California, once a national role model for slowing the coronavirus’s spread, has seen record numbers of infections, hospitalizations and deaths in recent days. The surge follows the reopening of many higher-risk businesses, including beauty salons, restaurants, movie theaters and gyms.

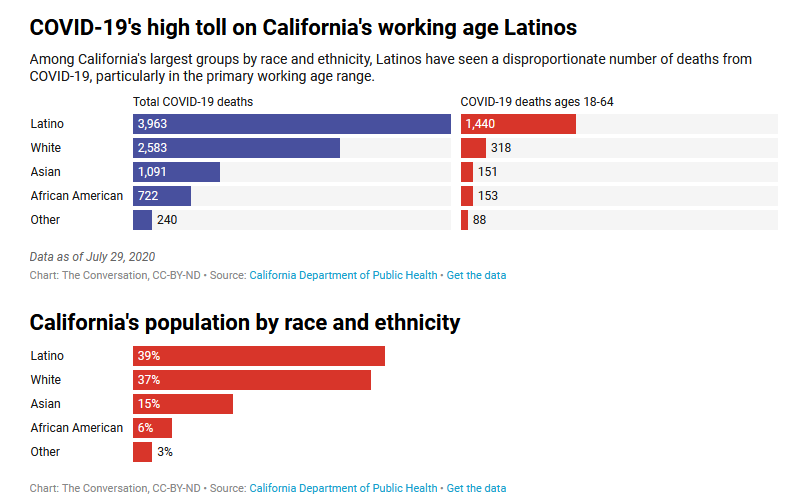

While everyone is at risk, low-income, Black and Latino Californians are dying at higher rates than high-income and non-Latino whites – and analyses suggest these gaps are widening.

In hard-hit Los Angeles County, a UCLA study released July 27 found Black and Latino residents were twice as likely to die of COVID-19 than non-Latino whites. In the poorest Los Angeles-area communities, county data shows the COVID-19 mortality rate was quadruple that of the wealthiest communities.

These health disparities are even wider when looking just at working-age Californians. While Latinos make up 39% of California’s population, they account for about 57% of COVID-19 cases and 46% of deaths. Among residents ages 18-64, Latinos account for 68% of the deaths.

As a medical sociologist in the Department of Social Medicine, Population and Public Health at the University of California, Riverside, I study how social factors such as income, race and ethnicity shape health. While California’s COVID-19 disparities are sobering, they are not surprising. They mirror decades of research showing marginalized Americans have worse health outcomes across a wide range of diseases. These health disparities are largely driven by unequal social conditions that shape people’s ability to avoid disease and get treatment.

What explains the state’s COVID-19 inequalities?

As cases of COVID-19 soar, differences in working and living conditions put low-income, Black and Latino Californians at greater risk of exposure.

Limiting face-to-face contact with others is key for preventing COVID-19, but for many low-income residents, social distancing and self-isolation are luxuries they can’t afford. Low-income, Black and Latino Californians are more likely to be essential workers and hold low-wage jobs that involve frequent contact with the public and require them to be at work sites where health and safety precautions are not always enforced. In San Francisco’s Mission District, for example, a University of California San Francisco study found that 95% of people testing positive for COVID-19 were Latino, and 90% of them could not work from home.

These groups are also more likely to continue to rely on public transportation during the pandemic and live in more crowded households, providing opportunities for the coronavirus to spread among family and community members.

COVID-19 testing shortages also affect these communities. Key to the safe reopening of California’s businesses was the promise of widespread testing and contact tracing. Reopening too quickly led to testing shortages, a surge in positive cases and a lack of resources to effectively trace infected people’s contacts. Many of California’s testing sites have a potential demand of 200,000 or more patients. Investigative reporting by ABC News and FiveThirtyEight has showed how residents in whiter and wealthier areas have greater access to testing centers and face less competition to secure scarce tests.

Higher rates of preexisting health conditions, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, also put low-income, Black and Latino Californians at increased risk of experiencing serious illness from COVID-19. Disparities in these preexisting conditions are related to long-standing barriers to accessing essential resources and a legacy of discrimination and racism. Lower rates of health insurance and other barriers to health care – including unequal treatment by health professionals – leave these groups at risk of foregoing or being denied critical COVID-19 care.

All of these factors allow COVID-19 to spread more rapidly across California’s lower-income, Black and Latino communities and have contributed to widening inequalities in mortality as overall cases surge.

What can be done?

The hard work Californians put in early in the pandemic to stay home and “flatten the curve” was undone in the weeks after businesses reopened and large numbers of people went back to gathering in indoor spaces. In parts of the state, hospitals are now overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. But much can be done to help reverse the infection trends.

Some of the most important steps are simple: By staying home when possible, wearing a mask when out and maintaining physical distance, Californians can help protect themselves and others from COVID-19. Staying home can also help lessen the demand for limited testing and treatment.

Testing is essential. For testing to be effective, everyone who is at high risk for infection, whether through daily exposure to the public at work or knowing they have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, needs access to testing and quick results so they can self-quarantine if necessary. California has launched targeted efforts to make tests available in the underserved communities most impacted by COVID-19. The data show these efforts are making progress but aren’t yet meeting the need.

Across the state, mandatory mask requirements and reclosing many businesses that had reopened should help slow disease transmission, provided the orders are followed. That will require public health, state and local authorities cooperating to enforce the rules.

Employers also have a responsibility to ensure adequate precautions are taken to prevent the coronavirus from spreading in workplaces. This can include providing paid sick time so employees can stay home if they’re ill and personal protective equipment for employees who come face to face with co-workers and the public.

Low-income workers in crowded housing often lack ways to self-isolate if they get COVID-19. Offering free temporary housing is one way to help them avoid transmitting the virus to others. Affordable alternatives to public transportation, such as reduced-cost rideshares, could also reduce disease transmission among vulnerable populations.

Finally, with hope of a vaccine on the horizon, ensuring equitable access to future COVID-19 vaccinations for California’s low-income, Black and Latino community members will be critical to avoid worsening these health inequalities.

Andrea N. Polonijo, PhD, MPH, is a Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Social Medicine, Population, & Public Health at the University of California, Riverside.