At some higher education institutions, the plunges are almost beyond comprehension. These setbacks for low-income/minority students are especially painful in light of the tenuous progress those same students had been making in recent years.

by Richard Whitmire

This article was originally published at The 74.

When families huddle in the cold outside nursing home windows, you can see a COVID-19 tragedy unfolding. But a less visible pandemic tragedy is just now coming into view: college dreams for low-income students going up in smoke.

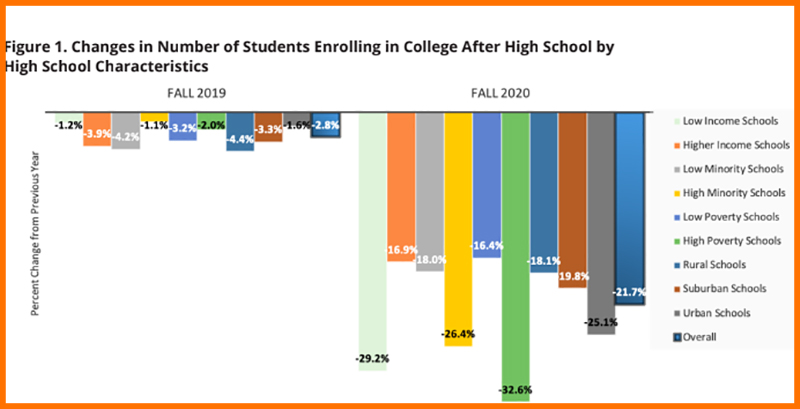

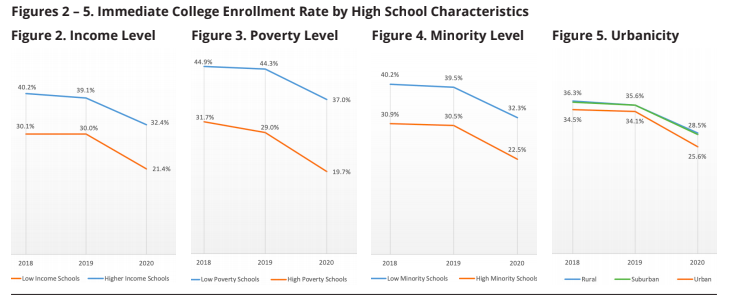

Regardless of the type of college — community college, public colleges or private — fall of 2020 enrollment rates for low-income students plunged at rates nearly double that for students from higher-income high schools, reports the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Across all types of colleges, enrollment for low-income high school graduates declined by 29.2 percent, compared to a 16.9 percent drop for their counterparts from higher-income high schools. At community colleges, the drop for low-income students was even more dramatic — 37.1 percent. This is the first time the Clearinghouse, the nation’s best source for tracking college attainment data, has traced the impact of COVID-19. Using the 2020 high school graduate data from more than 2,300 high schools broken out by income level, poverty, race and urban, suburban or rural locale, the Clearinghouse was able to analyze college enrollment gaps by demographic and economic background.

These divides between rich and poor may grow. The Clearinghouse figures released Thursday show a troubling 22 percent drop for all 2019 high school graduates, but much of the decrease among higher-income students may be due to them taking “gap years” before college in the hope of being able to fully enjoy campus life with in-person classes. They are highly likely to return. The lower income students may tell themselves they’re taking a gap year, but educators say they are far less likely to enroll.

“What does this mean? It means a less qualified workforce, a less skilled workforce, a less productive workforce for the entire economy,” Doug Shapiro, executive director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, told The 74. “It means less economic and income opportunity, and mobility, for our most disadvantaged students. There are so many implications.”

At some higher education institutions, the plunges are almost beyond comprehension. At Southwest Tennessee Community College in Memphis, half the Black male students enrolled in the spring of 2020 and still working toward graduation failed to enroll this fall — 830 men.

These setbacks for low-income/minority students are especially painful in light of the tenuous progress those same students had been making in recent years, gains that I laid out in a recent book, The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.

Those gains in college graduation rates came from three separate sources: Philanthropies stepping up to dramatically boost the amount and quality of college advising for low-income students, colleges getting a lot smarter about how to keep their more fragile students on track for graduation, and the top charter school networks pioneering replicable pathways to boost college graduation rates for low-income students by two to four times the national average for similar students.

The Clearinghouse data just released shows all this in jeopardy.

The community college declines are both surprising and dismaying. In the early stages of the pandemic, when it was clear that many students were hesitating to return or enroll in costly four-year colleges going online, many education experts predicted that community colleges would absorb those students.

But just the opposite happened. Shapiro says there are two reasons behind that. Four-year colleges worried about enrollment plunges got aggressive about recruiting and offering aid. “They were more concerned about the enrollment and the revenue they depend on.” Plus, two-year colleges proved to be less adept in shifting to online learning, in part because their students are less likely to have access to essential technology.

Where are these students going? College officials are scrambling to find out. At Southwest Tennessee Community College, a team is contacting every student who failed to return, both to discover why and to entice them back with added supports.

Citing anecdotal evidence, community college leaders say many of these aspiring college students took full-time jobs to support their families. Others got sidetracked because they lost contact with their high school counselors when K-12 schools abruptly shut down last spring. Also cited: Low-income students are less likely to fare well with online courses. They lack sophisticated computer equipment and reliable broadband and are more likely to need hands-on help from instructors.

The overall reason can be summed up this way: Low-income students are more fragile students across the board, and therefore more likely to step away from college plans.

It is tempting to conjecture that what’s happening affects only one class of high school seniors and college underclassmen. But that would be naive. All evidence to date points to pandemic effects reaching into the youngest grades, with fewer Black students returning to classroom learning, even when schools are open. The students struggling with remote learning are most likely to be low-income. And while the philanthropy-driven college guidance efforts quickly ramped up their online work, there’s no expectation that will replace in-person guidance.

Next year, if the pandemic ends and the higher-income students on gap years return to campus, there’s every reason to believe the race and income divides will grow. “That’s absolutely right,” said Shapiro. “The gaps are likely to worsen. Gap years are something higher-income students are taking by choice. These (lower-income) students are entering the workforce to support families, and they are getting further and further away from post-secondary pathways.”

Wil Del Pilar, vice president of higher education at The Education Trust, points out another impact. First-generation college-goers often act as guides for family members behind them in age. “If you are losing a generation, that threatens another generation of young students who found the way paved for them by family members who helped navigate the process. This is a threat to social mobility, to relegate those in the lowest incomes to those incomes forever.”

And this could also change the face of colleges, he said. “This is going to further segregate them and make them what they were originally: havens for the wealthy.”

What this means is that the American Dream for many low-income students has been deferred, perhaps permanently. Young people not born to well-off families will not surpass their parents in income and home ownership, they will not surge into promising careers, and they will not trust the American system to do right by them.

This tragedy is not as visible as families hovering outside nursing homes. But it’s every bit as real.

Richard Whitmire is the author of several books, most recently “The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America.” Whitmire is a member of the Journalism Advisory Board of The 74.