The front-runners for the presidential nomination are moving away from the charter school movement, and black and Latino families ask why their concerns are lost.

by Erica L. Green and

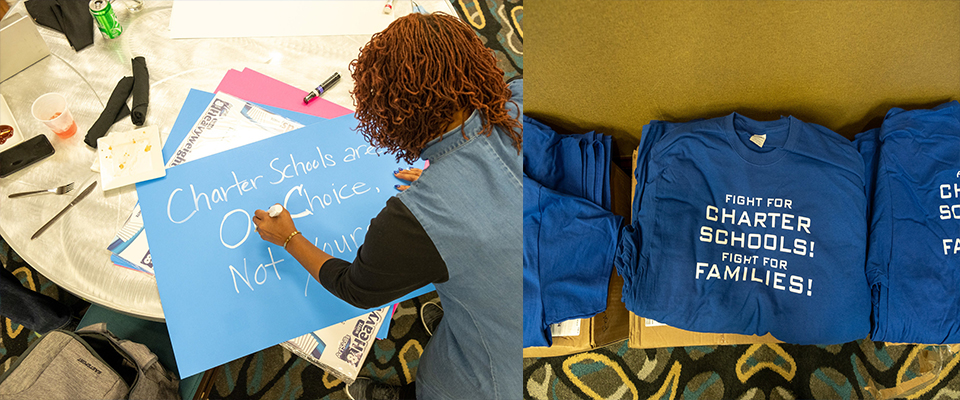

The night before Democratic presidential candidates took to a debate stage here last week, black and Latino charter school parents and supporters gathered in a bland hotel conference room nearby to make signs they hoped would get the politicians’ attention.

“Charter schools = self-determination,” one sign read. “Black Democrats want charters!” another blared.

At issue is the delicate politics of race and education. For more than two decades, Democrats have largely backed public charter schools as part of a compromise to deliver black and Latino families a way out of failing district schools. Charters were embraced as an alternative to the taxpayer-funded vouchers for private-school tuition supported by Republicans, who were using the issue to woo minority voters.

But this year, in a major shift, the leading Democratic candidates are backing away from charter schools, and siding with the teachers’ unions that oppose their expansion. And that has left some black and Latino families feeling betrayed.

“As a single mom with two jobs and five hustles, I’m just feeling kind of desperate,” said Sonia Tyler, who plans to enroll her children in a charter school slated to open next fall in a suburb of Atlanta. “They’re brilliant; they’re curious. It’s not fair. Why shouldn’t I have a choice?”

Charter schools, which educate over three million students, are publicly funded and privately managed — and often are not unionized. Nationally, the schools perform about the same as traditional neighborhood schools. But charter schools that serve mostly low-income children of color in large cities tend to excel academically. And bipartisan support in Washington has allowed charters to proliferate, with their waiting lists swelling into the hundreds of thousands.

Since Bill Clinton’s presidency, the charter school movement has had Democratic backing. It was central to President Barack Obama’s education legacy. But this campaign season, charter schools present a challenging issue for the four Democratic front-runners for the nomination, all of whom are white, in a nominating contest that will be heavily influenced by black voters.

Senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont, the two leading liberals, have vowed to curb charter school growth if elected. Former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., have raised questions about the role of charters and make no mention of the schools in their education platforms.

Each are chasing both the powerful endorsements of national teachers’ unions and the support of black Democrats who tend to be more supportive of charter schools than their white counterparts, according to polling.

In contrast, one of the black candidates in the race, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, is using his support for charter schools to distinguish himself, writing in The New York Times, “As Democrats, we can’t continue to fall into the trap of dismissing good ideas because they don’t fit into neat ideological boxes or don’t personally affect some of the louder, more privileged voices in the party.”

Groups like the Freedom Coalition for Charter Schools have spent the past few months setting up makeshift war rooms ahead of Democratic primary debates to pull Democrats back toward charter schools. And charter school educators are not afraid to raise the issue of race.

Richard Buery, the chief of policy at KIPP, the nation’s largest charter network, called the Democratic shift “a reflection more broadly of the lack of respect for black voters in the party.”

“These are folks that should be champions of black children and allies of black educators,” said Mr. Buery, a Democrat.

The Freedom Coalition for Charter Schools, started by Howard Fuller, a longtime school-choice activist and former Milwaukee schools superintendent, was formed in July after Mr. Sanders announced his plan. It gained momentum after Ms. Warren began signaling her skepticism of federal funding for charter schools.

Outside the Atlanta studio where the candidates were assembling for Wednesday’s debate, more than 300 people chanted “Our children, our choice” to the drumbeats of a marching band from a KIPP school. The next day, black and Latino charter school parents shouted the same refrain at Ms. Warren as she tried to start a speech about race in Atlanta. Representative Ayanna S. Pressley, Democrat of Massachusetts, who has endorsed Ms. Warren, pleaded with the protesters to let the candidate speak.

After the speech, Ms. Warren met with the protesters, concluding with a prayer and hugs. The candidate vowed to review her education plan to make sure she “got it right.” But the exchange ignited another controversy when Ms. Warren told an activist that her children had attended public schools. Her campaign clarified in a statement that although her daughter attended public school, her son completed the majority of his education in private school.

Some charter school supporters and donors have privately questioned the wisdom of confronting Democrats instead of focusing on ousting President Trump. Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, said the Democratic candidates were raising important questions about whether more charter schools were warranted. The candidates, she said, “looked at the evidence, which shows that charters are not a panacea for what people said they were started for.”

But Mr. Fuller — whose ties to major charter school donors like the Walton Family Foundation, financed from the fortunes of Walmart, has made him a lightning rod in the debate — said he was acting on parents’ sense of urgency.

“The establishment, run by white people, their strategy was, ‘Let’s be quiet and hope it goes away,’” he said in Atlanta. “We decided, no, we’re going to fight.”

Tariq Abdullah and his wife are planning to open a charter school in the Atlanta suburbs next year in part so their son can go to a school close to home without attending a failing school.

“We look at it as a burning ship going down with thousands of kids in it, and we’re trying to get kids on lifeboats,” Mr. Abdullah said.

Democratic misgivings with the charter school movement stem in part from its complexity.

Some charter schools are run by for-profit educational management companies and have been plagued by scandal. A few high-profile nonprofit charter schools have been accused of prioritizing high test scores over the needs of students with special needs. Other charters were created to serve children with disabilities, or to be more racially integrated than nearby district schools. Some states regulate their charter schools closely, while others have little regulation.

Ms. Warren and Mr. Sanders say their education plans would address the causes of educational inequality, in part, by significantly increasing funding for high-poverty schools.

Both plans echo the N.A.A.C.P., which called in 2016 for a moratorium on new charter schools. Mr. Sanders has gone further than Ms. Warren by linking charters to school segregation.

Josh Orton, a spokesman for Mr. Sanders, said the senator believed that “all students deserve a world-class public education, regardless of their ZIP code.” He added that “too many charter schools are unaccountable and contributing to privatization.”

Ms. Warren “wants every kid to get a great education regardless of where they live, which is why her plan makes a historic investment in our public schools,” said Saloni Sharma, a spokeswoman for the senator’s campaign. While her plan does not affect existing nonprofit charters, Ms. Sharma said, “she believes we should not put public dollars behind a further expansion of charters until they are subject to the same accountability requirements as public schools.”

The two senators’ education platforms call for a ban on for-profit charter schools, which represent a small fraction of the sector but have embarrassed other charters with a series of scandals.

Mr. Biden and Mr. Buttigieg have also said they want to curb the role of for-profit charter schools.

But Ms. Warren and Mr. Sanders appear likely to cut or kill the 25-year-old federal Charter Schools Program, created to jump-start new charters and funded at $440 million this fiscal year.

Margaret Fortune, the president and chief executive of Fortune School of Education, a nonprofit that operates seven charter schools in California, said the $2 million she has received from the program helped fund three schools.

“What would be happening in a fair society is we would be asked for our opinions, rather than having candidates saying, ‘I have a plan for you — to shepherd you into the very schools that you left on purpose,’” said Ms. Fortune, a black, lifelong Democrat.

The Democratic shift has already had consequences. Charter school growth was halted in New York City, home to some of the highest-performing charters in the country. Gov. Gavin Newsom of California, a Democrat, recently approved new restrictions and oversight over charter schools. Michigan’s new Democratic governor recently cut a $35 million spending increase for charter schools.

Since 2016, public polling has shown a widening divide on charter schools between white Democrats and their black and Latino peers. White Democrats’ approval of charter schools dropped to 27 percent from 43 percent between 2016 and 2018, according to a poll conducted by Education Next, a journal based at Harvard that is generally supportive of charters. Black and Latino approval for the schools remained basically steady at about 47 percent for each group.

Still, there is no consensus on charter schools among families of color. For example, charter schools have been polarizing in New York. More than 126,000 children are enrolled in the city’s mostly high-performing charter schools, about 10 percent of students in the country’s largest school district. But in neighborhoods with large concentrations of charters, some parents with children in district schools argue that charter school expansion has left their local schools saddled with more vulnerable children and fewer resources.

Max Lyttle, director of instruction at Eagle Academy Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., argued that pitting schools against one another misses the point.

“It shouldn’t be about what’s better: charter schools or neighborhood schools,” he said. “It should be about what schools will help our children succeed.”

At the school’s campus in southeast Washington, where more than 90 percent of students are black, Eagle Academy seeks to provide the same resources that white, affluent children have: a swimming pool, a chef who serves fruits and vegetables and a “sensory room” modeled on private medical facilities where students can calm down. The school was recognized this year for its improvements on standardized test scores.

On a recent morning, Ja’hari Dixon was asked if he knew what a charter school was. The student proclaimed, “Yes!”

“What is it?” Mr. Lyttle asked.

“A charter school,” Ja’hari said, “is a school.”

Erica L. Green is a correspondent in Washington covering education and education policy for the NY Times.

Eliza Shapiro covers education for the NY Times. @elizashapiro