Because Trump’s advances were not confined to any one or two Latino subgroups, analysts are turning toward more crosscutting factors for explanation. That includes campaign tactics during the pandemic. Many Democrats I’ve spoken with believe that renouncing virtually all in-person organizing and campaigning was especially damaging for Democrats among Latino voters—many of whom are less connected to daily political news and often need more direct encouragement to turn out on Election Day. “Taking your army off the field as Democrats did, unilaterally, in almost every county” and thereby giving Republicans “complete control of the field—being at people’s doors … being in the bars, and being in the barrios—that was stupid on our part,” Beto O’Rourke, the 2018 Democratic Senate candidate in Texas, told me.

Democrats also credit the massive digital-advertising effort the Trump campaign aimed at Latinos, as well as the ocean of disinformation its allies created to smear Democrats. “Trump probably invested more money and more resources, both independently and from his campaign, to reach and communicate with Latino voters than any Republican candidate did since George W. Bush,” Valencia told me. The Trump campaign’s targeting was “very sharp,” she said, including extensive advertising on YouTube channels popular with younger Latino men and the deployment of Latino influencers in South Florida. Advertising and organizing don’t tell the whole story, though: The Democrats invested heavily in Latinos too (though later than Republicans did). And even in states where the Democratic voter-turnout operation was sophisticated, such as Arizona and Nevada, Trump improved from 2016.

Among Latino activists and Democratic operatives, one theory that drew significant attention came from the Democratic data analyst David Shor: “What happened in 2020 is that nonwhite conservatives voted for Republicans at higher rates; they started voting more like white conservatives,” he told New York magazine in a widely discussed article in early March. The best evidence from the exit polls suggests that he’s right, according to detailed results provided to me by Edison Research. In 2020, Trump carried Latinos who identify as conservative by nearly 40 percentage points—roughly five times his advantage with them in 2016. By contrast, he made only a small gain among Latinos who identify as liberal, and he lost ground among self-identified moderates.

Shor offered two other theories that provoked substantial debate, but there’s disagreement among Democrats about their accuracy. The first: Shor believes that large numbers of Latinos who voted for Clinton in 2016 switched to Trump four years later. Although they agree that some switching occurred, Valencia and Odio (among other Democratic analysts) believe that most of Trump’s improvement came from turning out Latinos who didn’t vote at all last time, just as he did with non-college-educated and rural white voters. (Still, that’s hardly reassuring for Democrats. Valencia and Odio’s research has found that those new Latino voters are predominantly young, male, and less assimilated into mainstream American culture; if Democrats can’t reach them, they say, this group could become a lasting headache for the party—blunting the advantage it expects from the current of young Latinos steadily entering the electorate.) Second: Shor (along with many Republicans) says that Trump was helped by Latino backlash against last year’s racial-justice protests and calls to defund the police. “The riots and the looting over the summer backfired on the Democrats,” says Jim McLaughlin, a Republican pollster who worked for the Trump campaign and has polled extensively among Latinos. Many Democrats have pushed back on this argument, saying it overstates the protests’ role in driving voters’ decisions and that signs of Trump’s improvement were evident before the demonstrations began.

Yet whatever the immediate role of the protests, a significant share of Latinos—especially men—do express conservative views on a number of racial and cultural flashpoints that align with Trump’s polarizing messaging, according to previously unpublished polling results provided to me by the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute. Most tellingly, roughly two in five Latino men, and one in three Latino women, say police killings of unarmed black men are isolated incidents, not part of a pattern—a view that’s common among Republicans but overwhelmingly rejected among Black people and white liberals.

Among both Latino men and women, about two in five reject the idea that slavery and discrimination have made it hard for African Americans to succeed, and similar numbers agree that discrimination against white people is now as big a problem as discrimination against minorities. In the exit polls, nearly half of Latino voters expressed an unfavorable opinion of Black Lives Matter, an even more negative balance than among white people, according to Edison’s results.

Overall, Trump’s success highlights the persistence of anti-Black racism in a portion of the Latino community, Gallego told me. “There are a lot of good Black-brown coalitions all over the country, but where there haven’t been, Trump and the Republicans exploited the fact … that there is an undercurrent of racism in the Latino community toward African Americans,” he said. “And it’s incumbent on Democrats and Latino leaders to push back on that.”

On immigration, the election underscored that Latinos are hardly of one mind. Even some of those who take liberal positions on the issue simply don’t prioritize it that much. And the PRRI poll found between roughly one-fourth and two-fifths of Latinos expressing conservative views on Trump’s border wall, legal status for the Dreamers, the acceptance of refugees, and immigrants’ relationship to crime, among other issues. These voters often “waited on line, sometimes 10-plus years, to become an American, so being an American is very important to them,” McLaughlin told me. “They don’t want open borders. They don’t want the problems in places that are going on in Mexico and Central America to be happening here in the United States.”

But even those views are not new in the Latino community, so they don’t entirely explain Trump’s advances either. Many conservative Latinos didn’t vote for Trump, or other Republicans, in the past, Odio says. Yet in 2020, “they felt permission to do so.” The key question, he adds, “is what constrained them before, and what freed them up now?” Since the November election, Democratic groups have already devoted significant time and effort to exploring that question. It’s likely that, between now and November 2024, they will spend substantially more.

Trump’s sustained organizational pursuit of right-leaning Latinos likely provides part of the answer to Odio’s query. Two other factors might explain even more, and each offers a reason for Democrats to be optimistic that Biden could recover at least some of the ground lost with Latinos in 2020.

The first is that across both parties, many analysts I’ve spoken with believe that the single most important reason for Trump’s Latino gains was greater trust in him than in Biden to manage the economy, particularly amid the pandemic. Compared to 2016, Trump last year dialed down his anti-immigrant rhetoric and focused much more on promising economic recovery. Many observers on both sides believe that even as the Latino community was disproportionately dying from COVID-19, Trump benefited from this single-minded insistence on reopening the economy.

While much of Trump’s rhetoric downplaying the virus was clearly unrealistic and irresponsible, Democrats “doubled down on the pessimism associated with the virus, and I think that was a major turnoff for a lot of Latino communities,” Curbelo told me. For many Latinos, he said, the “Democratic messaging was all about death and despair, and how much longer this was going to be, and how kids couldn’t go to school and people couldn’t work—and if you are a fairly recently arrived immigrant, that is just the last thing you want to hear.”

From his vantage point in Texas, where he led a major grassroots-organizing effort around state legislative races in 2020, O’Rourke saw the same dynamic. “Trump was able to seize on this false choice of: Do you want to be locked down and have to wear a face mask and not have a job, or have a job?” he told me. Trump’s message, he said, came through as “Fuck the scientists … I’m for jobs.”

But while Trump benefited from a promise to reopen the economy, Biden, if he runs for reelection, will almost certainly be able to say that he actually did reopen it—and, moreover, that the economy is stronger than when he took office. That means the economic tailwind that lifted Trump last time could shift in Biden’s direction in 2024.

A similar dynamic would apply to the final explanation for Trump’s gains: Incumbency really matters in the Latino community. Since 1980, almost every incumbent president won a higher share of the vote among Latinos in their reelection campaign than they did in their first race. (The sole exception was George H. W. Bush, whose vote share fell when he sought reelection in a three-way race during the economic downturn of 1992.) Compared to the other incumbent presidents, Trump’s gains from 2016 to 2020 were about average or a little better than average, depending on which data source you use. But either way, they were far from the most impressive. “Latinos will always vote for an incumbent at a higher rate than they did last time,” Gallego said—a tendency driven by some combination of “respect for authority, a certain level of patriotism, too, [and a belief that] we don’t want to change ships in the middle of a crisis.” If Biden runs again in 2024, that same inclination could help him.

Because of these two factors, virtually every Democratic officeholder or operative I spoke with expects Biden to increase his share of the Latino vote if he runs again. With unified control of government, Amandi said, Democrats have an opportunity to make progress on what he calls the “holy trinity” of Latino priorities: jobs, health care, and education—all of which Biden is stressing in his early agenda. Democrats can “make the case that not only is the [Republican] side [full of] white-supremacist racists who have abandoned democracy, but Democrats are the ones objectively making their lives better here,” Amandi told me.

Yet even if Biden runs better with Latinos in a possible reelection campaign, that wouldn’t answer the big question of whether Republicans are positioned to improve their baseline with these voters over the long term. Given the share of Latinos who express conservative views on many cultural issues, McLaughlin thinks the party is settling if it’s satisfied with the roughly one-third of Latinos that Trump won. Republicans, he said, are “doing handstands because we got one-third of the Latino vote? If I’m the Republicans … I want to win a majority of Latino voters.”

Curbelo also thinks that’s achievable. Privately, some operatives in both parties believe that Trump’s improvement among Latinos means he achieved the best of both worlds in Republican messaging: He fired up white turnout with racist, nativist rhetoric but didn’t pay any apparent price in lost support among Latinos. Still, Curbelo said, Republicans are leaving plenty of right-leaning Latino voters on the table by stamping the party as hostile to immigrants. “There are a number of issues that [would] draw them to the Republican Party, but for most of them they can’t just get there because of the idea that the party is nativist, that the party looks down upon people who look differently and speak differently,” Curbelo told me. “Your growth is always going to be limited if there is this perception that you have some kind of prejudice against certain kinds of people.”

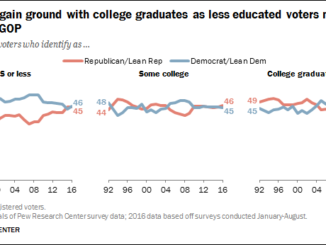

Moving forward, the stakes in this partisan competition are enormous. Latino turnout surged last year: UCLA projects that 16.6 million Latinos voted in 2020, up from roughly 12.7 million in 2016; by its count, the number of Latino voters increased more in that one election than they did between 2008 and 2016. While some Democrats believe this calculation is slightly overstated, it’s clear that Latinos constitute the largest potential source of growth for each party’s coalition. Especially since 2016, Republicans have relied ever more heavily on groups that are shrinking in society, particularly white voters without a college degree. As Curbelo told me, that strategy can win the Electoral College if all the stars align, but it has only generated 45 to 47 percent of the popular vote in the past four presidential elections. Conversely, some Democratic analysts I’ve spoken with argue that the party must regain any lost ground with Latinos because it can’t count on college-educated white suburbanites in elections going forward—Trump was uniquely repellent to many of those voters, especially women.

Latinos will be entering the electorate in huge numbers for the foreseeable future: Mark Hugo Lopez, the Pew Research Center’s director of race and ethnicity research, forecasts that about 1 million U.S.-born Latinos will turn 18 each year through 2027. That number will shrink only slightly through the early 2030s, to a little under 950,000 people annually. The nonpartisan States of Change project anticipates that Latinos will grow from about one in seven eligible voters today to nearly one in five by the middle of the next decade. Odio told me if Democrats can maintain the roughly two-to-one advantage they have traditionally enjoyed among Latinos, most in the party would probably be satisfied. But both he and Valencia argue it’s a mistake to assume that no Republican could do better than Trump, particularly if they sanded down some of the roughest edges of his approach on immigration.

Trump’s unexpected improvement underscores the fluidity of this massive and growing, but diverse and differentiated, community. If nothing else, the 2020 election ought to have dispelled both parties’ tendency to view a constituency this big as a monolith. “We slice white voters to tiny little slivers, and we don’t do the same with Latino voters,” UCLA’s Dominguez-Villegas said. In future elections, both sides will likely increase their focus on better understanding the crosscurrents and fissures of a huge voting bloc whose political loyalties appear much more unsettled than they did even a few years ago. “Latinos did themselves a great service in this election because they are making themselves into a real swing group,” McLaughlin, the Republican pollster, said. “You have to pay attention to them, and you need to go and ask for their votes.”

.