by Michael Hiltzik, The LA Times

There’s no secret about why governors and state legislatures obsess over statistics on interstate migration.

Population changes point to economic strengths and weaknesses, at least indirectly. The loss or gain of a single mega-plutocrat can threaten to make a material difference in a state’s tax receipts. The flow of population into and out of states endows the winners with bragging rights and shrouds the losers with an aura of shame.

Migration is not necessarily determined by taxes.

In 2016, the relocation of billionaire hedge fund manager David Tepper from New Jersey to Florida prompted the former state’s officials to fret about the potential loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes. New Jersey had a top personal income tax rate of 8.97%; Florida has no income tax.

All this helps to explain the thirst for evidence of how the tax bill of December 2017, passed by a Republican Congress and signed by President Trump, could affect state and local budgets.

The most important provision of the bill, from the standpoint of state and local officials, is a $10,000 cap on deductions for state and local taxes, known as the SALT cap. The provision effectively raises the burden of state taxes on high-income taxpayers.

Anti-tax conservatives are optimistic that the cap could work as a political constraint on efforts to hike state tax rates on those in the “millionaire and billionaire” brackets.

The Wall Street Journal, for example, cited California’s “tax-the-rich boomerang” last October in trumpeting a Stanford University study finding a net outflow of wealthy taxpayers from the state after a 2012 tax hike. The Journal implied that the outflow was torrential; in fact, the actual figures showed that the migration was a trickle.

Ever since the SALT cap went into effect in 2018, the hunt has been on for signs that it has prompted more wealthy residents to move from high-tax to low-tax states.

“Despite some recent claims that it has,” Lucy Dadayan of the Tax Policy Center wrote on Feb. 10, “the data available support the view that ‘We don’t have any idea.’”

News articles crop up from time to time about things like surging purchaser interest in Florida condos from residents of New York or California. But they’re anecdotal, not data-driven. It’s hard to say whether the interest doesn’t reflect the pretax bill trend or bargains left over from a lengthy Florida real estate slump.

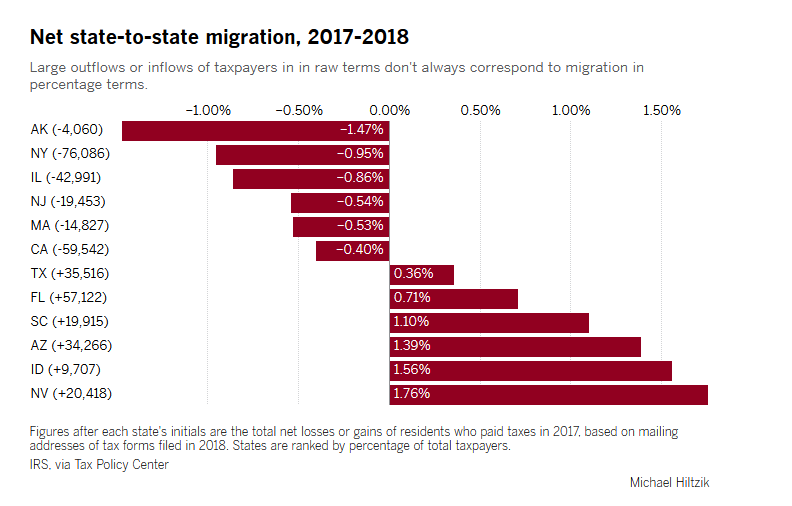

“Migration has been a problem for a number of years,” Dadayan told me. “SALT cap or not, New York has to be concerned about losing people.” Internal Revenue Service statistics show that New York lost more than 76,000 taxpayers from 2017 to 2018, nearly 1% of its taxpayers and the largest outflow among high-population states.

But as Dadayan observes, attributing that migration to concerns about high taxes in general or the SALT cap specifically is another matter. The third most popular destination for fleeing New Yorkers in recent years has been California, which has a higher top income tax rate; New York is California’s top source of inbound migrants. “Migration is not necessarily determined by taxes,” she says.

The SALT cap raised hackles in high-tax states. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo pronounced it “an economic civil war that helps red states at the expense of blue states.”

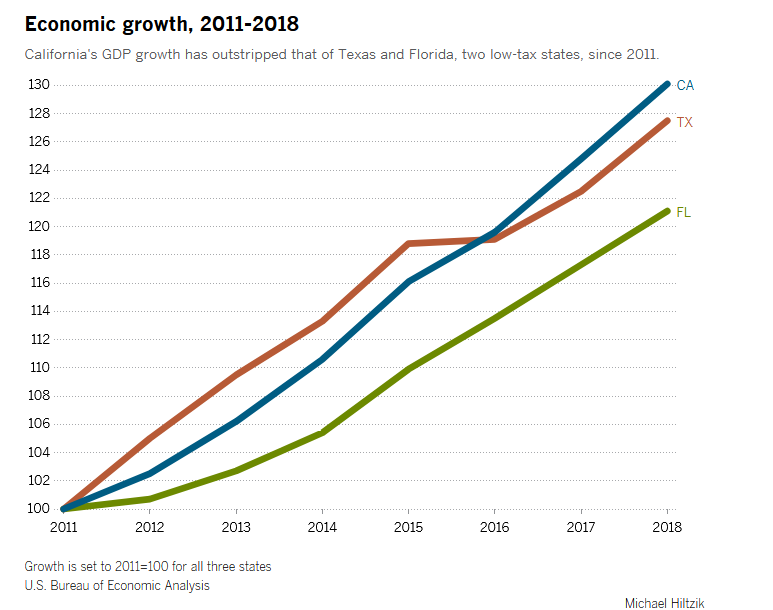

New York and California, among other states, tried to enact measures allowing taxpayers to circumvent the cap, but they were scrapped after the Internal Revenue Service ruled them out of order. In any event, tax revenues in California outpaced expectations in 2018-19, largely because of the state’s powerful economic growth.

It’s proper to keep a weather eye out for indications that taxes are causing disaffection among high-income taxpayers in California, chiefly because the state’s tax structure is highly dependent on the top brackets.

As the nonprofit news organization Calmatters reported in 2018, half of the state’s income tax revenues come from taxpayers earning $500,000 or more, and nearly 40% from those with incomes of more than $1 million. Those incomes tend to be composed more of capital gains than the average taxpayers’; they’re more closely linked to economic cycles — meaning that the next economic downturn could blow a hole in the state’s tax collections.

Evidence linking tax rates to the prospects for economic growth is sparse. As my colleague Margot Roosevelt reported last month, California’s job growth has outpaced the nation’s over the past year. In general, California’s economic growth has outpaced that of quintessentially low-tax states such as Florida and Texas since 2011, a period in which California raised taxes on the rich. Texas was the top destination of California migrants in 2017, according to the Census Bureau.

Pinpointing the relationship between the SALT cap and interstate migration is difficult for several reasons. One is that it’s too early to tell. The Internal Revenue Service has released taxpayer data only through the 2017 tax year; statistics for 2018 tax payments won’t be available until December.

The IRS bases its figures for interstate migration on the mailing addresses of tax forms; its latest figures are based on tax forms filed in 2018, but they apply to taxes paid in 2017 — before the tax cuts went into effect.

Several studies purporting to show the impact of the tax act used partial-year data produced by the Census Bureau, which isn’t considered to be as accurate as IRS figures. Since the tax act only went into effect in 2018 and people ponder at length a major life change such as relocation, Dadayan says, there’s simply too short a time frame and too sketchy a data set to determine any impact.

Moreover, year-by-year data are volatile, often for reasons that are hard to discern. California lost 59,542 taxpayer households in 2017-18, according to the IRS, but that was fewer than the 65,014 lost in 2016-17. In 2015-16, the state lost only 25,900, even though that was after the passage of the state’s “millionaires’ tax” via Proposition 30 in 2012.

Finally, information on interstate moves is extremely noisy because a multitude of factors go into a household’s decision to move. Taxes play a role, certainly, but so do job opportunities and lifestyle choices, family needs, health and the prospect of retirement. In recent years, California’s reputation as a high-tax state has been trumped by factors that may include its alluring weather, diversity and history of business creation.

Raw data can also be misleading, because big states generate big numbers on migration. Dadayan observes that while New York’s volume of net out-migration was the largest in the country, “the state with the largest out-migration rate as a share of total taxpayers was Alaska,” which has no personal income tax or general sales tax. Alaska lost more than 4,000 taxpayers in 2017-18, but they amounted to 1.47% of its taxpayers.

top income tax rates — Idaho (6.925%) and South Carolina (7%). California’s top rate, applying to income over $1 million, is 13.3%.

A good example of how things aren’t so simple came from Chipotle Mexican Grill, the fast-food company that recruited Brian Niccol from Irvine-based Taco Bell to be its new CEO in 2018.

Among the terms of Niccol’s deal was that the company would move its headquarters from Denver to Newport Beach, where he was living, even though California has higher property taxes than Colorado and nearly twice the per capita income tax burden.

The disparity is even greater for multimillion-dollar earners like Niccol. Colorado’s personal income tax is a flat 4.63% — in other words, for every million dollars Niccol earns after his first million a year, he’s paying $133,000 as a California resident but would pay only $46,300 in Colorado.

On the other hand, Niccol’s daily commute became even shorter than it was when he had to travel from Newport Beach to Irvine. And he didn’t have to relocate his three school-age children. These evidently were more important factors than taxes. (Of course, Niccol’s demand created problems for Chipotle’s 400 employees in its Denver and New York offices, which were closed.)

Among the nontax rationales for interstate moves, retirement, “family” and jobs tend to rank high, according to an annual survey by United Van Lines. Retirement was cited in last year’s survey by nearly 25% of Californians moving to other states, and only 11% of those moving into California. Indeed, the state experienced a net inflow of residents ages 18 to 54, but a net outflow of those 55 and older — that is, those nearing or already in retirement.

But in Arizona, where about twice as many people moved in as those leaving, retirement was the most frequently cited reason for in-migration. The state achieved a rough balance of inbound and outbound migrants for all age groups below 65. For those 65 and older, the balance tipped decisively in favor of newcomers.

Employment was often cited by departing Arizonans as their impetus for leaving. By contrast, jobs were by far the most-cited reason for people coming in to California, mentioned by nearly 60% of the newcomers.

The SALT cap may well bare its teeth, in time, restraining state and local policymakers from further tax increases and creating a flow of well-heeled economic migrants. But the signs of it haven’t appeared yet.