by Kevin Mahnken

What happens to traditional school districts when charter schools come to town? Do they offer families new, high-quality educational options and help spread better teaching techniques? Or do they represent unwanted competition, swiping students and funding from districts until academic performance begins to suffer?

It’s a debate that divides much of the education community and is increasingly encroaching into politics and advocacy. School choice advocates point to signs that district schools see improvement in student test scores and attendance when charters open nearby. Critics cite research suggesting that the presence of charters leads districts to hemorrhage money. While politicians seem increasingly reluctant to touch the issue, educators have energetically defended both positions.

Now a new study finds striking evidence that the presence of charter schools in urban areas unmistakably boosts the average achievement of all black and Hispanic students, while not detracting from the achievement of white students. The phenomenon is particularly apparent in larger cities, though minority pupils are shown to selectively benefit from the presence of charters in rural school districts as well.

The study, released today by the reform-oriented Thomas B. Fordham Institute, is among the first to examine the question of how charter schools impact all students within a geographic area. While much research — in particular, a series of influential publications by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes — exists directly comparing the academic impact of charters versus traditional public schools, this one looks at how the performance of all students, in both district and charter schools, is affected as charter school enrollment grows.

While the study does not provide evidence for what is causing these effects — whether they originate entirely from what students are learning within charters, or additionally from how those schools are changing education throughout the school district — it does indicate that the spread of charters does not harm student performance in areas where they become more common.

That’s a standout conclusion given the state of the national conversation around school choice, which enjoyed a healthy measure of bipartisan support until recently. Now, both at the national level and in state capitals, some Democrats have campaigned to slow the rapid pace of charter school growth. A common argument to limit charter expansion holds that the publicly financed, privately managed schools hurt traditional public schools and the students they serve.

Fordham’s study relies on huge data sets from the Stanford Education Data Archive, a relatively new research tool that includes schooling information for over 13,000 geographic districts, including performance data for students in both charter and traditional schools. The archive uses federal NAEP data to facilitate direct comparisons between different state standardized tests.

“This is, in many ways, a triumph of big data,” Fordham researcher and study author David Griffith told The 74. “The Stanford data source…allowed us to compare across district lines when before, that was impossible. They’ve done all this groundwork to essentially put seven years of standardized tests on a common scale so that researchers can do this sort of thing.”

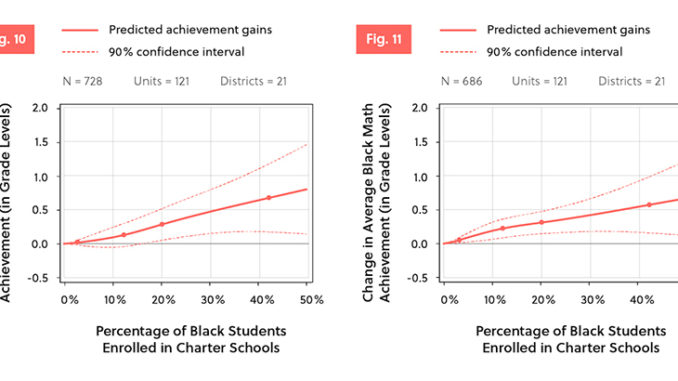

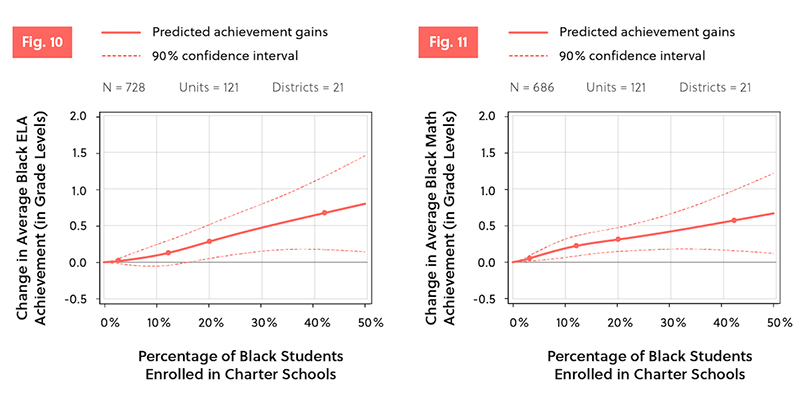

Griffith found that, as the percentage of black students enrolled in charter schools increased within an urban area, average English and math scores for all black students within that area — not just those enrolled in charters — increased substantially.

The effect was especially pronounced in the cities with the largest minority student populations. In the 21 urban districts that enrolled the most black students, moving from a 0 percent charter market share (i.e., charter schools enroll no black students) to a 50 percent share (i.e., charter schools enroll half of all black students in the area) led to sizable gains: 0.7 grade levels in math and 0.8 grade levels in English across the district.

In the 27 urban districts that enrolled the most Hispanic students, moving from a zero percent charter market share to a 35 percent charter market share (the threshold was set lower for this group because Hispanics students are less likely than black students to enroll in charters) was associated with a jump of 0.7 grade levels for all Hispanic students in both math and English.

Griffith underlined the particularly significant improvement in very large cities, a phenomenon that has been previously documented in other research around charters. Those urban areas, which boast large surpluses of human capital and are often marked by underperforming traditional public schools, maximized the promise of charter expansion, he argued.

“The bigger the city was, the more potential gains there were to be realized by increasing charter market share,” he said. “Places like New York and Chicago and Los Angeles, where there are a lot of really smart people who would potentially get into the education game under the right circumstances, are places where charters can potentially yield really dramatic, life-changing gains for minority students.”

At the same time, increased charter presence was not associated with academic gains for white students in urban, suburban, or rural areas. In fact, white students saw slightly negative impacts from growing charter market share in both cities and suburbs. That finding echoes earlier research from CREDO, which noted sizable learning losses for white students in a 2015 report on charter schools in 41 urban areas.

Disclosure: The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Doris & Donald Fisher Fund, the William E. Simon Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and The 74. The Walton Foundation was a primary funder of the charter study.

Kevin Mahnken was an editorial associate at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute from 2014 to 2016.