Black Americans also more likely to be laid off or furloughed since economic shutdowns

by and , Washington Post

Blacks and Hispanics are also dying of covid-19 at higher rates than whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the seven weeks since states started issuing state-at-home orders, ADP Research Institute reported Wednesday that U.S. companies shed 20.2 million jobs from their payrolls in April alone.

Economists predict that the picture will grow even more dire Friday when the Department of Labor releases the first jobs report covering an entire month of shutdowns. Economists expect to see unemployment rates of 16 percent and record job losses of more than 20 million, said Heidi Shierholz, policy director at the Economic Policy Institute.

That’s a dramatic rise from last month’s report, which showed more than 700,000 jobs lost and the unemployment rate climbing from 3.5 percent to 4.4 percent. Hispanics suffered an especially sharp increase in the unemployment rate, from 4.4 percent to 6 percent.

Age and education also factor into the layoffs. The Post-Ipsos poll finds younger and blue-collar workers, as well as those without college degrees, are most likely to have lost their jobs.

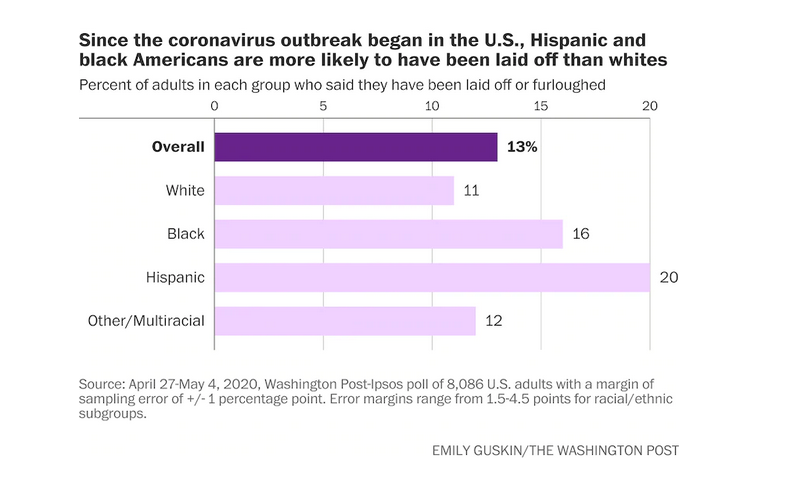

Hispanic men are hit the hardest — with 22 percent saying they’ve been laid off or furloughed. Among Hispanic women, 18 percent report being furloughed or laid off.

Robert Perez, a 33-year-old waiter in Victorville, Calif., was let go from his job in early March when the vegan restaurant where he had worked for six years closed. His girlfriend, with whom he shares an apartment, lost her job at the same restaurant.

The couple are looking for other work and weighing whether to apply for positions in an Amazon warehouse about 40 miles away — but they are worried about exposing themselves to the novel coronavirus.

“We have to consider it. We can’t just stay in the house and starve,” Perez said. “I watch the news. I wish things would reopen, but at the same time, if things open up now, everything is probably going to get worse. It’s going to come to a point where you’re going to have to go to work and take the risk.”

Perez had been making $40,000 a year working full-time. Now, he and his girlfriend receive a combined $1,000 every two weeks in unemployment benefits, half of which goes toward their $1,000-a-month rent.

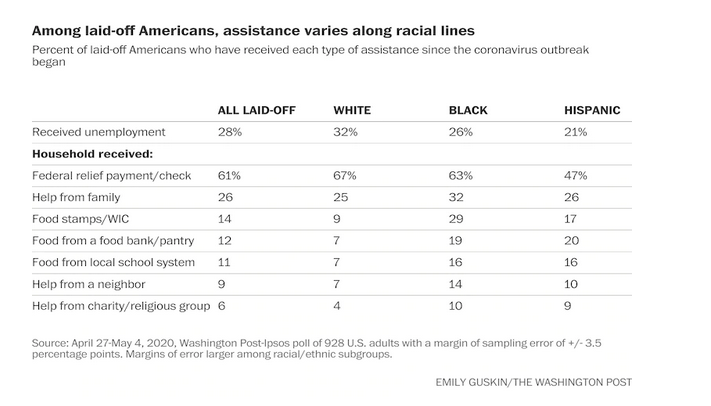

The Post-Ipsos survey of more than 8,000 adults and over 900 laid-off workers finds half of those who were laid off have applied for unemployment since March 1, with 28 percent of all those laid off saying they received benefits. Among those who did not receive benefits, 40 percent say they could not complete the application because phone lines were busy, they got disconnected or the website did not work.

Black and Hispanic workers are bearing the brunt of the economic crisis because they are overrepresented in industries that were hit first by social distancing mandates and stay-at-home orders, economists say. These include leisure and hospitality, such as hotels and restaurants; retail; and construction, where Latino men make up more than a quarter of workers.

“We still have a lot of occupational segregation in this country,” said Shierholz, chief economist to the secretary of labor during the Obama administration and an expert on wage inequality and unemployment. “Some of it is due to differences in educational attainment. Some of it is due to discrimination and people’s access to networks.”

The Post-Ipsos poll finds workers in blue-collar industries are more than twice as likely to report being laid off or furloughed as those in white-collar industries, 26 percent compared with 11 percent.

If historic ratios hold and if the overall unemployment rate rises to 16 percent on Friday, the black unemployment rate, which is typically double that of whites, can be expected to reach nearly 30 percent, Shierholz said; the Hispanic unemployment rate can be expected to hit 20 percent.

“All recessions exacerbate existing inequalities by race and ethnicity — and always hit black and Hispanic workers harder — but this one will be worse,” she said. “It will be an absolute nightmare.”

The devastating economic impact of the pandemic on communities of color clouds President Trump’s oft-repeated claims that he is to thank for previous record-low black unemployment numbers, a trend that had begun under President Barack Obama.

White families recovered from the Great Recession faster than black and Hispanic families, in part because white families hold much greater wealth to begin with, economists say. While net worth for all racial groups fell by about 30 percent during the recession, black and Hispanic families experienced an additional 20 percent decline between 2010 and 2013 at a time when wealth stabilized for white families, according to the Federal Reserve.

The disproportionate layoff rate among Hispanics is partially explained by citizenship status, the Post-Ipsos poll shows. Among Hispanics who are U.S. citizens, 15 percent report being laid off or furloughed, a rate similar to blacks. But among Hispanic noncitizens, which includes undocumented immigrants as well as green-card-holding permanent residents, 32 percent report being laid off or furloughed; they are also the most likely group to be left out of government assistance programs.

Among those who have been laid off, Hispanics are most likely to say the pandemic has been “a serious source of stress” and are twice as likely as whites to say their families will face “real financial trouble” in a month or less if nothing changes. But they are also the least likely group to have applied for or received unemployment benefits since March 1 or to have received a federal relief check.

“Our economic boom was fueled in part by the labor of Latinos, particularly Latino men in construction, and unfortunately those are the jobs that are gone in a recession,” said Orson Aguilar, director of economic policy at UnidosUS, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Laid-off black and Hispanic workers are more than twice as likely as whites to report receiving food from a local school system or food bank. Black households with a layoff are three times as likely as whites to say they received food stamps since the shutdowns began.

“The covid-19 pandemic exposed large gaps in the safety net for many workers, but black workers disproportionately so because of conditions that existed prior to the pandemic — a concentration of black workers into low-wage jobs and a lack of access to health care, employment, housing and other basic needs,” said Tanya Wallace-Gobern, executive director of the National Black Worker Center Project. “Black workers face a racialized political economy in which they are exploited because of their race and their class.”

The layoffs have hit America’s youngest workers particularly hard, with 20 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds reporting losing their jobs or being furloughed compared with 14 percent of those ages 30 to 64.

In Phoenix, A. Guzmán, a 23-year-old mechanical engineer, had just settled into her first job after graduating from Arizona State University, on track to making $68,000 a year and saving up for her first home. But four months in, she was laid off from her job at U-Haul. (Guzmán asked that her full name be withheld for privacy reasons.)

Before the coronavirus outbreak, Guzman had been looking for apartments, eager to move out of her parents’ home and start life with her 7-year-old son.

But she has a rare autoimmune disorder and grew increasingly anxious that she would contract the coronavirus by going into work. When she was the only employee to show up wearing a mask in April, a colleague told her to get away from him because he was afraid she would make him sick.

“I had a breakdown, and I wasn’t performing well,” Guzmán said. “I was terrified of getting sick.”

She said she greeted her layoff with a bit of relief because she no longer is required to go out. She and her son are living with her parents. Her father is also an engineer, now working reduced hours. Her mother is an elementary school teacher.

Guzmán tried applying for unemployment as soon as she was laid off but had to wait until she received her final paycheck to complete her application.

For now, she’s staying inside the house, where a stop sign on the front window alerts visitors of her weak immune system, and using the time to study for an engineering and training certification in hopes of landing a higher-paying job. Even as the Arizona governor begins to allow businesses to open, Guzmán does not intend to look for a job immediately and is worried about a surge in coronavirus cases.

“I don’t want the state to open too early because if a new wave hits and everyone is out and about, more people will start getting sick and we have to close again,” Guzmán said. “The economy shouldn’t be first. It should be safety.”

Other laid-off workers have already found new jobs — albeit at reduced hours or pay — with nearly a quarter reporting leaving home to work at least once in the past week.

In an Orlando suburb, a 44-year-old driver for Habitat for Humanity recently received a call back to work after being furloughed a month ago.

Previously, he had made nearly $33,000 a year working full-time, delivering building supplies and donations. The driver, who was preparing to pick up side jobs fixing cars with his brother, with whom he lives, said he’s hoping he will get at least 20 hours back but is grateful for whatever comes his way.

“It’s not going to be like before. It’s going to be very, very little hours, but it’s going to be work,” said the man, who has been in the driving business for 15 years and spoke on the condition of anonymity because he does not want to jeopardize his re-employment.

So on Monday, he will carry a bottle of hand sanitizer in his pocket, don gloves and a mask, and get behind the wheel.

The Washington Post-Ipsos poll was conducted April 27 through May 4 through Ipsos’s KnowledgePanel, a large online survey panel recruited through random sampling of U.S. households. Overall results in the Washington Post-Ipsos poll among the sample of 8,086 U.S. adults have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus one percentage point. The error margin is 3.5 among the sample of 928 people who were laid off.