by Alex Gonzalez

States don’t have the power to enact Immigration laws since the federal government has the power to set and administer immigration laws. However, It is clear to any rational person that America’s immigration system is broken and that the federal government’s response has been grossly lacking. As a result, some governors and state legislators in the past ten years have worked to fix what the federal government has refused to do due to partisan politics.

California is one of those states that has taken the leadership to pass laws addressing some of the most pressing issues for undocumented immigrants. The Pew Hispanic estimates that The Golden State is home to an estimated 2.2 million residents without legal status. Yet, admittedly, the state recognizes that these are workers, parents, and members of communities who pay taxes, like any citizen, and therefore, should have basic access the some of the state government agencies and basic legal protections.

The role of the states in immigration policy

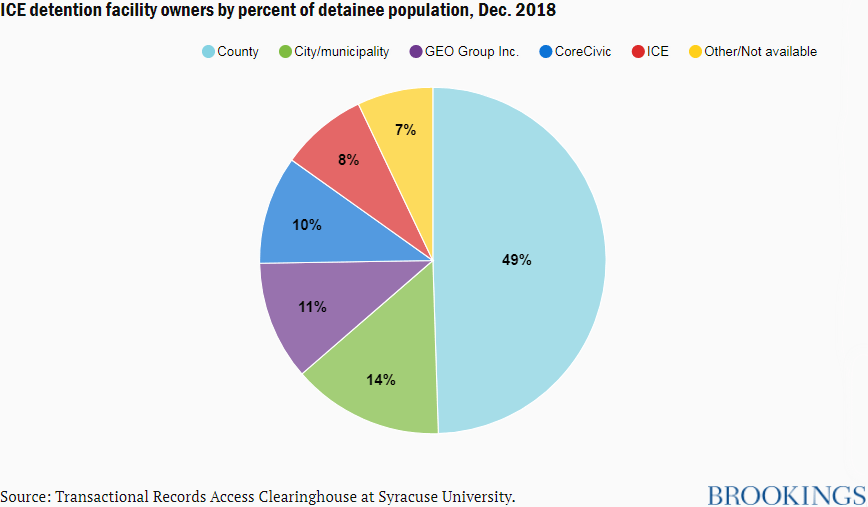

The idea that states could be in the driver’s seat when it comes to reforming our immigration system may seem counterintuitive. Immigration enforcement is a federal government power, and while some states and municipalities have opted not to assist federal authorities in immigration enforcement—most commonly referred to as sanctuary states or cities—the primary power rests with the central government to set and administer immigration laws. However, like many areas of policy, the issue has grown larger than the capacity of the federal government to address on its own. Therefore, the relevant federal agencies have used contracting to be able to administer the system.

Moreover, illegal border crossings into California are at their lowest level since 1971, and the state government doesn’t view its undocumented residents as a threat; California recognizes their basic humanity, and if you look at the labor market, immigrants are a big reason why California has such a dynamic economy. So why would California, or any other state for that matter, would want to protect its residents from outdated, and often harsh, retrograded immigration laws?

Last week, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that will end the use of private prisons and privately-run immigration detention facilities. Under the new law, California will phase out the use of these for-profit, private detention facilities by 2028. The state will be prohibited from renewing contracts or signing new contracts with a private prison company after January 1, 2020.

Both private facilities as well as county and municipal authorities are licensed and/or regulated by state governments. Those facilities are thus subject not only to the regulatory authority of the state, but state law enforcement, public health standards, etc. Other agencies also have jurisdiction to investigate and monitor these facilities. When an individual housed in one of these facilities—be that person a local-level offender or an ICE detainee—dies, is assaulted, is the victim of rape or other type of abuse, the state government has jurisdiction to investigate.

The state also believes that there some obligation by state to offer access to basic healthcare for those undocumented residents who cannot afford private insurance. Last July, California became the first state in the country to offer government-subsidized health benefits to young adults living in the U.S. illegally. The measure signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom extended coverage to low-income, undocumented adults ages 26 and younger for the state’s Medicaid program. Since 2016, California has allowed children under 18 to receive taxpayer-backed health care despite immigration status. And state officials expect that the plan will cover roughly 90,000 people.

The bill was introduced earlier this year and was initially proposed by Newsom as part of a larger health care package. It is expected to cover some 90,000 low-income residents between the ages of 19 and 25 and to cost the state $98 million in its initial year. The coverage would take effect in 2020, according to the legislation. In California, extending health benefits to undocumented immigrants is widely popular. A March survey conducted by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California found that almost two-thirds of state residents support providing coverage to young adults who are not legally authorized to live in the country.

Similarly, in October of 2017, former Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill SB 54 that placed sharp limits on how state and local law enforcement agencies can cooperate with federal immigration authorities. The bill banned state and local agencies, excluding the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, from enforcing “holds” on people in custody. The bill also blocks the deputization of police as immigration agents and bars state and local law enforcement agencies from inquiring into an individual’s immigration status.

Throughout the George W. Bush and Obama presidencies, programs like 287 (g) and Secure Communities were responsible for the detainment of millions immigrants with no criminal record in county and municipal jails. SB 54, like the new law Gov. Newsom signed a bill that will end the use of private prisons and privately-run immigration detention facilities, de-incentivizes county and municipal jails from being used as “detention beds” that they can rent to the federal government via “private prisons” and it discourages state and local law enforcement agencies from legally engaging in any Immigration Enforcement tactics.

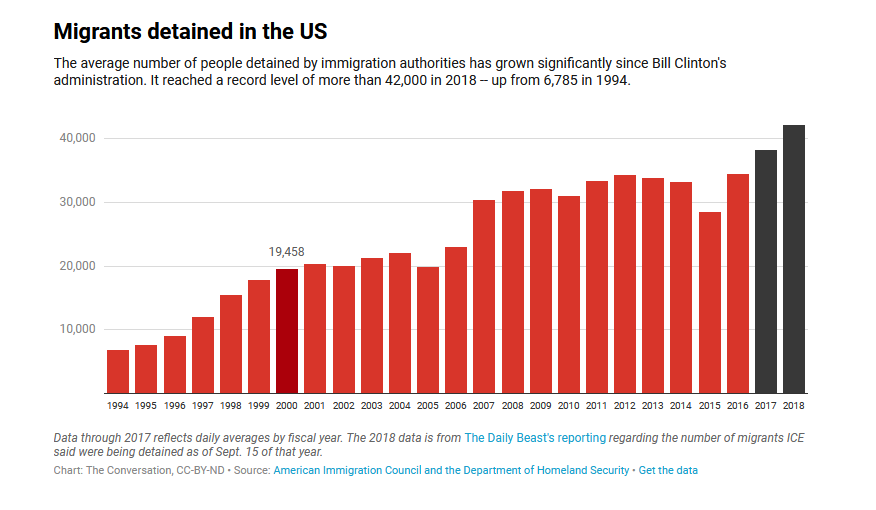

The 1996 law eroded due process for many migrants seeking asylum. It created a program that enlists local law enforcement agencies into immigration enforcement. Critics of the program say it drives a wedge between the police and immigrant communities, interfering with law enforcement.

Following the law’s passage, deportation numbers soared, setting new records for the numbers of immigrants detained during the Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama administrations.

California also recognized that undocumented residents work and that these workers must drive. On October 2013, Governor Jerry Brown signed a landmark bill After years of failed attempts, California became the tenth U.S. state that allowed unauthorized immigrants to apply for driver’s licenses. Governor Jerry Brown signed a landmark bill that kicked off in by January 2015. That was the first time in decades that unauthorized immigrants in California can obtain driver’s licenses. In 1993, a measure signed into law by Republican Gov. Pete Wilson required driver’s license applicants to provide a Social Security number and proof that their presence in the state was “authorized under federal law.”

The state estimated that about 1.5 million of residents were going to be eligible to apply for the new law. More than 1 million immigrants in California have been issued driver’s licenses since Assembly Bill AB 60 took effect in 2015.

The issue of “Dreamers” is also a very personal issue for California since more than half of Dreamers in the U.S. live in the state. The state cannot force Congress to pass the Dream Act. But what the state recognizes is that these are young Americans, and future taxpayers, that need to have access to adequate Higher Education.

In July, 2011, Gov. Jerry Brown announced signed the California Dream Act, a controversial bill that would allow undocumented students to receive public financial aid for higher education. The California Dream Act was divided into two bills, AB130 and AB131. AB130 was signed by Governor Jerry Brown on July 25, 2011, and AB131 was signed by Brown on October 8, 2011. AB 130 allows students who meet AB 540 criteria to apply for non-state funded scholarships for colleges and universities.

Understandably, Congress still needs to pass a comprehensive Immigration bill that can formally “legalize” the 2.2 million of undocumented residents in California. But what the state has done in the past ten years is admirable, it’s fixing the broken Immigration system than both parties, especially recalcitrant Republicans, in Congress have refused to address comprehensibly.

Alex Gonzalez is a political Analyst, Founder of Latino Public Policy Foundation (LPPF), and Political Director for Latinos Ready To Vote. Comments to [email protected] or @AlexGonzTXCA