by

With the new school year now upon us, questions of how to reopen safely are paramount. The nationwide spike in COVID-19 cases over the summer has forced many school districts to reverse their opening plans, either by delaying the start of the academic year or by switching to remote-only instruction for the initial part of the school year. Given the struggles to keep students engaged with learning when schools shut down in the spring, eventually opening for live instruction is seen as a necessary step to prevent further learning losses. The most vulnerable students—those in poverty or from communities of color—were the hardest to reach during shutdowns and will be further set back if they cannot safely access their classrooms in the new school year.

To lower the risk of subsequent outbreaks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends schools implement several practices, from requiring educators to wear masks to ensuring social distancing, and frequently sanitizing bathrooms and high-touch surfaces in the classroom. Schools also need to assess the safety of their school facilities, including ventilation systems to ensure clean air in classrooms, though these considerations have received less attention in ongoing conversations about reopening schools.

In this post, we describe how the safety and adequacy of learning spaces are another aspect of school inequalities, which can have implications for students’ access to live instruction during the pandemic. We offer three recommendations for policymakers and school leaders that can help reverse patterns of environmental racism.

Inequalities in school facilities amid the pandemic

Existing evidence on coronavirus transmission indicates a lower risk of spread outdoors because social distancing is easier to maintain and virus particles are dispersed by the wind. Conversely, spending lots of time in indoor spaces with poor ventilation systems present a high risk of transmission. Though the CDC guidelines for reopening schools do not recommend facilities upgrades to ensure air quality inside classrooms, CDC recommends office buildings maintain or upgrade ventilation systems before reopening. Health experts, along with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),have advised improving schools’ air filtration and ventilation before welcoming students back.

Unfortunately, many American schools have ventilation systems that are inadequate and could pose a vulnerability in reopening amidst the pandemic. A recent report from the Government Accountability Office estimates that 36,000 schools nationwide need to update or replace heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

The report further documents how the need for investments in school facilities are unequally distributed, with the greatest need for improvements in schools serving high shares of students in poverty, which, in turn, are often located in communities of color. Funding for schools’ facilities primarily come from local sources, the leading explanation for why we observe greater needs among disadvantaged schools.

Inadequate learning environments linked to lower student outcomes

We have known about the sorry state of school facilities for years. In 2017, the American Society of Civil Engineers graded Americas’ school infrastructure a D+. A 2014 report from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) concluded that 53% of public schools needed to spend money on repairs and renovations to bring facilities into good overall condition; the total estimated for required upgrades was approximately $197 billion (about $4.5 million per school needing work). Teachers, first-hand witnesses of poor facilities along with students, have also been advocating for resources to improve school facilities: In 2016, the American Federation of Teachers and its local affiliate sued Detroit Public Schools after an inspection report revealed that all schools had at least one safety violation.

Not only are poor learning environments unbearable, but they have also been shown to adversely impact student outcomes in several empirical studies. For example, results show various aspects of the school learning environment—including those inside the school building (air filters in Los Angeles county), on school properties (school bus exhaust systems in Georgia), and in the immediate vicinity around schools (locations near superfund sites nationwide)—have all been linked with lower test scores and student attendance. The link with attendance is a telling piece of the puzzle: It suggests lower health outcomes among students are a likely mechanism for missing out on instruction, which then contributes to lower achievement.

Though inadequate facilities anywhere should be remedied, the burden of these undesirable learning conditions and adverse outcomes disproportionately impact disadvantaged students and students of color, perpetuating longstanding inequalities. Virtually all the studies linked above document larger negative consequences among these communities, which warrant particular attention to the safety of their classrooms.

Schools as an element of environmental racism

Unequal learning environments can be viewed as part of the broader social problem known as environmental racism, where marginalized racial groups suffer from poor environmental conditions in their communities and public spaces. Research dates to the early 1980s when Dr. Robert Bullard, a now-prominent advocate for environmental justice, first documented the “pollution advantage” for white populations in Houston. The study revealed a racial pattern in the city’s waste dumping: 82% of all solid waste disposed from the 1930s to 1978 was dumped in mostly Black neighborhoods–even though Black people made up only 25% of Houston’s population.

In the four decades since, a steady stream of evidence indicates the continuing inequalities in public environments for different racial groups. The Department of Health and Human Services reports that Black people were three times more likely than white people to die from asthma-related causes, with Black children having an asthma death rate seven times higher (as compared to white children).

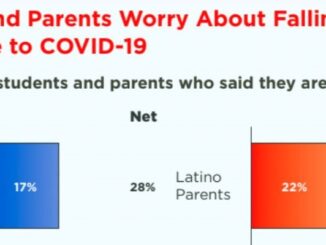

It is these poor environmental conditions and the corresponding poorer health among Black, Latino, and Native American communities that contribute to the unequal impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on these same groups. Rates of infection and case fatality rates are both higher among these communities.

The elevated risks of the pandemic combined with the pre-existing vulnerability of school facilities in nonwhite communities lead us to expect that these communities will have less access to safe learning environments for the duration of the pandemic. Even if all children could return to school, schools in communities of color will be less safe and resilient in the face of the pandemic, and more likely to shut down again as the virus continues to spread. Thus, we expect students of color to spend less time in physical classrooms and more time online, with lower academic progress as a result.

Communities of color need safer learning environments, immediately and permanently

Unfortunately, the long-documented unequal state of the nation’s school infrastructure leaves the most disadvantaged students most vulnerable in the pandemic, and most likely to get cut off from live instruction in the coming school year. We see three potential levers here that we encourage policymakers and school leaders to consider.

- Federal aid to maintain and upgrade school facilities. The 2019 Rebuild America’s Schools Act (H.R. 865) has been touted as part of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s efforts to invest in American infrastructure. Given the dearth of local funding in the most disadvantaged areas and state coffers being hit hard by the pandemic-fueled recession, aid from the federal government is sorely needed to address the inequalities in the adequacy of school facilities.

- Invest in green schools. Green schools are those built to reduce environmental impact and costs, improve health and wellness of occupants, and provide environmental and sustainability education. We suspect green schools will be more resilient amid the pandemic, as the learning environments in them are not only cleaner and more sustainable, but outdoor spaces on their campuses can be readily used as learning spaces to accommodate socially distant learning. And, importantly, a recent study shows that new green schools are disproportionately built in socio-economically disadvantaged communities—an encouraging pattern that runs counter to those documented above.

- Adopt practices to make indoor air safer in schools. Finally, even without federal aid or investments in new green buildings, schools can take steps on their own to make the air in their buildings more conducive to learning. The EPA offers resources to schools helping to improve indoor air quality, including helpful suggestions that even cash-strapped schools can start small and build up over time to make notable improvements.

All schools need resources to deal with the pandemic, though we have paid too little attention to physical facilities and their role in creating safe learning environments. We encourage action to remedy these inequalities quickly, and a dedicated effort to invest in maintaining safe learning spaces—especially for communities of color—into the future.

Alejandro Vazquez-Martinez is a Research Intern in the Brown Center for Education Policy at The Brookings Institution.

Dr. Michael Hansen is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the director of the Brown Center on Education Policy. @DrMikeHansen

Diana Quintero is a Senior Research Analyst within the Brown Center on Education Policy at The Brookings Institution.