The undocumented population today—mostly Latino and overwhelmingly people of color— have none of the privileges accorded to previous generations of white immigrants.

by

As we view images of families and unaccompanied children attempting to flee violence in their home countries for a better life here, one cannot help but wonder if they weren’t from Latin America but were white immigrants from Europe, would they be treated differently.

Examining immigration policy through a systemic racism lens reveals that today’s largely Latino undocumented immigrants face far harsher consequences than white Europeans of years past for the same exact offense of unauthorized entry. A system that treats immigrants differently solely to their race is essentially the textbook definition of structural racism.

“Illegal” immigration was remarkably common in past decades. Around the turn of the century many Europeans came to the US “with a tag on,” a label sewn into their clothing to allow an employer or labor contractor who had paid for the immigrant’s passage to find the newcomer at the dock on Ellis Island. While illegal—indentured servitude having long been outlawed[ii]–the practice was so widespread that one labor union official testified in 1912 that “more than 8 in 10” of the million immigrants who had entered that year had a job waiting from an employer that paid for the newcomer’s passage.[iii] Others came as illegal stowaways aboard ships or unlawfully crossed the border from Canada, as CBS Evening News Anchor Nora O’Donnell recently discovered her Irish grandfather had done in 1924.[iv]

Others used any means necessary to escape persecution. Fleeing a pogrom in Russia, composer Irving Berlin’s family used false passports to enter the US in the late 1800s.[v] Harvard Law professor Alan Dershowitz’s great-grandfather created fraudulent jobs at a synagogue he’d started to facilitate his relatives’ entry to the U.S. on the eve of the Holocaust.[vi] Jared Kushner’s forebears crossed multiple European borders illegally, falsely listed a sponsor in the US, used an assumed name, and lied about their country of origin in order to enter the US in the 1930s.

In sharp contrast to today’s undocumented population, “illegal” European immigrants faced few repercussions. There was virtually no immigration enforcement infrastructure. If caught, few faced deportation. All of those who entered unlawfully before the 1940s were protected from deportation by statutes of limitations, and in the 1930s and 1940s, tens of thousands of unauthorized immigrants like Nora O’Donnell’s grandfather were given amnesty.[vii] The few not covered by a statute of limitations or amnesty had another protection: until 1976 the government rarely deported parents of US citizens.[viii] There were no immigrant restrictions on public benefits until the 1970s, and it wasn’t until 1986 that it became unlawful to hire an undocumented immigrant.

In sum, from the early 1900s through the 1960s, millions of predominantly white immigrants entered the country unlawfully, but faced virtually no threat of apprehension or deportation. Businesses lawfully employed these immigrants, who were eligible for public benefits when they fell on hard times.

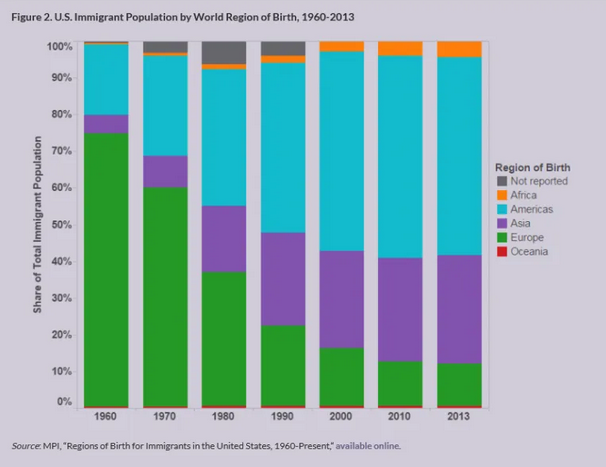

By contrast, the undocumented population today—mostly Latino and overwhelmingly people of color— have none of the privileges accorded to previous generations of white immigrants. The toughening of immigration laws coincided with a shift of immigration from Europe to newcomers from Latin America, Asia, and Africa, often in the context of racialized debates targeted mainly at Latinos. Researchers have documented how through the 1960s, racialized views of Mexicans shaped law and bureaucratic practice.[ix] Over the next decade, Congress ended the Bracero program, which had allowed as many as 800,000 temporary migrants from Mexico annually to work mainly in agriculture; cut legal immigration from Mexico by 50%; and ended the long-standing practice that parents of US citizens wouldn’t be deported. Reducing lawful means of immigrating predictably led to a rise in unauthorized entries, which was met with calls for tougher enforcement.[x]

Restrictions on access to public benefits came next. Amidst a highly racialized debate, in 1971 then-Governor Reagan pushed through a sweeping California welfare reform plan that denied benefits to unauthorized immigrants. Other states and the federal government soon followed suit.[xi] In 1996, after a deeply racialized debate over California Proposition 187, which sought to deny state services to undocumented immigrants, Congress went even further to restrict legal immigrants from most federal benefits, although some have since been restored. That year Congress enacted the provisions that prevent most Latinos crossing the Southern border from receiving green cards.[xii] The same bill empowers state-local police—such as the infamous Joe Arpiao, who was convicted of racial profiling of Latinos on the mere suspicion that they might be undocumented—to enforce immigration laws.

Thus, today’s undocumented immigrants of color face far harsher consequences for their offenses than their white predecessors. First, they’re much more likely to be apprehended. Over the past half-century, the immigrant enforcement system has grown from just a few hundred border guards to what the Migration Policy Institute calls a “formidable machinery” larger than all other federal law enforcement agencies combined,[xiii] further augmented by state and local police agencies.

Once apprehended, there is no statute of limitations for unlawful status. The law bars mainly Latino border crossers from adjusting to legal status, but permits predominantly non-Hispanic visa overstayers to receive permanent residence—despite the fact that over the past decade, visa-overstayers outnumbered illegal border crossers by a 2-1 margin. Unsurprisingly, even though about 57% of immigrants are Hispanic, consistently well over 90% of those deported are Latino.[xiv]

Because employers cannot lawfully hire the undocumented, most are relegated to the underground economy, often in jobs that the Trump administration ironically declared were “essential” during the pandemic. If they lose their job or fall ill, they’re ineligible for virtually all public benefits, even though they pay taxes into the system.

Unlike prior generations of undocumented immigrants, the punitive immigrant policies of today has implications for the families of “illegal aliens,” including an estimated six million of their US citizen or lawfully present family members. They not only live every day under the threat of family separation via deportation, but are largely denied public benefits, extending the negative implications of the structural racism present in the immigration system.

President Trump used openly racialized appeals to justify anti-immigrant policies, but he needn’t have, since our immigration system embodies the assumption that today’s immigrants of color are undeserving of the privileges afforded to previous generations of white European immigrants. By legalizing the status of undocumented immigrants whose only offense is doing exactly what their white counterparts did generations ago, the Biden Administration’s immigration plan would help reverse this racial inequity. Biden’s plan allows undocumented immigrants already living in the United States and who have committed no other serious offenses to apply for legal status. This would not only help the economy recover–according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, similar legislation would reduce the budget deficit by $1 trillion, increase GDP by 3.3%, and increase wages for all Americans after 10 years–but will simultaneously address structural racism within our immigration system. All Americans seeking a rapid economic recovery and a more racially just society should support it.

Charles Kamasaki, Senior Advisor at Unidos US and Fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, is the author of Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die (Mandel Vilar Press, 2019), from which this essay is adapted.

[ii] Joel Millman, The Other Americans, How Immigrants Renew Our Country, Our Economy, and Our Values, Viking, 1997, p. 62.

[iii] Statement of Rev. M.D. Lichliter, “The Further Restriction of Immigration,” House Hearings, Committee on Immigration & Naturalization, February 9, 1912, part 4, p. 19, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Relative_to_the_Further_Restriction_of_I/JUwLAAAAYAAJ.

[iv] “Coming to America,” Finding Your Roots, Public Broadcasting Service, Episode 6-16, first aired January 12, 2021.

[v] Aviva Chomsky, Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal (Beacon Press 2014).

[vi] “Our People, Our Traditions,” Finding Your Roots, Public Broadcasting Service, Episode 2-07, first aired November 4, 2014.

[vii] Mae M. Ngai, “How grandma got legal,” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 2006, and Mae M. Ngai, “Second Class Noncitizens,” New York Times, January 30, 2014.

[viii] Aristide Zolberg, A Nation By Design, Harvard University Press, 2008.

[ix] Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, Princeton University Press, 2003.

[x] Charles Kamasaki, Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die, Mandel Vilar Press, 2019.

[xi] Cybelle Fox, “‘The Line Must Be Drawn Somewhere’: The Rise of Legal Status Restrictions in State Welfare Policy in the 1970s,” Studies in American Political Development, October 2019.

[xii] Charles Kamasaki, Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die, Mandel Vilar Press, 2019.

[xiii] Meissner, et. al., Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery, Migration Policy Institute, 2013.

.