States serving the most preschoolers, such as California, Florida and Texas, don’t meet more than four benchmarks.

by Linda Jacobson

This article was originally published at The 74.

Enrollment growth in state preschool programs was already slowing down before COVID-19. But with thousands of parents skipping pre-K this year, the pandemic has “imposed huge setbacks” that could lead to financial shortfalls, according to this year’s State of Preschool Yearbook, released Monday.

Many children who did enroll have attended remotely for much of the year and may have not received any live instruction from their teachers, said the report, published annually by the National Institute for Early Education Research at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

And because of the pandemic, several states have waived or modified requirements regarding classroom observations, child screenings or assessments, teacher qualifications, even background checks — further contributing to what the institute describes as uneven quality across states.

“Some states have made no progress in 20 years, and other states have risen to become national leaders,” Steve Barnett, senior co-director of the institute, said on a call with reporters.

This year’s report follows the institute’s efforts since last summer to monitor the impact of the pandemic on early-childhood education. In February, the organization released parent survey data showing that enrollment in preschool programs dropped by almost a quarter compared to fall 2019. Parents are also reading less to their children, the survey showed. The yearbook, however, also comes amid expectations that President Joe Biden will soon unveil details of his plan to fund universal pre-K, as he promised during the campaign. Some states and districts are setting aside federal relief dollars for pre-K this fall. But experts note that any efforts to scale up access should include attention to improving classroom quality.

The annual report tracks enrollment, state spending and quality in public pre-K. For the first time, Hawaii and Missouri joined four other states with programs that meet all 10 of the institute’s quality benchmarks, which include having lead teachers with a bachelor’s degree, a strong curriculum and health screenings for children.

But states serving the most preschoolers, such as California, Florida and Texas, don’t meet more than four benchmarks. The researchers estimate it would cost $12 billion to improve the quality of existing state pre-K and Head Start programs and another $62 billion to cover high-quality programs for all 3- and 4-year-olds.

Participation across all public pre-K programs in 44 states and the District of Columbia grew by 12,000 in the 2019-20 school year, to more than 1.6 million — an increase of less than 1 percent over the previous year. But that’s significantly less than the 4 percent growth the year before.

Gaps in funding, teacher pay

States spend on average $5.496 per preschooler, which, adjusted for inflation, was a $141 increase over the previous year. But the researchers estimate that states spend far less than it takes to provide a high-quality program.

That’s one issue that North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper is hoping to address with a proposal to spend $50 million over the next two years for a 16 percent increase in pre-K per-pupil funding. The state currently spends $5,355 per child, leaving districts to make up the difference in salary costs and nonprofit programs to pay teachers thousands less than their counterparts in public schools.

In addition, Cooper’s plan includes more than $9 million toward salary parity for licensed teachers in community-based centers, which can keep teachers from leaving for higher-paying school jobs.

“Continuity of relationships between teachers and children is so important,” Dan Wuori, senior director of early learning at the Hunt Institute, said in an interview. “Helping to bring some pay parity can make it attractive to work in any North Carolina pre-K setting, public or private.”

The institute’s report notes that even if states protect pre-K funding this fall — regardless of the current year’s enrollment decline — cuts in future years are still possible. And some states, including Utah, Virginia and Nevada, are spending less on early-childhood education this school year than originally budgeted. In March, the institute estimated that the financial impact of the pandemic could match that of the Great Recession, when enrollment growth slowed and 21 states cut per-child spending.

With Biden in office, early education advocates are eyeing a much larger federal role in expanding access to pre-K. On April 9, he previewed his federal 2022 budget priorities, including more than doubling spending for Title I. During the campaign, he promised to triple funding for the program, which supports high-poverty schools, to extend preschool to all 3- and 4-year-olds.

In recent years, several cities have moved ahead of their states in expanding local programs, paying for them with a variety of revenue sources, such as a soda tax in Philadelphia and a sales tax in San Antonio. And last week, Los Angeles Unified School District board members announced plans to use federal relief dollars to expand preschool this fall and push for universal access by 2024.

The relief package “is a game changer if you use it for the foundation for a plan to move forward,” Barnett said during the media call, but added, “making long-term commitments based on short-term resources Is not a smart idea.”

Lessons from New York

Rapidly expanding the number of classrooms can compromise quality, according to a recent study of the New York City Department of Education’s pre-K program.

The research shows that as Mayor Bill de Blasio continues to ramp up services for 3-year-olds, centers that enroll larger shares of white and Asian children meet higher quality standards than those serving more Black and Hispanic children. The report, however, notes as a positive sign the district’s move in January to focus pre-K expansion in communities hardest hit by the pandemic.

The findings have implications for Biden’s push for universal pre-K, said author Bruce Fuller, an education and sociology researcher at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The clear lesson from the Big Apple is that big entitlements must be managed carefully, tilting quality gains fairly toward low-income families,” Fuller said. “Otherwise, as our findings reveal, better-off families win higher quality pre-K.”

In response, Sarah Cassanova, a spokeswoman for New York City schools, said the Berkeley study “only considers one narrow measure of quality” and that the city’s programs continue to “make important gains in both quality and equity.” The department, she said, is “committed to understanding and addressing any disparities in access to high-quality early education, particularly as our city recovers from the pandemic that has disproportionately impacted communities of color.”

Sharp enrollment declines

The institute’s data on pre-K enrollment this year shows the most dramatic declines in participation among children in poverty. Only 13 percent of preschoolers were attending an in-person program, according to the parent survey. Overall enrollment rates in center-based programs have dropped by almost a quarter since the start of this school year — a decrease from 71 to 54 percent for 4-year-olds and from 51 to 39 percent for 3-year-olds.

After kindergarten enrollment plummeted last fall, district leaders expect to see an increase next school year in overage kindergartners as well as 5-year-olds who have not had a typical early-childhood experience. In addition, the institute’s survey showed a decline in parents reading to their children at least three times per week and practicing numbers, words and letters — activities that help children make the transition to a more formal curriculum. But they increased the time spent telling stories and singing songs.

Hawaii is offering a summer program for children who skipped pre-K this year, and in a recent Hunt Institute webinar, New Mexico Secretary of Education Ryan Stewart said his state plans to use relief funds to offer a summer transition program.

“I worry the most about early numeracy work,” he said. “Families still have books and reading opportunities, but it’s harder to create those natural ways [to introduce] number concepts.”

Parent Michelle Galindo of San Diego opted to keep 3-year-old Roberto out of virtual public preschool this year but might send him to transitional kindergarten in the fall if it’s in person and not so “limited and structured.”

“My priority is for him to experience hands-on learning, to be able to share and collaborate and cooperate,” she said. “Why else enroll him in preschool?”

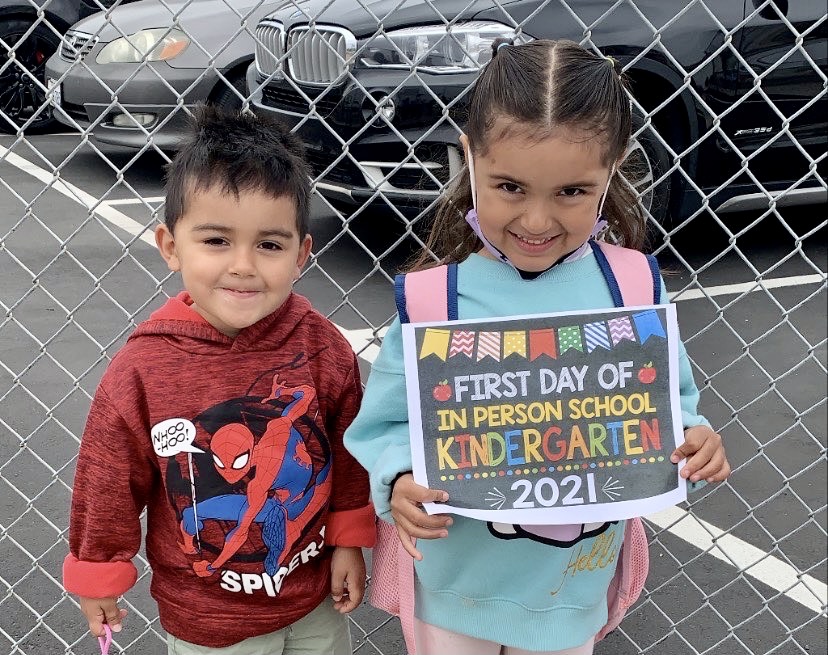

Cecilia Santiago-Gonzalez, another California parent, enrolled 4-year-old Camila in the Azusa Unified School District’s virtual pre-K program last fall but sometimes wondered if the daily Zoom sessions were worth the effort, since she was also working at home and caring for a 1-year-old.

“Asking a 4-year-old to be still and pay attention and to remain engaged is a big task,” she said, adding that she signed her daughter up for a soccer league so she could interact with other children.

Other parents have had a more positive experience with remote programs. In Philadelphia, Maritza Guridy said her 5-year-old son, Tarrell, and her 4-year-old foster daughter, Ja’Ziyah, “are more than ready for kindergarten” and have adjusted well to Google classroom. “They know how to put themselves on mute. They know how to share the screen.”

Still, as soon as the district started its hybrid schedule March 8, she jumped at the chance to send the children to school twice a week.

With Black and Hispanic communities hit hardest by the pandemic and experiencing more financial stress than white families, experts say teachers will likely need to spend more time than usual on children’s social and emotional adjustment as well their academic skills.

Albert Wat, senior policy director at the Alliance for Early Success, noted during the Hunt Institute webinar that Black children, especially boys, were already being suspended and expelled in the early grades at much higher rates than white children before the pandemic.

“If all the focus is on catching up kids with academics,” he said, “we’re going to lose more of those kids.”

Linda Jacobson is a senior writer at The 74.