by

In recent years, an oil boom has pumped up the incomes of many rural residents in Texas, even as flooding and the trade war have dragged down incomes in Nebraska farm country. Both cases are emblematic of a broader trend: The counties with the most dramatic income gains and losses since 2016 are mostly rural and Republican.

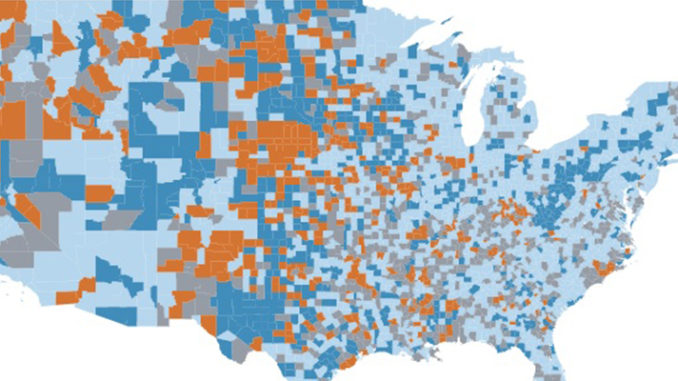

A Stateline analysis of Bureau of Economic Analysis data shows that while residents of booming big cities were most likely to have growing incomes in the three years between 2016 and 2018, rural residents had a very mixed outcome.

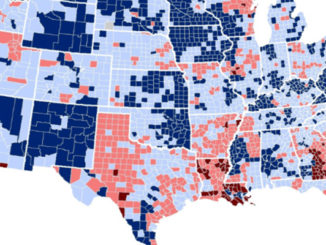

The numbers are yet another illustration of the urban-rural divide that characterized the 2016 election. Democratic-dominated metropolitan areas are thriving, attracting employers and highly educated and skilled workers who can earn big paychecks. Democrat Hillary Clinton won fewer than 500 of the nation’s 3,000 counties, but they accounted for nearly two-thirds of the nation’s GDP, according to an analysis by the Brookings Institution. Meanwhile, many residents of rural counties and smaller cities, most of which voted for Donald Trump, face diminished job prospects or depend on the ups and downs of energy and agriculture.

Nationally, the average personal income rose to about $54,000 last year, up 4% after inflation; and the typical county saw a 3% rise, whether it was Democratic or Republican, big city or rural. But in the list of the 200 biggest winners and losers, big Democratic cities tended to be among the success stories while rural Republican areas — which comprised nearly 90% of both lists — were split evenly between winners and losers.

Counties in West Texas, which benefited from an oil boom in the Permian Basin, dominated the list of those with the largest per capita income gains in that time, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data released in November. Only one of those counties voted Democratic: rural Reeves County.

Tops in the nation was Midland County, Texas, transformed by an oil boom that coincidentally had its biggest effect between 2016 and 2018, experts say. The county voted 75% for Trump in 2016, according to election data used in the Stateline analysis and maintained by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The average personal income in the county grew to $124,455, a 57% increase, and now ranks 10th in the nation, jumping ahead of wealthy places like Santa Clara in Silicon Valley and the hedge fund hub of Fairfield, Connecticut.

“We have been very blessed here by the oil and gas industry,” said Sherri Merket, the Republican Party chairwoman in Midland, “and the Republicans have been letting us do our job without putting too many regulations on us. Overall this area is going to stay very Republican.”

Rural Republican areas in one state — Nebraska — also dominated the list of biggest income losses. The top 10 drops in average personal income in the country, ranging from 21% in Banner County to 36% in Sioux County, were in that state.

That came from a perfect storm of floods, the trade wars, a weak ethanol market and a strong dollar that made it even harder to export farm products. Many of those trends also affected Iowa, Kansas and Minnesota.

Even if some of those ills can be attributed to federal policy, rural Nebraska voters aren’t likely to take it out on Trump or the Republican Party, said Deb Cottier, director of the Northwest Nebraska Development Corporation, an agency that advocates for economic growth.

“It’s kind of a ‘more cows than people’ situation in those agricultural areas,” Cottier said. “And Mother Nature has created a situation where it’s been very difficult to make a living from those cows. Trade issues have an effect on our local economy, but I don’t think people associate those problems with Trump or the Republican Party.”

Suffering in Nebraska’s agricultural counties may be even worse than it appears, said Ernest Goss, an economist at Creighton University in Omaha, because the per capita average glosses over the fact that some farm families made nothing because of flooding.

“The average disguises a lot of the pain that’s going on,” Goss said. In an attempt to stanch some of the economic damage, the Trump administration this year announced as much as $25 billion in new subsidies for agricultural areas.

The rural Republican pattern remains consistent for the top 200 counties in both income gains and losses. Almost 90% of counties that had large jumps or falls between 2016 and 2018 voted for Trump in 2016, and nearly 90% in both categories are rural.

But the cyclical surges in oil prices that lift West Texas from time to time don’t depend on which party is in power, noted Jesse Thompson, a business economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas who specializes in the Permian Basin economy. Even there, U.S. trade policies had mixed effects on the oil industry.

“There was a big windfall from the tax breaks and, on the other hand, some of these companies were hit by steel tariffs, because they have to pay a lot for the steel tubing they use,” Thompson said. “The price of oil is way more meaningful than either of those policies.”

The Midland area has been through times of layoffs and declining income. But in boom times, high oil profits draw West Texas workers away from other jobs, making it hard for other industries to find workers, he said.

“Midland goes through this every couple of years or so,” Thompson said. “There’s a tremendous surge in demand for workers at every skill level, from oil field hands to flipping burgers. It’s what happens when one industry sucks up all of the local resources.”

Similarly, the economy of Nebraska’s farm counties is tied to the rise and fall of agriculture.

It’s a pattern that extends to nearby parts of South Dakota, Kansas and other states with counties that depend on agriculture, said Nathan Kauffman, Omaha branch executive of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

“There were 31 counties in our state that saw a decline in income, and farm income constitutes a pretty high percentage of income in those counties,” Kauffman said. He emphasized, however, that the state has good economic prospects overall.

“The cities of Lincoln and Omaha account for by far the largest number of jobs and population, and they’re doing quite well,” Kauffman said. “There’s been a growing disparity between the urban and rural parts of our state.”

To be sure, the economies of some urban and Democratic counties changed dramatically. But the only big city where income dropped — by 2% to $55,747 — was Philadelphia. The top big city winners included the metro areas of Miami, Silicon Valley, Manhattan, Austin, San Francisco, Denver and Houston.

The county-level increases ranged from 9% in Miami and San Francisco to 19% in Denver.

All those urban counties, including Philadelphia, voted Democratic in 2016, except for the fast-growing Houston suburb of Montgomery County, which voted Republican.

States watch personal income closely because they use it to predict tax revenue and plan budgets. Statewide, Washington, Utah and Arizona had the biggest increases this year.

In the rural counties suffering from declining income, however, residents are unlikely to stop supporting the president, Cottier said.

“We are much more self-reliant than either coast or the urban areas,” Cottier said. “It takes a lot to raise the anger and ire of hardworking, rural, agricultural people. If they believe they are being treated fairly, they are not going to jump ship.”

Tim Henderson covers demographics for Pew Trust’s Stateline.