The LA Times Editorial Board

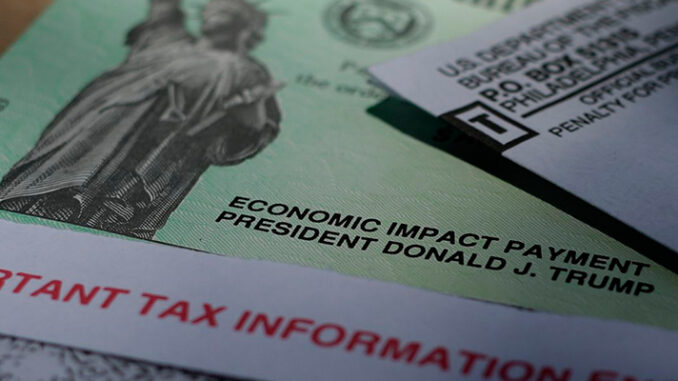

In the weeks since Congress passed the CARES Act — a $2-trillion stimulus package intended, among other things, to inject cash into a suddenly frozen economy — several organizations have filed lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of how the measure doled out individual stimulus checks. The legal challengers may have a point.

Under the terms of the act, checks of up to $1,200 per adult were promised to people whose annual incomes were at or below $99,000 and who had a Social Security number. Yet millions of people who work and pay taxes were left out. Why? Because they filed taxes using an Individual Tax Identification Number, which the Internal Revenue Service created for people who don’t qualify for a Social Security number but are legally obligated to pay income taxes — a duty that applies to anyone who makes money in the United States, regardless of immigration status.

The CARES Act also barred payments to anyone who filed a joint tax return with a spouse who used a taxpayer ID number, which has had significant consequences for U.S. citizens — denying stimulus money to their entire household, including the additional $500 payments for minor children who often are U.S. citizens too.

The nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute estimates about 1.8 million U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents are married to people living in the country without permission, and some 4 million children have at least one parent who does not have permission to live here. All told, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated that 4.3 million adults and 3.5 million children were disqualified from the stimulus program.

The Mexican American Legal Defense Fund, among other groups, argues in court filings that withholding checks from couples with mixed filing statuses violates the 5th Amendment guarantees of equal protection and due process. Whether that’s so is an issue for the courts to work out. But as a matter of fairness and effectiveness, limiting the payments to just those with Social Security numbers is hard to justify. It is patently unfair to deny stimulus payments to people simply because they filed taxes using a different — and legal — identifier instead of a Social Security number.

Shortly after the stimulus checks were announced, this page noted the unfairness of limiting payments to people with Social Security numbers. If the intent was to spur the economy, it made no sense to leave out taxpayers who are active buyers of goods and services simply because they didn’t file using a Social Security number. And before the immigration hard-liners start squawking about people living and working here without permission, many of those with the alternative numbers are here legally. They just don’t meet the criteria for joining Social Security. And while it’s true that many also are here illegally, the forefront issue is shoring up this consumer-based economy, and that requires spending — no matter the immigration status of the person doing the buying.

Congress created this problem, and it can — and should — fix it. The $3-trillion pandemic relief bill the House passed Friday would do so, while also teeing up a new round of stimulus payments. The Senate should get on board.

Unfortunately, both the federal and California Earned Income Tax Credits include a similar restriction — it’s available only to people who file taxes using Social Security numbers, not the individual tax numbers. Expanding that benefit at the federal level is highly unlikely, given the divisive debate over immigrants living and working here without permission. That’s unfortunate, especially since the restrictions often freeze out U.S. citizen dependents from the anti-poverty program.

But California and other states can write their own rules for eligibility for the earned income tax credit for state taxes. Expanding that to folks using the individual tax numbers was included in California’s last legislative budget, but it didn’t survive the final negotiations with the governor’s office even though the Franchise Tax Board estimated it would have cost the state only $60 million to $65 million each year through 2022.

The Legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom ought to work together to make that change. Yes, the state is in the midst of a pandemic-driven budget crisis, but expanding access to the EITC would be a smart and relatively inexpensive way to help low-income families who need even more help now than before, and whose contributions can help get California back on its feet.