Is Trump’s rhetoric partially to blame?

by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux

The shooting in El Paso last weekend was one of the deadliest attacks against Latinos in recent memory. And in the aftermath, President Trump was blamed for encouraging the violence with his inflammatory anti-immigrant language, although he’s dismissed this criticism so far.

We will likely never know how much the El Paso shooter was influenced by rhetoric like Trump’s. But we do know that since Trump took office, surveys and studies have shown that Latinos, particularly Latino immigrants, have become more insecure and fearful about their place in the country.

And the El Paso shooting, which officials are treating as an act of terrorism, seems likely to reinforce and deepen these anxieties. The direct effect of a politician’s words is impossible to measure, but there’s evidence that in addition to creating a general sense of distress, Trump’s words may be fueling prejudice and aggressive behavior against Latinos and other minority groups.

Latinos feel more insecure than before 2016

In the wake of the El Paso shootings, many Latinos have said they are afraid for their safety. But George Escobar, the chief of programs and services at CASA de Maryland, an immigrant rights advocacy group, told me that this fear is just an escalation of concerns that are already common among the communities he works with. “Many people are afraid to go outside, to go to the grocery store — but we’ve been hearing similar fears for the past three years,” he said.

And overall, Latinos felt pessimistic and insecure about their place in the country well before the attack occurred. According to a Latino Decisions poll conducted in April, 51 percent of Latino registered voters think racism against Latinos and immigrants is a major problem (and 80 percent say it is at least somewhat of a problem). Meanwhile, as the chart below shows, a Pew Research Center survey conducted from July to September of 2018 found that nearly half of Hispanics say their situation has worsened over the past year, up from 32 percent soon after the 2016 election — a trend that began in the year or two before Trump was elected and has continued over his presidency.

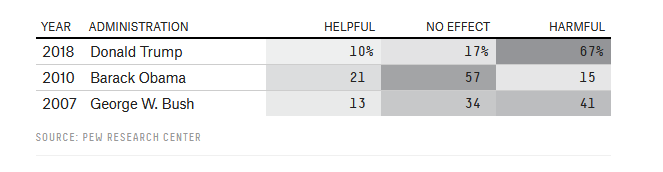

According to that Pew survey, more than half of Latinos agree that it has become more difficult to be a Hispanic person living in the U.S. in recent years. And overall, a higher share of Latinos say the Trump administration’s policies have been harmful to Hispanics, compared with the policies of either the Barack Obama or George W. Bush administration.

Most Latinos think Trump’s policies have been harmful

Share of Latinos who said the policies of the last three administrations were harmful, were helpful or had no effect on Latinos.

Thomas Kennedy, the political director of the Florida Immigrant Coalition, said that Trump’s rhetoric helps reinforce general fears of harassment and concerns Latinos already have about issues like deportation. That same Pew survey found, for instance, that immigrant Latinos were particularly concerned about their place in America; two-thirds, regardless of their own immigration or citizenship status, say that they are worried about the possibility of deportation. “The hostility from Trump is a constant thing that’s happening in the background,” he said. “It makes the threat hard to forget, and it heightens a sense of vulnerability, your fear that your community is being targeted.”

Kennedy and other advocates said that Trump’s language has also emboldened more people to engage in smaller acts of harassment or discrimination, like telling people to speak English or go back to their own country. The Pew study, similarly, found that four in 10 Latinos say they’ve experienced some form of discrimination in the past 12 months. And other research indicates that Trump’s presidency may even be taking a toll on Latinos’ health.

Trump’s rhetoric could be fueling broader hostility toward minority groups

It’s hard to untangle the precise impact of Trump’s rhetoric on this anxiety and hostility. Social scientists who study the link between speech and violence told me that determining whether a politician’s words directly caused an attack like the one in El Paso is a bit of an intractable problem. Susan Benesch, the executive director of the Dangerous Speech Project, a research group working on the links between inflammatory rhetoric and intergroup violence, told me that it’s not really possible to draw a direct line between anything someone hears or reads and a particular action. “Often the person who carried out the act doesn’t know exactly why they did something,” she said.

But there is evidence that particular kinds of rhetoric like Trump’s may spur prejudice and aggressive behavior, particularly among people who were already predisposed to hostility or extremism. For example, Nathan Kalmoe, a professor of political communication at Louisiana State University, found that exposure to mildly violent political metaphors increased support for political violence among people with aggressive personalities. And several other studies have also found that Trump’s rhetoric can increase prejudice against the groups he has targeted or make people more likely to express prejudice against those groups. These findings don’t indicate that this problem is widespread. (Other studies have actually found that white people, on average, say they’re less prejudiced now.) Instead, Trump may have encouraged people who were already prone to racism or aggression to say or do things they wouldn’t have before.

The way this works, several experts told me, is that inflammatory rhetoric can simultaneously dehumanize the groups it targets and paint them as a menacing force. Calling immigrants “invaders,” “thugs” or “animals” may encourage people who were already predisposed to aggressive or prejudiced behavior to see immigrants as a dangerous threat and make it easier to contemplate violence against them.

The nexus between Trump’s rhetoric and an act of violence is unusually clear in the case of the El Paso shooting, too. A screed allegedly written by the shooter echoed Trump’s frequent talk of an “invasion” of immigrants. And while the suspect did claim that he held these ideas before Trump entered the political scene, Kalmoe said that’s consistent with the way that political rhetoric can work in the world. Inflammatory language from the president might not persuade more people to adopt racist views, but it can make preexisting prejudices feel more urgent and pressing. “Racist rhetoric falsely alleging an invading subhuman horde signals an all-hands-on-deck emergency, demanding immediate action from people who already hate immigrants,” Kalmoe wrote in an email.

More research has suggested that Trump’s language may be at least partially fueling a broader rise in hate speech and hate crimes. One study found that hate crimes spiked dramatically after the 2016 election, to a level dwarfed only by the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, while another found that counties that hosted a Trump rally saw a significant increase in hate crimes. And other researchers found that Trump’s tweets about Islam-related topics were highly correlated with hate crimes against Muslims.

To be clear, the relationship between Trump’s rhetoric and hate crimes isn’t clear-cut, said Griffin Edwards, an economist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and a co-author of one of the studies. But, he added, “it’s very plausible that Trump’s language validated and encouraged a new wave of aggressive and violent behavior.” And all of these findings can help explain why Latino and immigrant communities are feeling insecure — and how Trump’s rhetoric might have been contributing, even before the El Paso shooting.

Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux is a senior writer for FiveThirtyEight. @ameliatd