by

America doesn’t have a plan to return to normal. The federal government’s failure to produce one could leave millions of workers, students and families stuck inside even after hospitals and first responders have weathered the initial crisis.

Reopening society, experts say, will require the regular testing of millions of people, a reliable and fast nationwide reporting network and an army of thousands of investigators tasked with tracking down those who may have been exposed to the virus. Experts have compared this to the effort to put a man on the moon and the Manhattan Project.

The federal government has yet to produce even the framework of a plan — let alone the supplies and workforce to carry it out — leaving states and local governments to cobble together their own tenuous roadmaps.

“It really does need to be started by the federal government,” said Gigi Gronvall, an immunology specialist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “It’s not something that you can just throw together. It should be worked on now while the tests are coming online and not weeks and weeks down the road.”

When the health emergency does abate, governors will face political pressure to loosen restrictions on business, travel and socializing. But experts say doing so without a widespread testing system only invites a second outbreak.

“The move toward less restrictive physical distancing could precipitate another period of acceleration in case counts,” reads a roadmap written by several public health experts, including former U.S. Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, which calls for “careful surveillance” before lockdowns are lifted. The report was published independently by the American Enterprise Institute, the right-leaning Washington, D.C., think tank where Gottlieb is a resident fellow.

The 16-page report drafted by Gottlieb and others is the most prominent plan for society’s return to normal. It calls for a “comprehensive national sentinel surveillance system.” But state officials say the U.S. government has proven inept, and they’re forging ahead with their own plans instead of waiting for its playbook. Whether those plans prove viable without real federal support is an unanswered question.

“With a strong federal presence, we could be so much further forward in terms of our public health response,” said San Francisco Assessor Carmen Chu, who serves on the task force planning the city’s recovery. “The lack of leadership at the federal level has hurt us. … We really can’t do it alone.”

Even if the health care crisis evaporated overnight, not one state currently has a sufficient testing and tracing system to begin easing restrictions, according to another report on testing from Gottlieb and others.

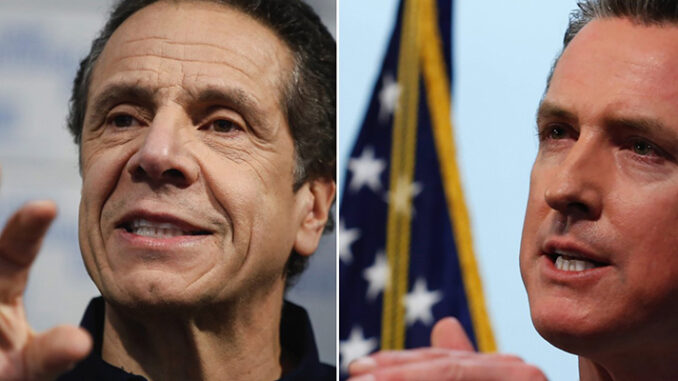

“[Reopening society] is going to come down to how good we are with testing,” New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, said in a news conference this week. “You have 19 million people in the state of New York. Just think of how many people you would need to be able to test and test quickly.”

Cuomo said ramping up testing to the necessary scale will be an enormous effort, and he’s working with the Democratic governors of New Jersey and Connecticut to coordinate a regional plan.

There’s no consensus on just how many tests will be needed nationwide to reopen the economy, but it’s clear the current system — which is generally only testing symptomatic patients who are high-risk or work on the front lines — is far from adequate.

James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve, said on “Face the Nation” that the solution is a universal testing system, an ambitious proposal that would require hundreds of millions of tests a day.

“What you want is every single person to get tested every day,” Bullard said. “And then they would wear a badge like they would after they voted or something like that to show that they’ve been tested. This would immediately sort out who’s been infected and who hasn’t been infected.”

Bullard did not respond to questions about how his proposal would be carried out.

States Go it Alone

Utah’s recovery effort is being overseen by Salt Lake Chamber President and CEO Derek Miller, who chairs the task force appointed by Gov. Gary Herbert, a Republican. The plan drafted by Miller’s team says that testing must become “mainstream” before most residents can return to work.

“In order to open up businesses, we need to get to a place where we can actually do testing on-site,” Miller said. “Opening up segments of our economy will necessitate a significant ramp-up of mobile testing, antibody testing and asymptomatic testing. We can’t flatten the curve, pat ourselves on the back and then risk a second wave.”

Utah is currently testing 3,000 to 4,000 people a day, Miller said, with plans to increase to 7,000. But any plan to begin rolling back Herbert’s “Stay Safe, Stay Home” order will have to include much more testing than that.

Utah has a population of 3 million, and some workers may need regular testing to ensure they haven’t caught the virus. As more testing is rolled out, restrictions likely will be pulled back gradually.

“I do see a phased approach to bringing segments of the economy fully back online by industry and by geography,” Miller said. Experts say it’s uncertain what free and clear will look like in deciding who’s ready to bypass social distancing and other precautions.

Other states are thinking ahead too. Cuomo has chosen a trio of business leaders to plan New York’s rebound. Cuomo’s office and planners did not respond to Stateline requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Florida Chamber of Commerce President Mark Wilson said in a release that his team is “already developing Florida’s statewide plan to restart our economy.” A month ago, March 11, just two days before President Donald Trump declared a national emergency, Wilson boasted that “Florida is open for business, for travel and for spring break.”

Wilson did not respond to questions about his role in state recovery planning.

A few plans already have been drafted. The Economic Research Organization at the University of Hawaii released a brief this month for restarting that state’s economy.

“The step that’s the most problematic is [developing] a well-defined system of testing, contact tracing and isolation,” said Sumner La Croix, a research fellow at the organization and one of the report’s authors. “Right now, we know very little about how that all proceeds at the state level.”

Hawaii has advantages, La Croix said, because of its geographical isolation, a relatively low number of cases so far and an already robust testing program. But officials will need to build a statewide system, perhaps by the end of the month, that brings public and private entities into a single testing regime.

“If we can work on that over the next few weeks and months, I think we might be able to open up our economy here faster than some other places,” he said. “We could have the surveillance testing in place to relax some of the stay-at-home orders we have.”

Unlike other states, Hawaii — which has nearly eliminated visitor arrivals to the islands — will be able to reopen without worrying that a surge of cases in a neighboring state might set back its own efforts.

Even robust testing might not be enough to return to normal. Health experts have called for an aggressive program of contact tracing to complement testing. Massachusetts is seeking to hire and train a team of 1,000 workers to attempt to track down every person who’s been in contact with a confirmed coronavirus patient and instruct them to self-quarantine.

Gottlieb’s report states that the contact tracing necessary to keep the virus in check when society reopens will require a substantial surge in the health care workforce. So far, Massachusetts is the only state seeking to conduct widespread contact tracing. A nationwide system at the same level would require nearly 50,000 workers.

A spokeswoman for GOP Gov. Charlie Baker, who has touted the plan, declined comment.

Utah’s Miller said the state is contacting about five people for every confirmed patient, a “manageable” number, but that the state may need to ramp up its contact tracing program if the caseload becomes overwhelming.

‘At Least We’ll Have More Information’

A pair of local governments are pioneering some of the first widespread testing programs — thanks to rare partnerships with local medical companies that have stepped forward — even as most states limit their tests to at-risk residents and symptomatic frontline workers.

Even those early successes show the limits of a patchwork system.

In Colorado’s San Miguel County, officials are partnering with a local company to offer testing to the county’s 8,000 residents. United Biomedical Inc. offered free blood tests to the county that detect antibodies, showing whether someone was exposed to the virus and had immunity.

Experts and officials think these tests, known as serology tests, could be crucial to putting some people back to work, as people with immunity could safely take on frontline duties. Germany is planning to issue “immunity certificates” that will allow those who have recovered to ignore lockdown rules.

Even as the Colorado county collects results, Gronvall, the immunology expert, said a strong nationwide program is crucial for immunity testing. Without a regulated system, there’s potential for employers to seek workers’ private medical information, and an incentive for people who want to go back to work to deliberately catch the virus.

“It’s definitely something that requires government attention, because of the potential for misuse,” she said.

About 6,000 San Miguel County residents have been tested so far, with most of the results still pending. Eight residents have tested positive.

“We don’t know how we’re going to use the information yet,” said Democratic County Commissioner Hilary Cooper. “We’re just waiting for the results and then at least we’ll have more information with which to make informed decisions.”

Without a more widespread testing system, San Miguel County doesn’t expect to reopen any sooner than its neighbors.

“We don’t live in a bubble, we live in a region surrounded by communities that we’re very dependent on,” Cooper said. “In order for this to be highly effective, we should do it in the entire region.”

Still, Cooper said the program could be instructive for other governments, noting that it took a “logistical miracle” just to organize testing in one small county. Although most county residents have been tested, results are slow to come in and a second round of testing was suspended, as the partner company’s New York laboratory is overwhelmed.

Meanwhile, the city of Carmel, Indiana, has begun testing all municipal employees for active infections. The Indianapolis suburb plans to test staff who interact with the public weekly, quarantining those who test positive. If the program proves successful, it could provide a model for how the workforce at large could get back to business with regular testing.

Of the nearly 400 tests that have been conducted so far, eight employees have tested positive, including several first responders.

“The people on the front lines, if we can determine who has it, we can keep them from spreading it and protect them and their families,” said GOP Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard. “The more people you can detect and isolate, the less spread there will be.”

Like San Miguel County, Carmel is partnering with a local medical company to offer the tests. Brainard said the testing is allowing city operations to retain some normalcy.

“We want to keep providing essential city services,” he said. “We have to make sure our sewers run, our water runs, the garbage gets picked up. Our employees generally need to have interaction with the public, even in this period of time.”

Within days, Carmel will test antibodies as well. Workers who are found to be immune will no longer be tested for active infections and will be able to donate blood to boost the immunity of others.

On Thursday, Brainard announced that Carmel would collaborate with local companies to donate 50,000 federally approved COVID-19 test kits to New York City.

Planning in the Dark

As states and cities make progress and continue their own planning, the lack of a federal plan has left many unknowns.

Experts and officials say even states that withstand the health care surge and create strong testing programs may find it dangerous to reopen if their neighbors fall behind, a consequence of the patchwork approach.

Rapid change has made planning difficult as well.

“One month from now, the types of testing ability we have may look very different,” said Chu, the San Francisco official.

Chu emphasized that the city will use an abundance of caution when deciding to reopen.

“We want to make sure we’re not going forward one step and falling back two steps,” she said.

Alex Brown covers environmental issues for Pew Trust’s Stateline.

.