Parents of wealthier kids spend a lot more time in schools. Because those parents often have the means to enroll their children in private schools, and because wealthier students often perform better on standardized tests.

by Asher Lehrer-Small

This article was originally published at The 74.

It’s a foundational premise of the American dream: that through hard work and diligent study, young people can use education to access opportunities that were denied to their parents. However, mounting evidence suggests that segregation — not just by race, but also by income — within the school system may stymie those meritocratic aspirations.

Income-based school segregation has been steadily increasing over the last 30 years, studies show. But while researchers have previously demonstrated that low-income students are increasingly attending different schools than their more affluent peers, a new working paper published by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University finds that income segregation within schools, from classroom to classroom, is also on the rise.

“If we as a country hope to think of our schooling system… as being egalitarian and giving everyone the opportunity to access resources that allow them to live to the fullest potential, then it’s discouraging,” the study’s co-author Dave Marcotte, a professor at American University, told The 74.

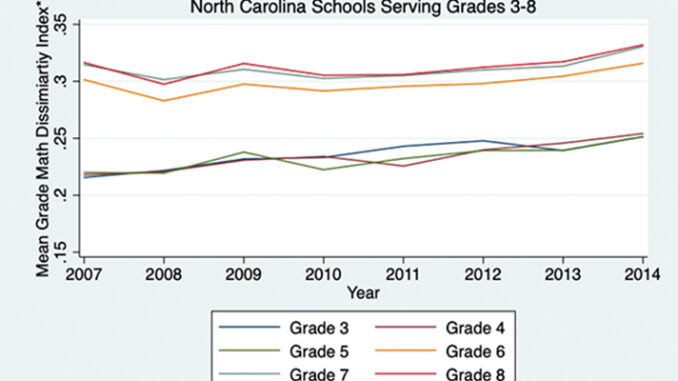

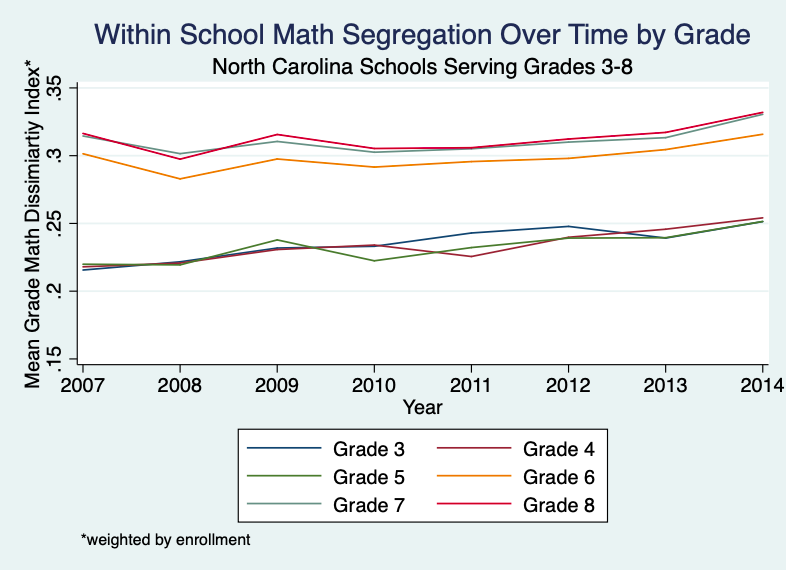

Marcotte and American University Ph.D. student Kari Dalane found that between 2007 and 2014 in North Carolina, where the study focused, segregation within elementary schools rose by about 25 percent. In real terms, they found that at the start of the study, an average class of 20 students would have needed to move four students to another classroom within the school to reach equal levels of wealth dispersion, Marcotte explained. By the end of the study in 2014, that number had risen to five.

The results are not surprising to Richard Kahlenberg, who edited The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform Strategy and has long studied income segregation in schools.

“People are familiar with the idea of school segregation at the building level, but then we often see even within integrated school buildings, resegregation at the classroom level,” said Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation. “Low income students, disproportionately students of color, end up in remedial or basic classes.”

The trends identified by the American University team held true even while controlling for students’ racial identity. In fact, over the course of the study, racial segregation between schools did not increase, while income-based segregation did, according to the paper.

The explanations for the trend toward classrooms sorted by income are not fully clear. Still, the authors do hold some hypotheses.

“Parents of wealthier kids spend a lot more time in schools,” said Marcotte. Because those parents often have the means to enroll their children in private schools, and because wealthier students often perform better on standardized tests, they can exert disproportionate levels of pressure on school decisionmakers.

“Principals may be offering schools within schools, or tracking mechanisms to keep certain parents happy,” he explained. The end result? “Wealthier kids can sit with other kids like them.”

Still, the findings of the study also ring some encouraging notes. Past research has described eliminating racial segregation as a game of whack-a-mole: when officials think they have mitigated it in one place, it pops back up in another. Districts that have low levels of racial segregation tend to have high levels of racial segregation hidden within schools, and vice versa.

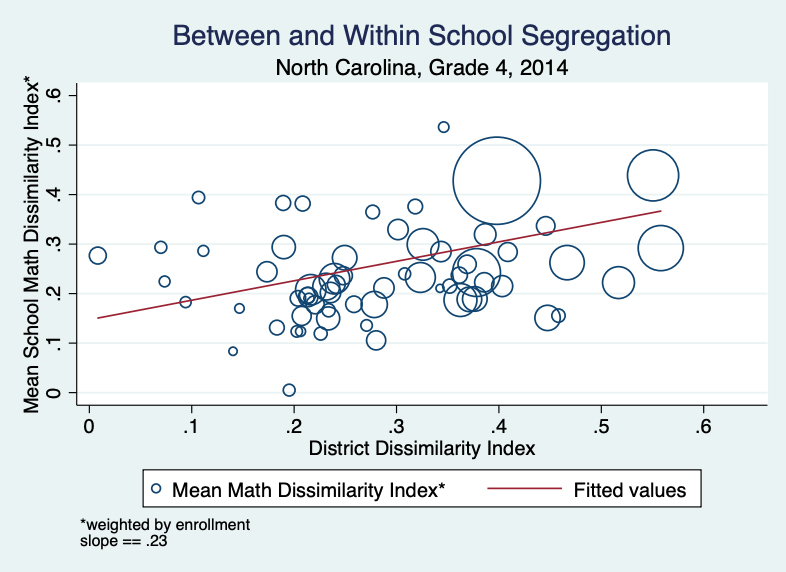

Marcotte and Dalane’s study, however, finds income-based segregation within schools to have a positive relationship with income-based segregation between schools. In other words, districts with imbalances in wealth from school to school also tended to have buildings with more skewed levels of wealth from classroom to classroom.

But while the prospect of double-segregation might raise eyebrows, the flip side of that trend gives the Century Foundation fellow optimism. He sees good news in the fact that districts with more integrated schools also tended to have schools with more integrated classrooms.

“One of the common arguments against integrating schools by income is that you just end up inevitably resegregating at the classroom level, so why bother? And in fact, in North Carolina, at least, according to this research it appears that school districts that are more committed to school-level income integration also appear to have a commitment to classroom-level income integration,” Kahlenberg said.

“It’s not inevitable that when we take affirmative measures to integrate by income, that schools will invariably resegregate at the classroom level, quite the opposite in this study.”

Of course, identifying trends in income segregation is one thing. Achieving integrated schools and classrooms is quite another.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” said Marcotte.

Kahlenberg, however, has a few ideas for where to start. “We need new tools to address economic housing segregation,” he said.

Even after striking down unconstitutional zoning laws that excluded residents by race, the U.S. has not removed zoning laws that discriminate by wealth. “Very commonly, we have communities that are engaged in exclusionary zoning, where they say, ‘You can only live here if you have the money to buy a single-family home. If you can only afford a duplex or a triplex, we don’t want you,’” explained Kahlenberg.

Despite such structural factors hindering economic integration, he points to examples such as Stamford, Connecticut, where intense efforts have gone into reducing tracking along lines of socioeconomic status, as exemplars for proactively integrating classrooms.

“There’s an aggressive effort to make sure that disadvantaged students who would do well in advanced courses are made aware of the opportunities and encouraged to participate,” said Kahlenberg.

Asher Lehrer-Small is an Editorial Fellow at The 74.