Generations of demographic change in Maricopa County and a wave of newly eligible voters have made Arizona a presidential battleground state.

by Jose Del real

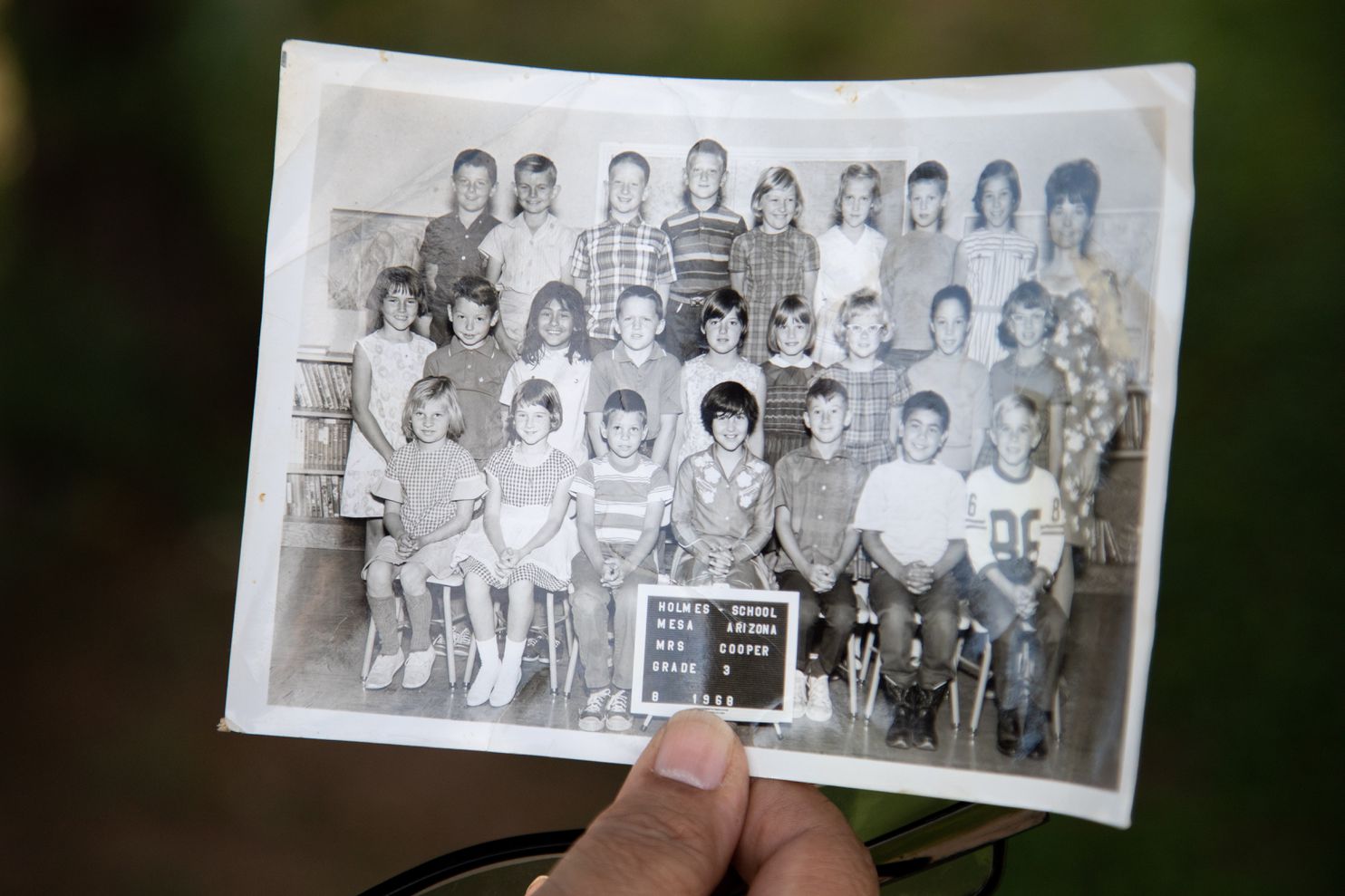

Growing up, Dora Chavez Anaya sometimes felt like the only dark-skinned girl in all of Mesa. As the Mexican American daughter of a copper miner, she recalled, the Anglo children on her block were forbidden by their parents from playing with her. Peers at school sometimes called her the n-word.

She felt powerless. She was powerless.

But from her quaint suburban street in Maricopa County, Ariz., where she has lived all of her 60 years, Chavez has witnessed a dramatic change.

Gone are the desert-defying agricultural fields of the East Salt River Valley, replaced by the boom of housing developments. Gone, too, is her sense of being a lone Latina in a White world. Most of her neighbors today are Mexican Americans like her.

Now, Chavez hopes that the changes will translate to more political power for Arizona Latinos, many of whom have felt alienated by the Republican Party’s rhetoric on racial justice and immigration. Although these voters have historically been written off by national campaign strategists, Democrats increasingly believe they could provide crucial voting margins for Joe Biden in November. A victory in populous Maricopa for the presumptive Democratic nominee would likely mean a statewide victory in Arizona, which in turn could be decisive in a close national election.

Sensing an opportunity, Biden has hired a litany of respected political hands to build what they say will be a competitive campaign in Arizona, part of a broader effort to shore up support in presidential battleground states across the country. A high-profile U.S. Senate race and anger over the Republican Party’s management of the coronavirus pandemic, which has ravaged Arizona and disproportionately affected Latino communities, have given those efforts an additional sense of momentum and urgency.

But longtime organizers in the state remain skeptical that Biden and national Democrats will invest the right resources to court Latinos — a diverse group that includes first-time voters, liberals and also many with socially conservative and moderate inclinations. Meanwhile, Latino Decisions, a prominent polling firm, recently found that Biden is winning among Arizona Latinos but lags in support compared to Hillary Clinton at this point in the 2016 election.

For Chavez, elections are an opportunity to stand up for herself, to show that her opinions matter and people like her have dignity.

But she wonders if other would-be voters see it that way, after disappointment in so many previous elections. Even if Latino voters turn out in large numbers, she worries politicians won’t stay focused on Latino communities’ needs.

And she has heard too many express the belief that their votes will not make a difference.

“We’ve lived in a state where our voice wasn’t going to count for much,” said Chavez, sitting in her home, alone, afraid to go out because of the pandemic. “I would see people complain about how their vote would never make a difference. They’d think, we’re just Brown people, White people make the rules. But I would always vote. It does matter. It does matter.”

Thirty-one percent of Maricopa County residents are Latino, according to census figures.

Since the last presidential election, twice as many voters in the county have registered as Democrats than as Republicans. And there’s the possibility for even more growth for Democrats: An estimated 100,000 Latino voters have come of age since the 2018 midterm elections, said Joseph Garcia, director of public policy for Chicanos Por La Causa, a nonprofit based in Phoenix. He said these voters increasingly lean Democratic.

“Every election cycle I get asked, ‘When are Latinos going to flex their muscle at the ballot box?’ Five years ago there weren’t enough Latinos over the age of 18. The numbers are there now,” Garcia said.

“Maricopa County is the key to winning Arizona, and Arizona may be the key to who wins the election in November,” he added. “If there’s any slippage in the county, Trump’s going to lose the state.”

While the state’s newcomers — professionals lured by the state’s booming economy and low taxes — have received much of the credit for the leftward shift in the state’s politics, it is Latinos who have lived and grew up in Arizona, he said, who are at the heart of the state’s changing political dynamics.

There remain doubts about how committed Democrats will be to sustained outreach. Longtime community organizers in the state say that conventional wisdom about low turnout among Latinos has in some ways become self-fulfilling. Meanwhile, Republican voters, who tend to be older, are more likely to cast ballots.

And hamfisted political messaging does not help.

“Immigration sucks all the oxygen out of the room sometimes. That’s not all that’s important to the Latino community. Education is always number one. People care about jobs, workforce development, health care, affordable housing,” Garcia said.

The Biden campaign, which struggled with fundraising in an usually crowded Democratic primary, is coming to the effort late.

And nearly half of Arizona Latinos, according to a survey of registered Latino voters by Latino Decisions, said they had not been contacted by any campaign yet. This week, the Biden campaign announced it had hired Latino Decisions to consult on its Latino outreach.

John Loredo, the former Democratic leader in the Arizona House of Representatives, contends that Clinton lost the state to Donald Trump by 3.5 percentage points in 2016 because national Democrats did not invest many resources in Arizona until the final sprint in the election. Grassroots Latino organizers used their limited resources to unseat controversial Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, a Republican — which they accomplished even as Trump won the county and the state.

“Where the campaigns focus, where there are financial resources, we’re actually winning elections,” he said.

Latino voters have already been crucial to Democrats, perhaps more than they have been credited. As Democrats seek to replicate the 2018 success of Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), the first Democrat elected to the U.S. Senate from Arizona since the 1980s, many pundits have focused on White voters, who still account for 75 percent of the electorate in Arizona. They have especially targeted conservative-leaning women who may have soured on President Trump.

That misses a big part of the story of Sinema’s victory: The huge support she received from Latinos statewide. Exit polls show they voted for her in larger numbers than they did for the Democratic candidate for governor that year, who ultimately lost to Gov. Doug Ducey (R). Those voters provided an important — and potentially decisive — margin for Sinema in a tight race in which the majority of non-Hispanic White voters cast ballots for McSally.

Mario Diaz, a Democratic consultant based in Phoenix, credited Sinema’s huge fundraising totals and her “very pragmatic political philosophy,” along with her willingness to criticize Democrats and “even complimented the president a few times.” And her message, focused on moderates, spoke to many Latinos.

Republican Martha McSally, who lost to Sinema but was appointed to a vacant U.S. Senate seat by Ducey at the end of 2018, is now running again — this time against Mark Kelly (D), an astronaut and spouse of former congresswoman Gabby Giffords (D). The Kelly campaign has taken particular notice of the large Latino vote Sinema was able to pull together in 2018.

Republicans meanwhile are relying heavily on older, White voters to show up to the polls, and say they intend to invest millions of dollars in advertising and canvassing efforts even during the pandemic.

“Democrats don’t have the turnout machine that Republicans have. From a tactical standpoint, that’s really where Republicans have the advantage,” said Max Fose, an Arizona political consultant and former campaign hand for U.S. Sen. John McCain (R).

In interviews with voters, education and health care continually come up as the biggest political priorities, rather than immigration, which tends to be most closely associated with Latino voters.

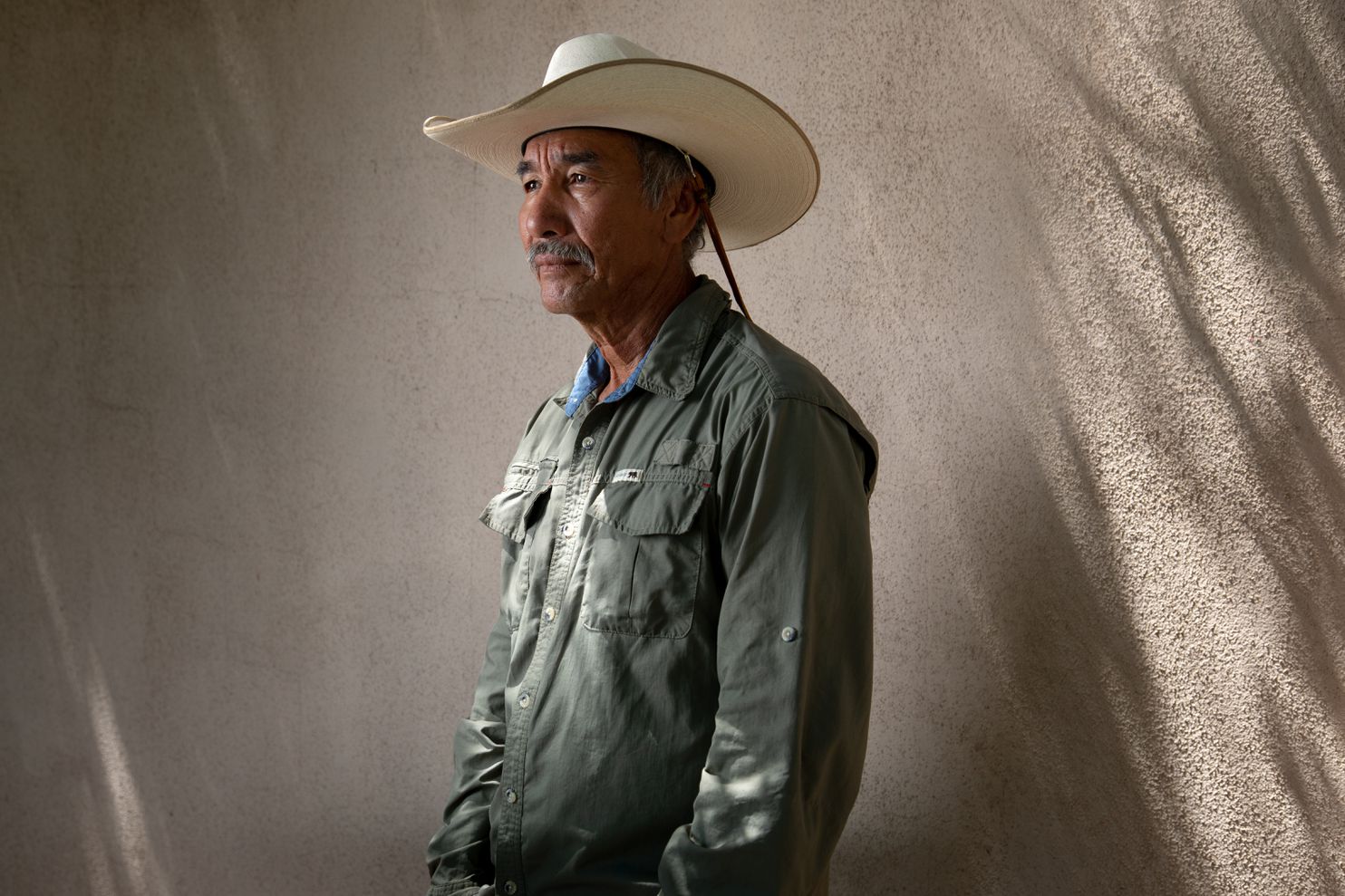

Pedro Ramos, 63, said he is conservative on social issues like same-sex marriage and abortion rights — a common refrain among religious Latinos — but nonetheless he has tended to vote for Democrats since he became a citizen in 1998. He said he supported McCain, who died in 2018, including when he ran for president against President Barack Obama in 2008.

Ramos, a maintenance worker at a private school and a landscaper, said he will definitely vote for Biden in November.

“This president is too crazy. He has ideas that are too crazy,” he said. “I think he has a tendency toward racism. His tweets are not just anti-Mexican, they are also anti-Brown people, anti-Jewish. I don’t like it.”

His son, also named Pedro Ramos, 22, strongly supports Trump. A recent poll by the New York Times and Siena College showed that an estimated 25 percent of Latino voters in Arizona are supporting Trump.

The younger Ramos said he does not see the president’s tough immigration rhetoric and policies as inherently racist. In fact, he agrees that the country needs tough border controls, even though his father was undocumented for a time. He noted that he receives much of his news from the conservative Daily Wire and raised questions about Biden’s age.

“The way he talks, I don’t think he’s mentally there. I think he’s kind of the last option for the left. I don’t like that they’re pro-abortion,” he said. “I don’t know who is coming through that border, I hate to say it. I’m pro wall in a way.”

He added: “I know being Hispanic that some people are going to say that’s shameful. But it’s what I believe.”

Many Latino voters, however, recoil at Trump’s rhetoric on immigration because they feel it crosses the line toward racism, carrying echoes to the debate in Arizona a decade ago over a law derided as the “show me your papers law.” Parts of the law, S.B. 1070, were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012, but resentment over that battle lingers.

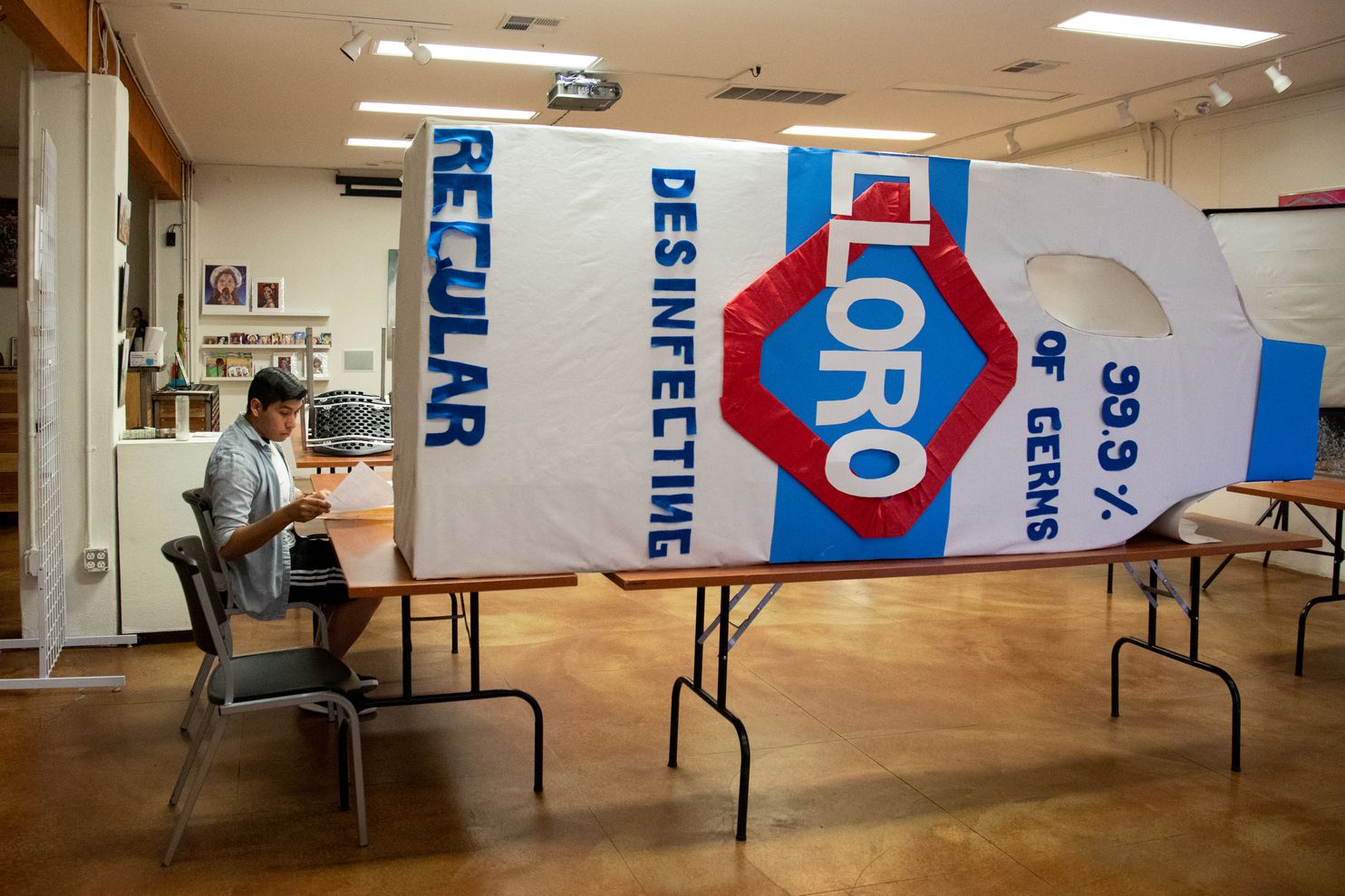

While the pandemic has emerged as one of Trump’s key political liabilities, it has also brought fresh organizing challenges to those trying to unseat him. It has stymied political canvassing efforts, which typically rely on person-to-person contact. That in turn has made it more difficult to engage the voters the party needs — especially young Latinos who have not registered to vote and are less likely to participate.

There are some workarounds built into the voter registration system in Arizona, said Lydia Guzman, the director of engagement at Chicanos Por La Causa. Already, 80 percent of Arizonans vote by mail. And eligible voters can register online.

Alexis Rodriguez, 20, who lives in South Phoenix, has been part of the effort to reimagine what it takes to engage voters without being able to canvass door-to-door or on college campuses.

“We’re trying to figure out how to do that digitally, which means lots of social media and phone banking,” said Rodriguez, a field program coordinator with Promise Arizona. “The transition has been hard but not impossible.”

They will need to reach voters like Vanessa Gonzalez, 40, an independent in Gilbert. Like others, she said her family history weighs heavily on her political views. Her grandfather, a Mexican national, moved from state to state picking cotton when he was young, before he started his own car dealership and became “the only Spanish-speaking car salesman in Chandler, Arizona.” She said that Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) really spoke to her as a candidate because of his emphasis on working families.

Gonzalez voted for Clinton in 2016, but she believes others did not take Trump’s chances of winning seriously and did not cast ballots. She said she intends to vote for Biden in November and will vote down the ticket for Democrats.

“He’s definitely not Bernie Sanders,” she said of Biden. “But I feel like, at this point, I just don’t want Donald Trump to win a second round at the presidency.”

She is extremely committed this cycle to making sure her friends and family cast ballots. She even sometimes looks online to see whether her friends are registered to vote, in case they are not.

Likewise, Biden was not Chavez’s first choice for the presidency, either. She had her heart set on Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and really wanted the Democratic nominee to be a woman. But she is used to making political compromises, she said, especially in Arizona. She is keen to see Trump voted out of office.

What Chavez wants is not politically radical. Better local schools. Affordable health care. Better paying jobs so parents do not have to work two jobs.

“I’m actually a little bit conservative, in some things. Nobody wants illegal immigration. But we don’t want children in cages, either,” said Chavez, a small-business owner.

Perhaps more than anything, she said, she wants to feel seen, to feel her community’s needs and aspirations matter to people in charge.

Several weeks ago she watched a speech Biden delivered, and she burst into tears.

“He was telling Trump off! It was beautiful,” she said.

Photo editing by Natalia Jimenez. Design by Tara McCarty. Copy editing by Sue Doyle.

Jose A. Del Real is a reporter on The Washington Post’s national political enterprise and investigations team. During the 2016 election, he traveled across the country to cover Donald Trump’s presidential campaign and filed stories from more than 40 states.